- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Journalism

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Circles of Hell

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Here is what veteran war correspondent and Pulitzer Prize-winner Peter Arnett has to say about American political deliberation in the information age: ‘Government decisions are made by an inside group of Congress and the American public largely doesn’t give a damn. When they vote they don’t vote in terms of international policies; they vote in terms of local issues.’ New Zealand-born Arnett first worked in Vietnam for Associated Press, then in 1981 joined and subsequently became the voice and face of CNN. He has interviewed both Saddam Hussein and Osama bin Laden. How does he explain the US myopia he diagnoses? By looking at the news sources most Americans use: ‘They get talkback radio, which is skewed to the right usually; they look at a bit of television and maybe some magazine shows, and that is it. They don’t give a shit.’ But does he blame them? No. The controversial journalist (CNN, under pressure from government, dismissed him when he fronted a programme that accused the US of using sarin gas on American defectors in Laos) blames his own profession, or at least that part of the profession with corporate clout. ‘All this is the media’s fault. It is the newspapers’ fault for not including a page or two of international news every day so that people, like it or not, are going to see it.’ Nor does Amell spare the television networks: ‘CNN should be doing more, even though it has limited viewership; it should be doing more than covering celebrity stuff now, which it does domestically. Fox is a joke. There is an ignorance that is growing in America and it is frightening.’

- Book 1 Title: Traveller's Tales

- Book 1 Subtitle: Stories from the ABC's foreign coresspondents

- Book 1 Biblio: ABC Books, $24.95 pb, 263 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

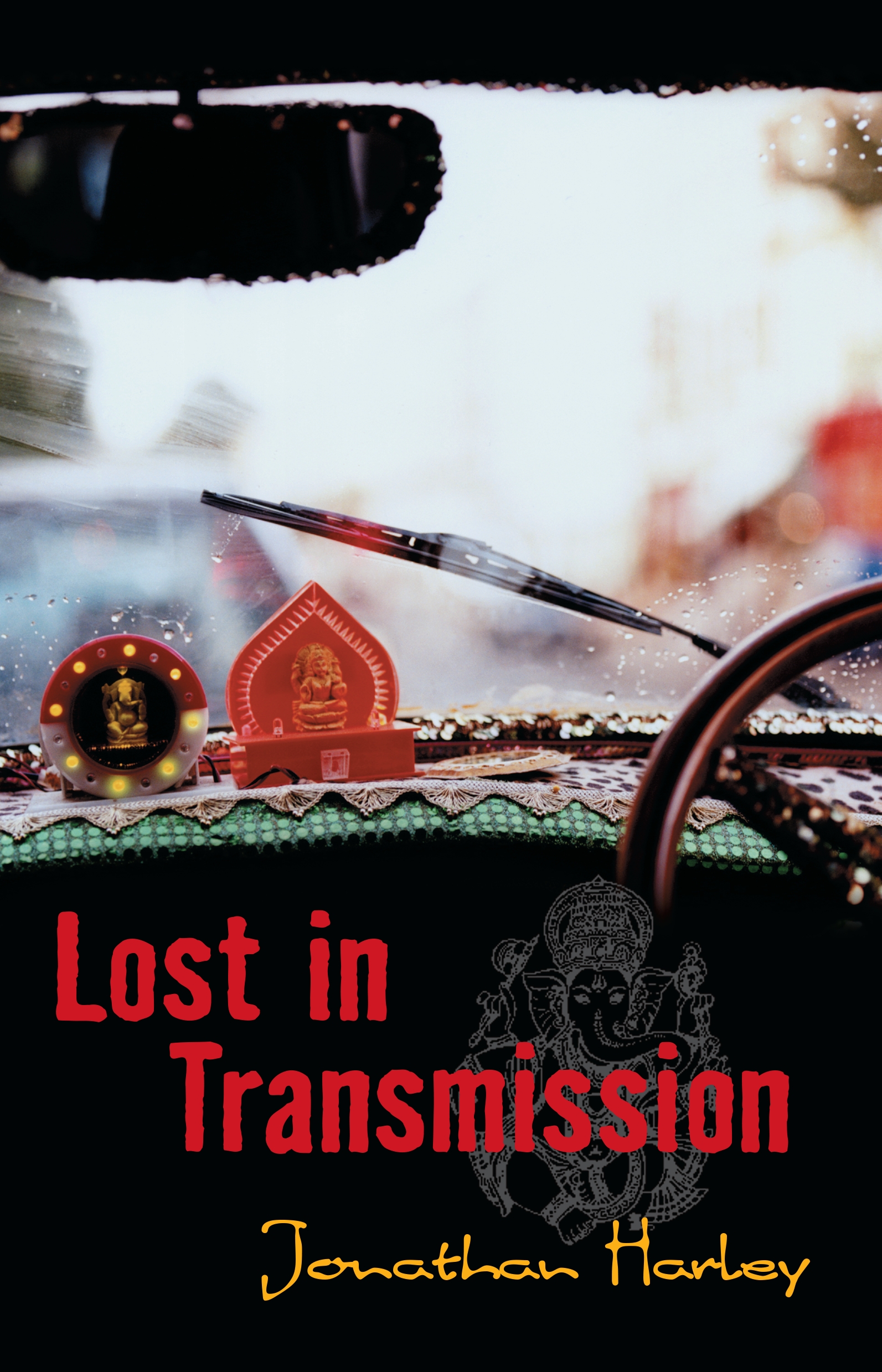

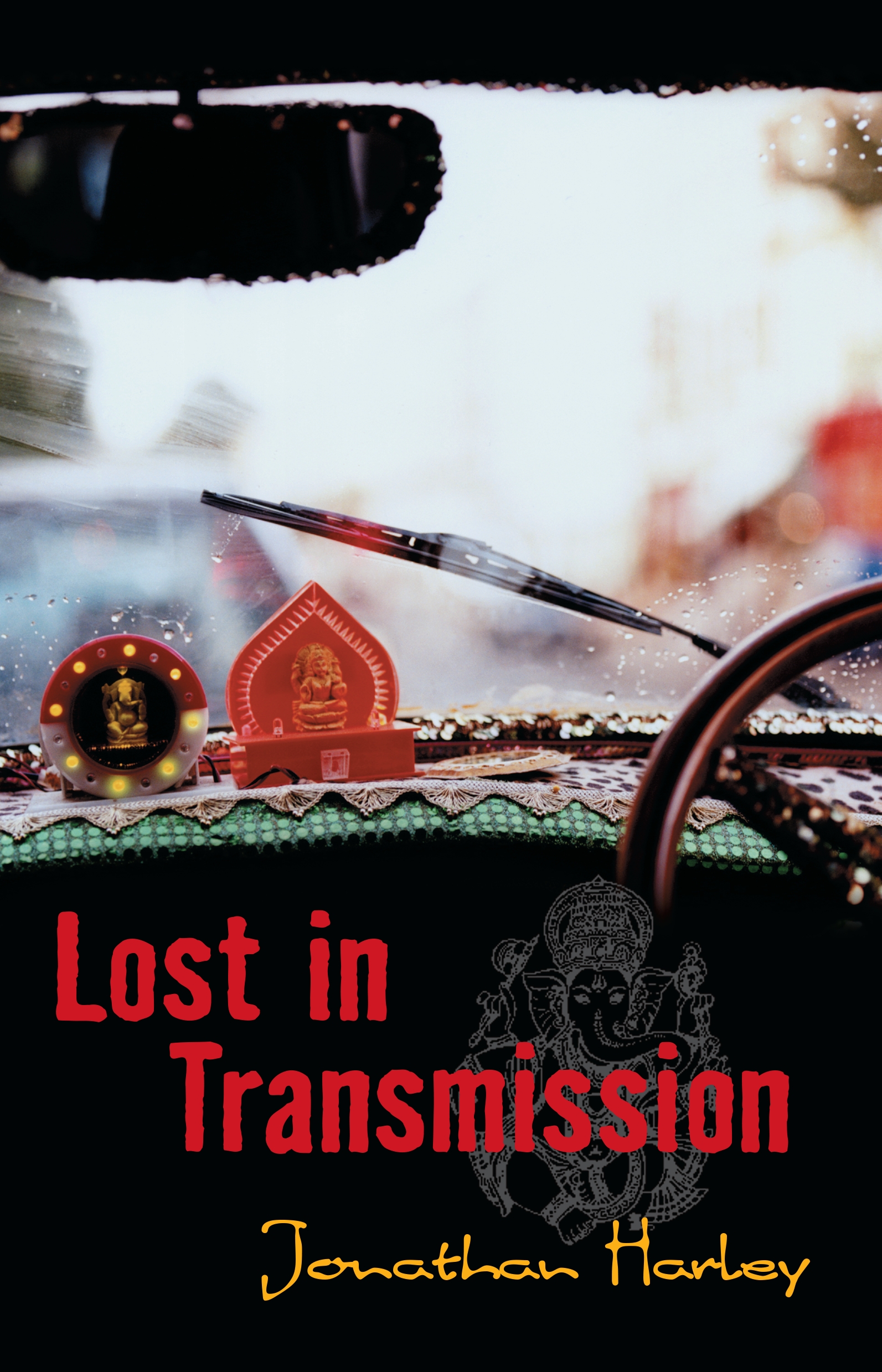

- Book 2 Title: Lost in Transmission

- Book 2 Biblio: Bantam, $22.95 pb, 352 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

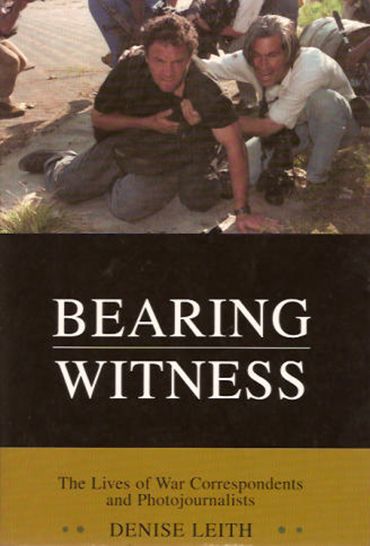

- Book 3 Title: Bearing Witness

- Book 3 Subtitle: The lives of war correspondents and photojournalists

- Book 3 Biblio: Random House, $32.95 pb, 402 pp

- Book 3 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 3 Cover (800 x 1200):

When a majority of Americans believe, in the face of all the evidence, that Saddam Hussein was implicated in the September 11 attacks, then, yes, it is frightening. And for journalists who risk their lives in an old-fashioned commitment to uncovering the truth, it must be not only frustrating but heartbreaking. So much information, so little discrimination, and even less understanding.

These three engaging books are in themselves an ironic symptom of the way the twenty-first century media world turns. Taken together, they provide more than just a vivid snapshot of the international politics of the last two decades: they are history lessons, morality tales. They explore, from the inside, sometimes with alarming honesty, the ethical quandaries journalists and photographers face. Do you take the photograph or stop the killing? Should journalists participate in human rights prosecutions? Is objectivity possible or even desirable? They illustrate, in often terrifying detail, how frontline news is gathered and disseminated, and do so with disarming candour: demonstration, not remonstration. They are an advertisement for the profession of journalism, and all the more effective for being sometimes modest or self-deprecating in an apparently guileless way. Many of the contributors write with flair; others are gifted talkers – classic Studs Terkell material.

But they are all here operating outside their normal professional routines. Much of this material has never found its way into newspapers or the nightly news. It is extra. Marvellous extra – you could teach a whole journalism course, or a history or politics or professional writing subject spring-boarding from these three books alone. But even if they become best sellers, they will still reach only a fraction of the mass media audience. So why, one has to ask, has this material not gone into feature pages in our national dailies already? Why, given the experience and talent manifest in these pages, are our newspapers full of syndicated international news?

Peter Arnett is one of nineteen interviewees in Denise Leith’s Bearing Witness, an exploration of the lives of war correspondents and photojournalists. These are professionals who work on the edge and pay the price. The cover photograph of Bearing Witness was taken during a gun battle, eleven days before South Africa’s first democratic election in 1994. Of the five photographers shown, two are now dead, one by suicide, and two carry gunshot wounds.

Leith explains that the book was prompted by two images that haunted her. One was American photographer Eddie Adams’s Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph of South Vietnamese police chief Nguyen Ngoc Loan executing a bound Vietcong prisoner in a Saigon street in 1968. The other also a Pulitzer Prize-winning image, by Kevin Carter was of a starving child in Sudan, with a vulture looming taken during the famine of 1993. Both photographs had extraordinary impact. Adams’s became the iconic anti-war image. Carter’s mobilised international aid. But both men knew another side. Adams believed that his photograph destroyed an honourable policeman’s life. Carter, who took the famine photograph but did not carry the dying child to a nearby feeding station, committed suicide soon after. The stories behind these photographs – not the ones the world knows – illustrate both the moral complexity and the extreme nature of the work.

Eddie Adams, who accompanied troops on 150 operations in Vietnam, is a natural talker and punctuates all romantic or heroic pretensions. In Vietnam, he formed a club called the TWAPs: Terrified Writers and Photographers. And he went there, he says, ‘because I thought the war was a big story. I didn’t say I was going to save the world.’ But the tough front doesn’t prevent the plain American from telling some truths that others might find challenging, even inspiring. Adams wouldn’t take the shot of a young marine paralysed by fear during Vietnam combat: ‘I remember it so vividly and I never took the picture. I know why ... This photograph would have told the whole story of the war but it would have destroyed his life for being a coward. I knew that he wasn’t a coward. I knew that my face looked exactly like his.’

Robert Fisk, talking about reporting from the Middle East, and Monica Attard from Russia, reveal different but related ‘rules of behaviour’. For Attard, the imperative is to ‘keep the microphone running, talk with as many people as you can but let them tell their stories and don’t provoke - more than anything don’t provoke’. Ego, says Attard, is what makes journalists provoke. Fisk, not devoid of ego, gives a fascinating interview, the fascination inhering partly in what he reveals about himself, but more – much more – in what he tells about events on his patch. Fisk has lived in Beirut for decades, and his experience is clearly crucial. His recounting of his insistent investigation of the Sabra and Chatila massacres is the exemplary practice of the theory expressed by another contributor, New York correspondent David Rieff. Rieff believes that ‘writers and photographers should be as unconstructive as possible, I don’t think that we should become servants of our hopes either. We are there to be critical, to tell the truth insofar as one can know it.’

Hard-bitten Rieff may be, in ‘a world that is largely a slaughterhouse’; he serves also as spokesman for all the contributors to this international volume when he concedes that: ‘You get to try your hand, however unsatisfactorily, at telling a piece of the truth. What could be a bigger privilege? That’s worth dying for.’

The twenty-two Australian ABC foreign correspondents whose stories make up Travellers’ Tales would, I believe, concur. As would the helter-skelter Jonathan Harley whose Lost in Translation is a serious delight of a book, profound, sensitive and realistic about himself, about the India he finds himself in – ‘the richest, poorest, most charming, infuriating, beautiful and hideous land in the history of time’ – and the Afghanistan he comes to cherish: ‘a tragic and magic land that has tested and tantalised every pore in my body.’

Both books are testimony, I’d hazard, to a particular finesse that Australian bring to the business of writing about other countries. Perhaps the openness that seems characteristic of their reportage comes out of a curiosity that is stronger than any stylistic or national carapace. Whatever its source, it makes for enlightening reading: Evan Williams on Gus Dur and Hun Sen, indelible moments of record; Michael Brissenden in Berlin, wearing his erudition so lightly while conveying the complexity of German unification; Michael Maher tracing Graham Greene through the length and breadth of Vietnam with a multi focal lens, merging past and present.

Next time you feel like consigning journalists to a circle of hell somewhere below politicians and adjacent to car salesman, you might take up any one of these three books and ponder the great resource we have in serious foreign correspondents. Cause for celebration, not vilification.

Comments powered by CComment