- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Thick or Thin

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The end of the Cold War in 1991 sparked a great debate about the fate of the international order and, in particular, of the so-called Westphalian system in which nation-states were the main actors. Since the end of the bloody Wars of Religion in 1648, there has been, in short, a sort of understanding that the international system should concern itself with wars between states, not wars within states. The problem is, however, that many conflicts today belong in the second category. In its endeavours to keep the peace, the international community has to adjust to this reality. The question is how.

- Book 1 Title: Understanding Peacekeeping

- Book 1 Biblio: Polity, $69.30 pb, 342 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

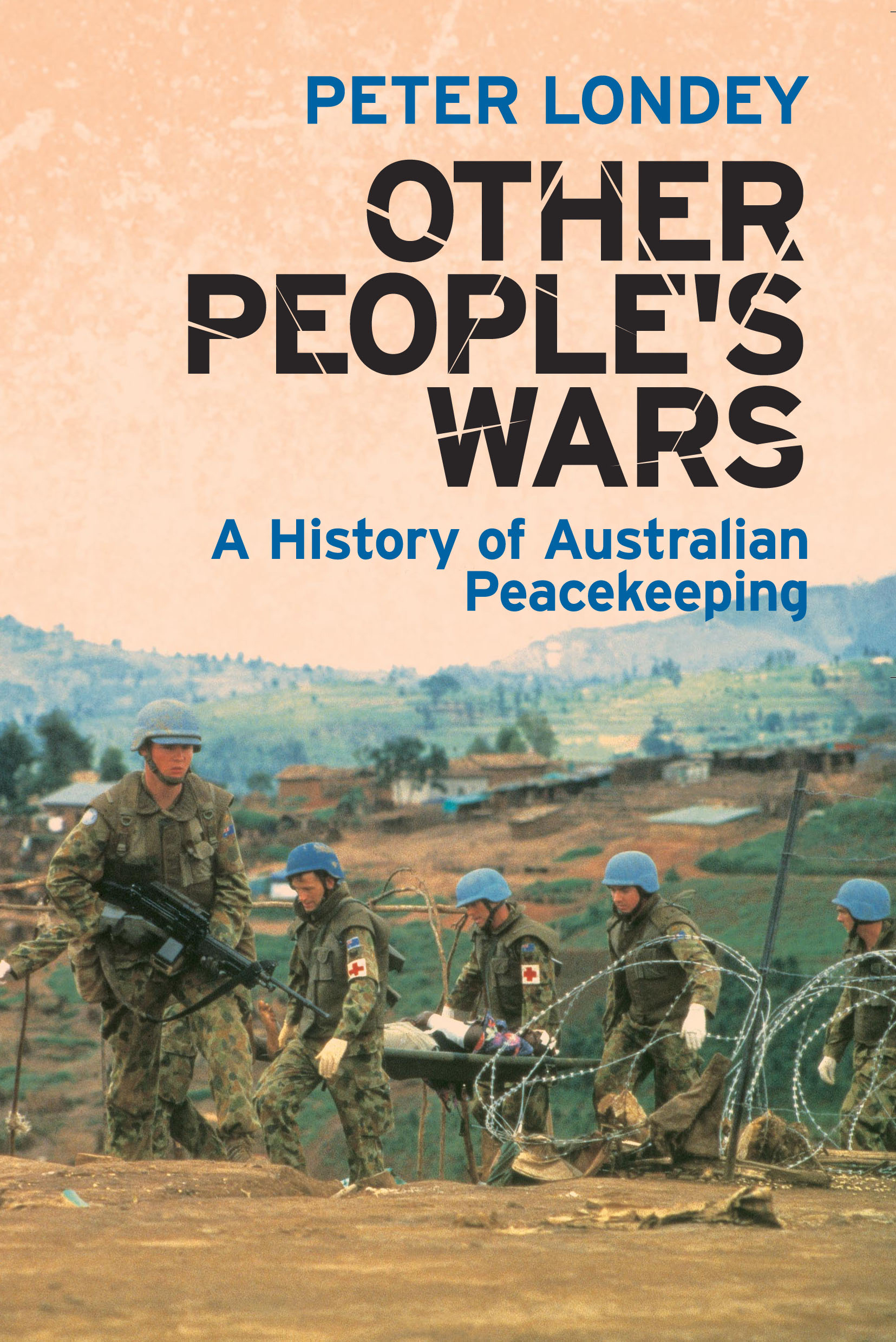

- Book 2 Title: Other People's Wars

- Book 2 Subtitle: A history of Australia's peacekeeping

- Book 2 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $35 pb, 334 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

The authors argue that the many players in peacekeeping – non-government organisations, international finance institutions, regional bodies, as well as security forces (some of which today, arc contracted privately) – will be assembled according to the level of need. The UN, however, has not been successful in ‘thick prevention’ strategies – those designed to transform societies by dealing with the major underlying social and economic causes of conflict. It has, rather, been concerned with ‘thin prevention’ strategies, such as providing mediators or deploying lightly armed peacekeepers. Arguably, these strategies fell well short of the mark when the UN sought to address the problems in Africa and in the Balkans during the 1990s. The response, therefore, has been for other players to intervene in the business of peacekeeping. The tragic situation in Bosnia and Kosovo required the hefty resources of NATO, while the intervention in Timor was subcontracted to Australia at the head of a large ‘coalition of the willing’. The message is that peacekeeping has become urgent and the UN will have to share the role. That, in part, became almost inevitable after September 11.

Peter Londey is not as exercised by the conflicting issues of peacekeeping. His intention is simply to narrate the history of Australia’s role in this practice, especially given our increasing profile since the Timor intervention in 1999. For all the emphasis in military history on alliance warfare – Gallipoli, the Western Desert Vietnam and Iraq – ‘the story of Australia’s military engagement with the world since 1945 is, above all, the story of peacekeeping’. Since that time, writes Londey, Australia has participated in almost fifty peacekeeping operations – most without fanfare. To be sure, many were tiny missions: thirty police were sent to Haiti in 1995; one military observer was sent to Guatemala in 1997. The trend after the Cold War, however, has been to significantly expand the role and corresponding size of peacekeeping forces.

There has been a move, in the wake of the Bosnian disaster, from peace-monitoring to a more robust peace-enforcement role. At the same time, the size of deployments has increased. The Australian contribution to the Timor force – Interfet – was 5000. Major military forces and civilian support staff were sent to both Somalia and to the Solomon Islands. Not only are the missions larger, but they now cover a host of activities associated with ‘thick prevention’ strategies, which the Australian Defence White Paper of 2000 describes as ‘military operations other than war’. The peacekeepers themselves have come to include many different crafts: medicinal, police, engineers, teachers and traditional security forces.

Londcy also reminds us that peacekeeping is not the monopoly of the UN. Indeed, in Australia’s case, a significant number of missions have been conducted with no desire to include the international body. The first major postwar mission, a battalion to the British Commonwealth Occupation Force in Japan, was an empire exercise. Ben Chifley, for his part, saw UN peacekeeping as a ‘drain on limited manpower’ that was to be accorded a low priority – something that will draw a response from the strong school of Labor internationalists. Less surprising is the Australian commitment to the Sinai, a US-sponsored initiative that failed to get UN support. In a similar vein, Bob Hawke was quick to shore up his pro-US credentials when precipitately offering forces in the first Gulf War. John Howard has taken this rather further.

The examples would seem to point to the centrality of the US bilateral relationship in determining the character of much Australian peacekeeping. But Londey argues that it really came down to who had the foreign affairs portfolio at the time. Bill Hayden was a realist and not inclined to emphasise Australian multilateral commitments, while Gareth Evans was an internationalist ‘in the Evatt mould’.

A particular feature of Londey’s work is that he gets close to quite a number of the peacekeepers themselves. In the early days, professionalism was not always a feature of Australian missions: Major Smith calling his hosts ‘dirty Dutch dogs’ while on tour in the Netherlands East Indies in 1949; Major Blumer, the commander of D company in Somalia, more than forty years later, acted like the US marines in kicking the ‘Somali Butt’. As peacekeepers generally, concludes Londey, Australians have gained respect for their efficiency but can fail to make due allowance for people from different cultures (something to do with our laconic humour and the accent).

Both books take it as a certainty that globalisation has set the context in dramatic ways for peacekeeping – or, rather, for more robust peace enforcement. As the Australian defence budget approaches $15 billion – up from $9 billion in 1999, as the Timor deployment was being organised – it is clear that Australian participation in such operations will assume growing priority. Less clear is the relative role of the UN, as opposed to the US, in determining such involvement. The authors do not claim here to answer the problems caused by the unilateral US action in Iraq, but they have materially set out the issues for those interested in tracing the nature of international security after the Cold War.

Comments powered by CComment