- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Cultural Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Imagining Australia collects nineteen essays from a 2002 conference on Australian literature and culture at Harvard University. Of course, as the proceedings of a conference, it is on occasion hard work. There is something about conferences – the dedication of their audiences, perhaps, or the vulnerability of their speakers – that encourages a somewhat defensive formality. That said, almost every essay in this collection repays a reader’s investment with interest: in describing the history of Australian literary journals; offering a new direction for Australian pastoral poetry; providing surprising perspectives on popular Australian myths; or looking at how contemporary poets use form.

- Book 1 Title: Imagining Australia

- Book 1 Subtitle: Literature and culture in the new new world

- Book 1 Biblio: Harvard University Press, $59.95 hb, 399 pp

Some essays stand out. Kevin Hart’s account of Judith Wright’s poem ‘The Lost Man’, for instance, serves as an exercise in how to read. ‘The Lost Man’ begins:

To reach the pool you must go through the rain-forest –

through the bewildering midsummer of darkness

lit with ancient fern,

laced with poison and thorn.

You must go by the way he went …

It ends: ‘you must find beneath you / that last and faceless pool, and fall. And falling / find between breath and death / the sun by which you live.’ Hart discovers an additional source for Wright’s poem in Bernard O’Reilly’s once popular but now largely forgotten account of finding three ‘lost men’ who survived the Stinson plane crash in the McPherson Ranges: two who stayed with the plane and lived; one who went in search of help and died. In Green Mountains (1941; reprint 2000), O’Reilly records:

I followed the Englishman’s tracks into difficult and dangerous country … I expected to find him lying on the broken blue rocks at the foot of that drop, but found instead that he had gone on, crawling this time – around four more waterfalls. Around him in the green twilight of the lofty jungle was the unearthly beauty of palm, fern, orchid and vine; beside him tumbled the wild creek and from around a bend the deep musical note of the waterfall dropping into a deep black pool.

Hart’s account of how the poem draws on this source demonstrates how to define a poem’s relationship to its world and maker without losing sight of its distinctive style and effect.

Frank Moorhouse provides a different perspective on the relationship between facts and art when he tells the story of researching his book about the League of Nations, Grand Days (1993); finding, when the book is pretty much written, that there is, after all, a survivor from the complicated, optimistic years he had been reading about in archives. When he meets this survivor, Mary McGeachy, she declares: ‘You must tell me all about myself.’ Later, he meets the daughter of one of her friends at the League who confides, ‘She was my father’s mistress. I believe she had a child by him’ – and so it goes on, this pleasantly gossipy story of coincidences.

Other essays in this collection point to a more vexed relationship between Australia’s history and its stories. In ‘Dead White Male Heroes’, Susan K. Martin suggests that Australians choose victims as their heroes – Ned Kelly, for instance, and Ludwig Leichhardt – to avoid confronting their role as perpetrators of harm. Tony Birch argues that some contemporary Australians identify, falsely, with Indigenous victims to appease their conscience, representing Paul Keating’s celebrated Redfern speech as ‘facilitating a mythology whereby those who have done little of substance to shift the racial status quo in Australia point to it to legitimate their humanitarian credentials’. Birch is highlighting the fact that the Sorry March in May 2000 led to no legal or constitutional change: ‘how do we explain the gulf between an expression of grief and public support for Indigenous people during an energised socio-political event but witness an absence of political will when it matters most?’

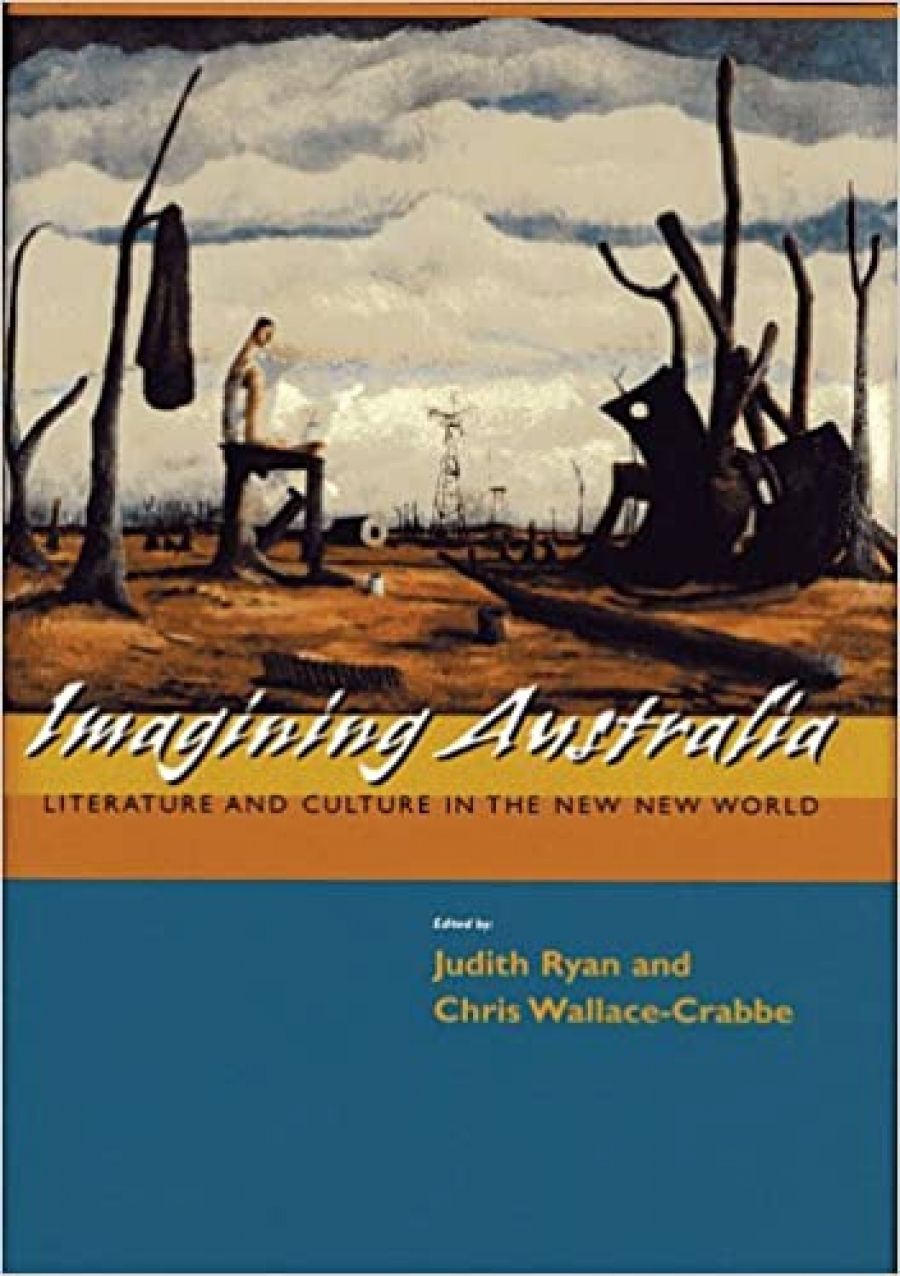

A number of essays in this collection look at how Australians imagine the bush: as a rallying point for national identity; and as the focus of concern about Australia’s history of violence and its representation in art, as well as law, as terra nullius. To that end, Imagining Australia takes as its cover Russell Drysdale’s 1941 painting, Man reading a newspaper. Chris Wallace-Crabbe explains in his introduction that in choosing this painting the conference organisers intend to challenge whether, and how, and why, the image of a white man in a desert is, in Lucy Frost’s words, ‘the “brand” we use to imagine ourselves’.

In one of the most wide-ranging and thought-provoking essays in this collection, Frost argues that Drysdale’s painting belongs to the ‘narrative paradigm’ that Henry Lawson established in the 1890s as part of a nationalist movement to achieve Federation. Certainly, Drysdale’s image has a monumental quality that seems to take it out of time (though the man is reading a newspaper). All the same, Frost’s comparison raises questions about whether Lawson and Drysdale do in fact imagine the same kind of landscape: ‘bush all round’, writes Lawson in The Drover’s Wife: ‘The bush consists of stunted native apple trees.’ It also raises questions about whether they use landscape to the same purpose; or whether, in Drysdale’s time, writers and artists (such as Patrick White in Voss or Sidney Nolan in the Ned Kelly series) use landscape not to imagine and romanticise the settler’s struggle with nature but to imagine the settler’s inner desert spaces – claiming the country in a notably different way.

Frost’s essay, like Ryan and Wallace-Crabbe’s introduction, and Robert Dixon’s account of William Robinson, is intriguing enough to make a reader want further assessments of Australian art in this collection. Frost’s essay finishes with a glimpse of women’s lives, which it would have been pleasing to see in more detail: ‘the cases of the 25,000 women transported to New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land between 1788 and 1852.’ Frost shares the identification document a convict clerk composed about ‘Maria (a slave)’ from Honduras:

Number: 81

Trade: Servant of all work

Height without shoes: 4’11”

Age: 18

Complexion: Black (a woman of color)

Head: Large

Visage: Broad oval

Forehead: Small, round

Eyebrows: Small arched …

Frost also includes Maria’s own account of why, aged fifteen, she killed ‘Wm Mair a Builder’: ‘I was beat by him & he got a knife we scuffled together & in the scuffle the knife entered his body and killed him.’

Comments powered by CComment