- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

If you are regretting the passage of another summer and feeling nostalgic about the lost freedoms of youth, Sonya Hartnett’s latest novel, Surrender, may serve as a useful tonic. In Hartnett’s world, children possess little and control less, dependent as they are on adults and on their own capacity to manipulate, or charm ...

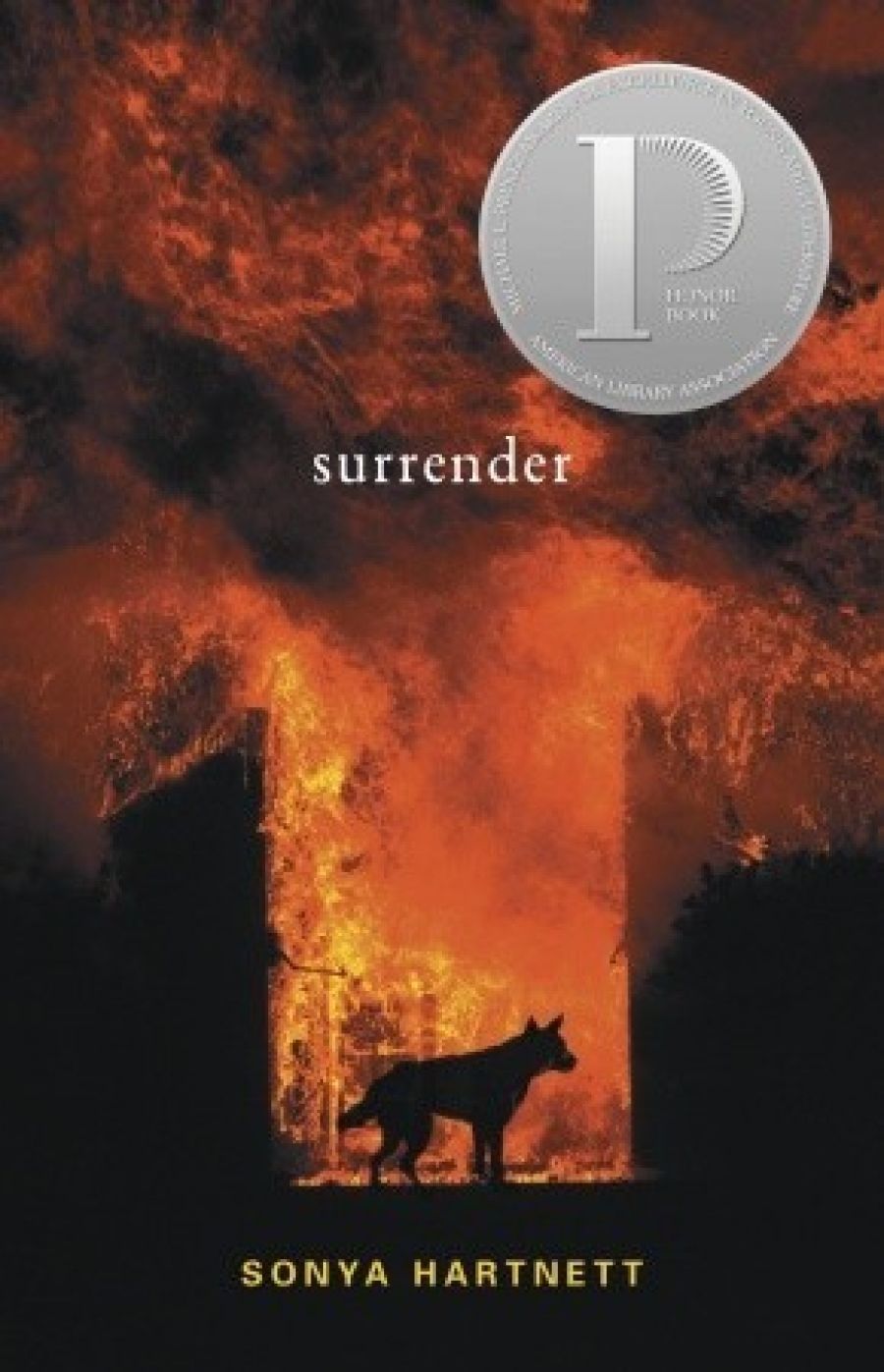

- Book 1 Title: Surrender

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $29.95 hb, 245 pp, 0 670 02871 1

Chapter by chapter, Gabriel and Finnigan take turns to tell the story. Finnigan is Gabriel’s secret confederate and wild counterpart: ‘We were the same height and same age and built along similar leggy lines, but he was a hyena while I was a small, ashy, alpine moth.’ If Gabriel is the angel, then Finnigan is the ‘midnight raider of kitchens, the sleeper-in-woolsheds, the bareback horse-rider, the bather in rushing streams. He is dirt under fingernails …’ (If you’ve read Thursday’s Child, Finnigan will make you think of Tin, the tunnelling boy, the uncontrollable creature of earth.)

Early on, we learn that Gabriel and Finnigan have made a pact: ‘I’ll do the bad things for you,’ says Finnigan. ‘Then you won’t have to. You can just do good things.’ This is a pact that enables Gabriel to survive his repressive parents: his vigilant, reclusive, religious mother and his father, ‘simply a frightening man’. It helps Gabriel to endure his loneliness at school, and his guilt about the death of his younger brother. Thus he retains his sense of innocence and still gets what he wants, at least for a time.

Gabriel and Finnigan’s pact also allows Hartnett to enact that enduring theme in Gothic literature: the desperate closeness, the fascinated interdependence, of what you might call good and evil. Surrender is a novel where the characters also work as symbols – even the dog that Gabriel shares with Finnigan is called Surrender – and the plot is about as close to allegory as a murder mystery can be.

Hartnett specialises in isolated characters and places, but Surrender seems more intensely claustrophobic than her other novels. With Gabriel and Finnigan telling the story, it becomes difficult to work out how much of what they say is an elaboration of madness or deceit. As Gabriel warns, ‘I am Gabriel, the messenger, the teller of astonishing truths. Now I am dying, my temperature soaring, my hands and memory tremoring: perhaps I should not be held accountable for everything I say.’

In this way, Surrender resembles Robert Cormier’s astounding 1981 novel, I Am the Cheese – not surprisingly, perhaps, for Hartnett and Cormier corresponded for some years before he died. In I Am the Cheese, as in Surrender, the force moving the story forward is the narrator’s memory taking us back; and, possibly, taking us in. The narrator plays this cat-and-mouse game with the reader, and the less certain we are of him, the more closely we identify with his uncertainty about what he can believe and trust. Both novels draw the reader into a disturbed and heightened imaginative world: what they lose of reality they make up in intensity.

With all the secrets and uncertainty in Surrender, Hartnett has found a situation that suits her style. Above all, she is good at creating an atmosphere; so, though many terrifying things happen in Surrender, the atmosphere remains much stronger than the plot. Of course, this is one effect of creating protagonists who are, or feel, powerless; who do not so much take the story forward as watch the world close in. But it is also an effect of Hartnett’s writing style.

She has mastered the short, intense sentence, so her novels are evocative and also fast-moving. In Surrender, for instance, she uses disturbing metaphors and analogies – ‘The digging tools they’re using are silver as werewolf bullets. The colours scream so loud at me that I clap my hands to my ears’ – until the entire world of the novel seems precarious and sinister. As Hartnett once remarked, ‘I’m not so much a storyteller as … a troublemaker’. And Surrender is trouble: weird, darkly compelling – and finally discomfiting, as it intends to be.

Comments powered by CComment