- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Mr McInstoush

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

No Australian native son blazed brighter than Hugh D. McIntosh (1876–1942). Here is a lively biography of a Sydney boy who left school aged seven and rose to be the Squire of Broome Park in Kent, the stately seat of Lord Kitchener. McIntosh – contender though he became for a seat in the House of Commons – remained always an Australian. At Broome Park, a cricket pitch was laid down with ten tons of Australian earth, imported so that the visiting Australian Test team might practice on their native soil. The McIntosh ‘coat of arms’ came not from the College of Heralds but from the studio of his old mate Norman Lindsay. The very doctor who delivered him at birth was Charles Mackellar, father of that Dorothea who celebrated our ‘sunburnt country’.

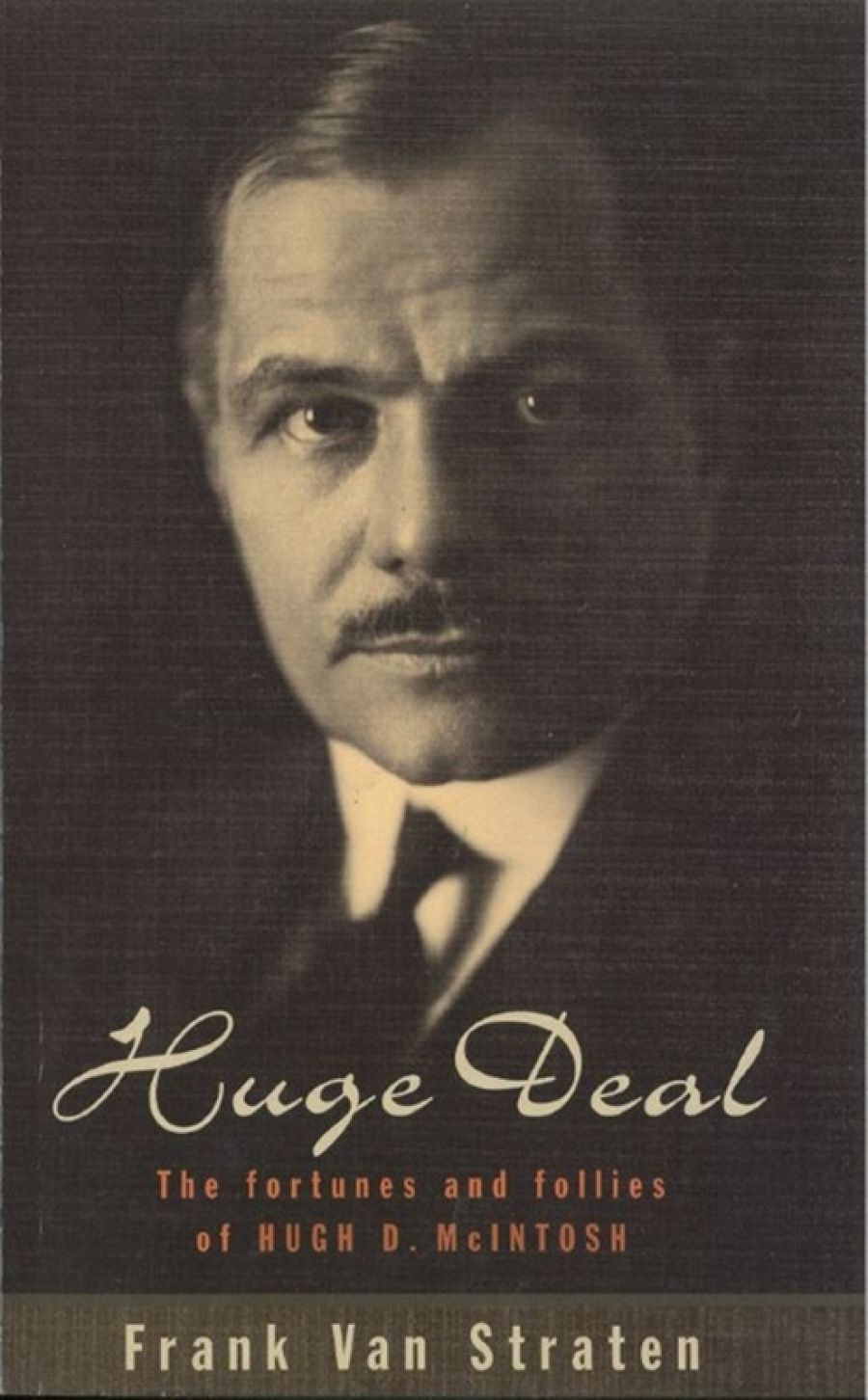

- Book 1 Title: Huge Deal

- Book 1 Subtitle: the fortunes and follies of Hugh D. McIntosh

- Book 1 Biblio: Lothian, $34.95pb, 320pp, 0 7344 0680 0

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

In his teens, Hugh did all manner of knockabout work: ‘ore-picking’ in Broken Hill, farm labouring, surgeon’s assistant. And he squeezed in a little night schooling. Then into cycle-racing, as tough and crooked a sport as you would find. Then boxing, when bare-knuckled bouts were just going out of fashion. Well below medium-height, Hugh was nevertheless broad, strong, and fearless. Real fisticuffs in the ring helped build a solid foundation for his fame, and for his several fortunes as a promoter. In 1895, employed as a barman, McIntosh married a pretty teacher of painting, May Backhouse. They were both about twenty-one. May was a strong-minded woman with interests of her own. When Hugh took over the Tivoli Theatres, she became costume designer. Unperturbed by his many dalliances, she was his close partner to the end. The Sydney dwellings of the McIntoshes were mansions of ever-increasing size and extravagance. But when Fortune frowned, they took a humble house near Centennial Park, and May pawned her furs and jewels.

In a fight-promoter’s coup of 1908 (which must have startled Melbourne rival John Wren), McIntosh matched Tommy Burns, the reigning world heavyweight champion, against Jack Johnson, a black man from Galveston, US. It caused a worldwide sensation, Jack London and H.L. Mencken being but two of the greats who voyaged to Australia specially to see the fight at McIntosh’s newly built enormous stadium at Rushcutters Bay. (‘Texas with a tin roof’, Bob Hope called it, many years later.) A sell-out crowd watched Johnson shatter Burns, but it was an unpopular verdict: no ‘nigger’ should triumph this way over a white man. McIntosh creamed the ‘spin-offs’ in a way that might have shown points to today’s marketers of Harry Potter. A film of the fight was showing three days later in the cinemas – largely Hugh’s cinemas; the contestants made well-remunerated personal stage appearances – in Hugh’s Tivoli Theatres. Johnson’s shining black muscles, we are told, were appreciated especially by ‘the fair sex’, now forgetful of his racial unacceptability. The ‘tight fit’ of his pants in profile view was much remarked. His ‘endowment’, impressive in any case, had for the occasion been enhanced by liberal swathing in gauze bandages.

McIntosh was made, but the racism of his promotion today seems startling and repugnant. The fight was frankly billed as a trial of racial supremacy – white race against black. Johnson was frequently insulted; even his sponsor called him a ‘black swine’ and threatened to blow his ‘dirty black head off’ with a revolver. Yet on an earlier visit, Johnson had enjoyed an unconcealed affair with Sydney society girl Lola Toy. Frank Van Straten wisely sees that all this was in the past and spares us retrospective moral clucking.

Then it was into newspapers, with the purchase of a controlling interest in the Sunday Times Newspaper Company Limited and its stable of rags. There was little immortal journalism, but the pace was lively. A rival proprietor, in print, referred to the newcomer as ‘Mr McInstoush’. Hugh revelled in the Sunday Times boardroom, where lunches of boundless extravagance and endless duration became the order of the day. ‘McInstoush’ travelled the world in high luxury, meeting Nellie Melba, H.G. Wells, Winston Churchill and almost anyone he fancied. Assiduous cultivation of the Labor Party earned him membership of the NSW Legislative Council to which he clung for years (together with its free travel pass), though his attendance and speeches were rarities.

Buccaneer, tricky, tough but rarely mean or hateful, handsomely generous to those who had served him or who were down on their luck, there have been many far less attractive Australians than ‘Huge Deal’. His memorial may be seen today in Martin Place, but it does not carry his name: it is the Cenotaph, which McIntosh persuaded Premier J.T. Lang to build.

Our thanks to Frank Van Straten for such an amiable, clear and copiously sourced story; also to his publishers, who have produced, in Australia, such an attractive book without, I believe, a single typo.

Comments powered by CComment