- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Bridget Jones stripped bare

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

First, the good news or the bad news about this novel? Perhaps the bad. Presenting the worst face of a character to the world is not in itself fresh or especially amusing any more. We are overrun with sitcoms reflecting us, warts and all. Bridget Jones was among the first of these types of characters in popular fiction, and I was variously amused and pained by her hapless and heart-warming antics. More recently, the anonymous Bride Stripped Bare startled me for the statutory fifteen minutes, and left me wondering where all the attractive taxi drivers were hiding. In Alison Says, a conflation of the above, I found the central character, Maggs, to be a bit tiresome – and tired. Maggs is a 24-year-old drama teacher who has recently been dumped. Two months later, Jamie, the ex-inamorato, becomes engaged to Lorelei, aka ‘the Rhine slut’. In the wake of these events, Maggs is emotionally vulnerable, but it’s all rather in the manner of someone in an arrested state of adolescence. Suzanne Hawley’s Maggs is a stock characterisation based on the humour of self-absorption and victimhood, narcissism and obsession. Hawley’s novel does not fully realise the key ingredient of chick lit: a central character that the reader either loves or loves to hate.

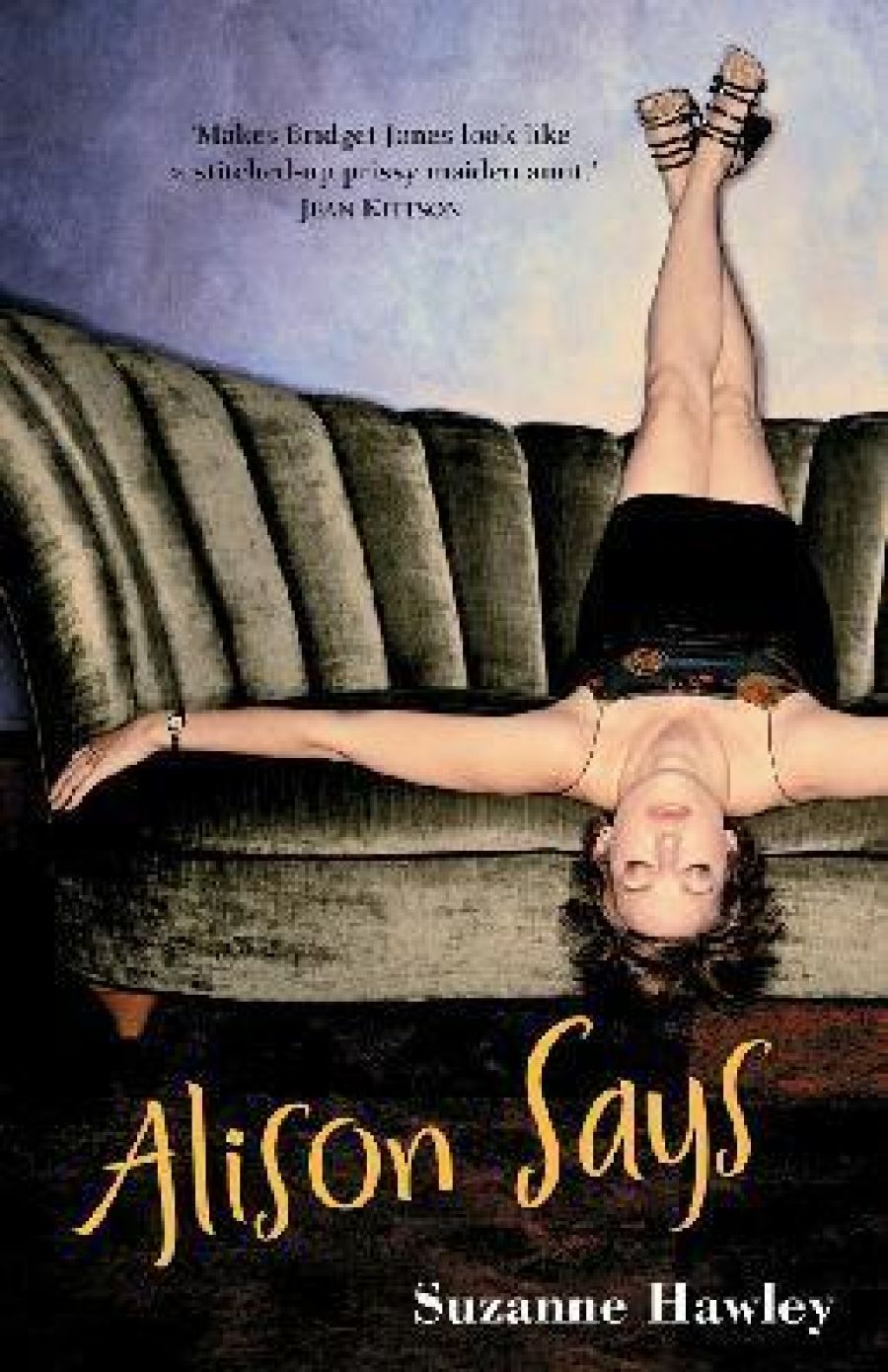

- Book 1 Title: Alison Says

- Book 1 Biblio: Random House, $22.95 pb, 220 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

That’s not to say that this novel is without entertaining moments, or moments of uncomfortable self-recognition. It’s funny and farcical at times, but in the end it’s too predictable. A type of delicious cringe humour is, I think, Hawley’s intention: those moments when, squirming, we cry out, ‘Nooooo, don’t do it!’ Sometimes she achieves this, but too often in Alison Says we instead find ourselves thinking, ‘Here she goes … again’. Hawley does not provide enough moments of real uncertainty to hold us in thrall.

Hawley also relies too heavily on other conventional elements to enliven the novel: a family that lacks good taste in all things; a stray cat in need of a home; a revenge plot you can see coming a mile off; and frequent name-calling. These make for predictability and banal humour. The reliance on stock elements results in a narrative that is not always inventive enough to engage us.

The good news: Hawley does have a genuine comic eye; there are laugh-out-loud moments in this novel as Maggs’s best-laid plans go astray. Farce is central to these moments. Hawley has written mostly for television; one can imagine that the novel translated for the screen, and enhanced by its visual dimension, could be successful. Indeed, Alison Says reads much like one of those novels pumped out in the wake of popular films, the result usually being a ‘poor prose cousin’ of the original.

Hawley’s theme of obsessive romantic jealousy is one that always has currency. Maggs’s efforts to inflict pain and chaos on her successor and her attempts to win back Jamie are sometimes very funny, especially when Maggs is the one who is undone. Her star turn as Debbie Reynolds bursting forth from an oversized cake at a buck’s night party to perform ‘Singin’ in the Rain’ is memorable.

In matters sexual, Maggs has no inhibitions. Descriptions of the ‘odd job man’ as sex object, his ‘gigantor awakening’, and of Maggs’s own desires, ‘I was hoping for … his raging beast to push into my buttocks, at which point he’d bend me over the kitchen sink and fuck me stupid’ are for those who prefer titillation via the language and imagery of rough-trade sex. Maggs informs the reader at one point that her snatch is ‘throbbing endlessly’ and is at the mercy of a – wait for it – ‘giant member’. Surprise, surprise. Maggs’s definition of good sex is hard, fast and at hand. If that’s how you like it, or even if you don’t, you might enjoy some of the encounters in Hawley’s novel. There’s a school boiler room scene or two that are deftly managed to achieve climactic levels of sexual farce.

Behind the scenes of Maggs’s chaotic life lurks the Alison of the title, her ‘shrink’. Hawley makes good use of the humorous opportunities in their therapeutic encounters. Alison’s grappling with Maggs’s implacable self-absorption proves to be the ‘shrink’s’ undoing and results in one of the funniest scenes in the novel.

When Hawley eventually brings Maggs to a reflective halt, it’s a relief. Hawley also hints at what the reader already knows – Maggs is not necessarily poised for ready redemption. Ugh …

Comments powered by CComment