- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Landscape as Subject

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘Wildflowering’, a term coined by Judith Wright, describes the activity of searching for wildflowers in the bush. In letters between the poet and her friend, wildflower artist, writer and activist Kathleen McArthur (1915-2001), ‘the language of flowers’ becomes part of the mutual exchange of their friendship and epitomises the interactive and intimate relationship they maintained with landscape. Over the years, these women took the knowledge and love of their places into political campaigns to preserve the fragile ecology of an ancient coastland against the ravages of development and commercial exploitation.

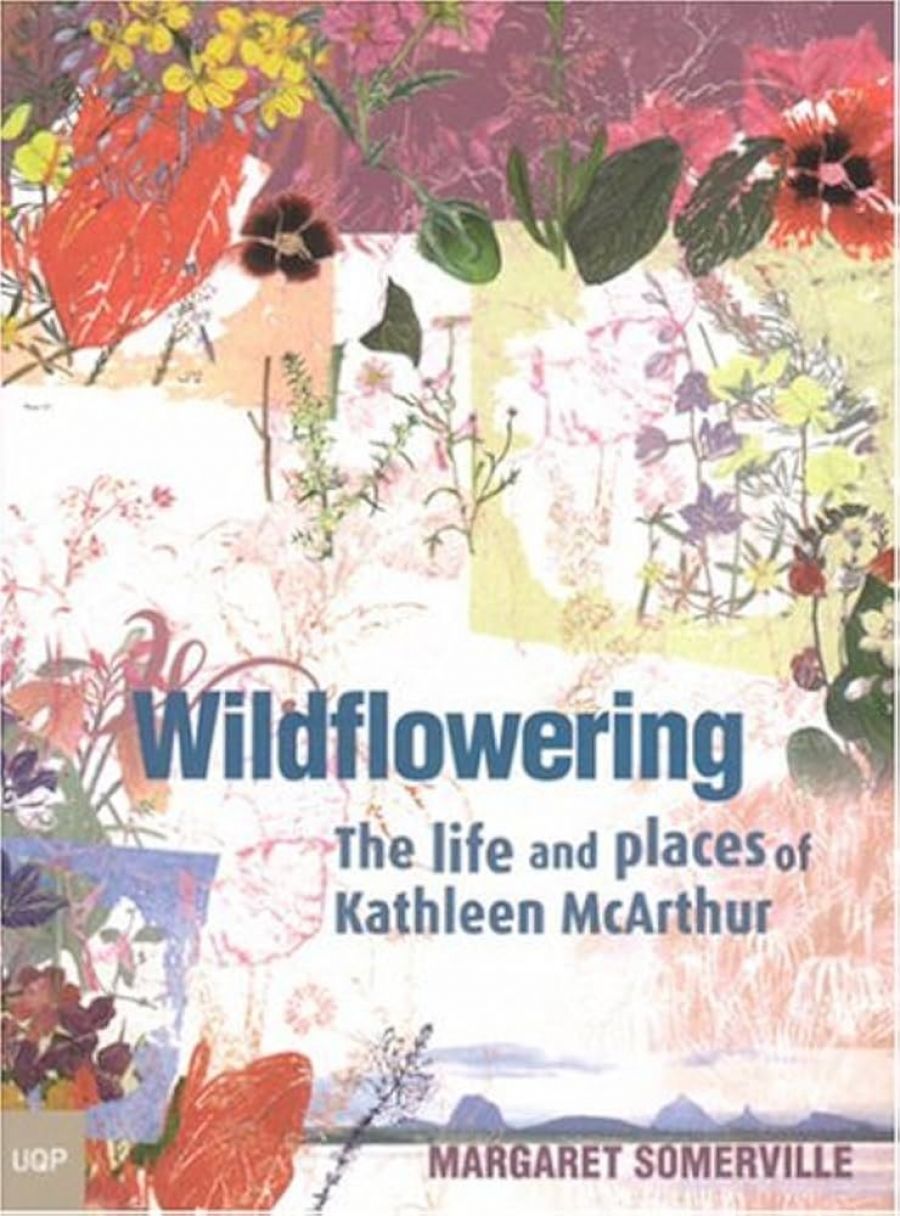

- Book 1 Title: Wildflowering

- Book 1 Subtitle: The life and places of Kathleen McArthur

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, $24.95 pb, 250 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

McArthur’s world, for sixty years, was the ‘wallum country’ (the Kabi word for a hardy species of coastal banksia) around her home at Caloundra, on Queensland’s Sunshine Coast. In the early 1990s Margaret Somerville made several visits to McArthur’s home, Midyim, immersing herself in the atmosphere of the place and performing the rituals of daily life: walking the ‘silver sand track’ of the Currimundi Reserve, swimming mornings and evenings at Kings Beach, and taking part in the cooking and sharing of food. She talked with the artist, read her writings, listened to her stories and pored over her paintings, including the Wildflower Room that McArthur painted in her home in 1957, its walls ‘a riot of massed colour and form’.

The book that resulted from this productive exchange is a deceptively simple but richly layered text, a female poetics of the connectedness of body and place, of body in place. It incorporates the author’s own journey as she starts to ‘think about landscape as a subject, an active being that reaches out to me’. Described as both biography and memoir, Wildflowering breaks new ground in the area of life writing, as far removed as one can imagine from the sterility of an objectively and factually recorded life, written in a prose that is both lyrical and sensual and yet grounded in the practises of everyday living.

Constructed around the places of McArthur’s life, Wildflowering unfolds outward from her home to Midyim’s wild garden, to beach and the concept of the ‘living beach’, to the ‘body of sand’ that is the dune system of Cooloola National Park, and to the ‘body of water’ that is Pumice stone Passage. We gradually understand that McArthur’s engagement with her landscape is a continual learning process of intimate, detailed observation of the rhythms of life: she learns beach ecology by recording tide, wind, and weather cycles, conduct bird surveys of her region, and marks the seasonal cycles of wildtlower bloomings. In her eighties when Somerville visits, McArthur can no longer cross the tidal estuary to enter the wallum, so the author becomes her recorder, in her turn learning the intricacies of this landscape.

When McArthur became what she called ‘a botanical illustrator’ in the 1950s, she wanted to enable Queensland people to see their wildflowers as she saw them. Believing that white people’s consciousness was of British flowers and landscape, she maintained that ‘when the mind opens the flowers bloom’. This extended understanding of place of the comprehension of one’s historical place in the landscape suffuses this text. As Somerville lies in Judith Wright’s old house at Boreen Point, listening to rain pelting on the roof before making what is to be a spiritual journey into the wilderness, she is haunted by lines of Wright’s Cooloola poem: ‘the invader’s feet will tangle / in nets there and his blood be thinned by fears.’ The Aboriginal people of Cooloola, Flinders passing by in 1814, Eliza Fraser the ‘shadows in this landscape’ all form part of ‘a genealogy of the present’.

One feature of McArthur’ s legacy was her environmental action that helped protect wallum country such as Currimundi and Cooloola from erasure. Another part was her understanding of the land, drawn from her own intimate knowledge of it and also from Aboriginal knowledge; how, for instance, wallum country needs regular fire for wildfires to propagate. What we learn from Somerville’s book is that we can all play a role, however small, in preserving the land.

Wildflowering marks a development in Somerville’s own body of writing. Her knowledge of feminist and postcolonial theory underpins this text, but, unlike some of her previous writing, it wears its scholarship lightly, and there is a new richness and beauty of language. Both flashy and transcendent, this writing reflects all the senses as it celebrates the interconnections of body and landscape: ‘Through the movement of my body, buffeted by the lake or quietly gliding around the river’s bends, I would know this river even without sight. To look at the river is to touch its silky surface… through the river I enter Cooloola.’

The book itself is a lovingly created material object. Inside, the rough-edged paper is etched with delicate black-and-white scatterings of McArthur’s wildflower drawings. Each chapter opens with a boxed fragment: a diary entry, a word painting, a statement from an environmental campaign, a letter from Judith to Kathleen. All is contained in a wrap-around cover that glows with wildflowers.

Comments powered by CComment