- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Half-breeds and go-betweens

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Juan Davila is a major figure in contemporary Australian art. His fluent appropriations of other artists’ styles and motifs (all neatly numbered and labelled), combined with an assertive iconography of sexual desire and transgression (all bare thighs and thrusting tongues and mutant genitalia), made him one of the most interesting painters of his generation – the postmodern, theoretical, Art and Text push of the 1980s. He has represented his country in northern hemisphere exhibitions from Paris to Banff, and has maintained strong connections across his native Latin America. The New South Wales Vice Squad’s infamous impounding of Stupid as a painter in 1982 cemented the artist’s ‘bad boy’ reputation with the general public, as well as within the art industry, while his painting of a semi-nude, hermaphrodite Simón Bolivar giving the finger actually created a full-scale diplomatic incident involving Chile, Venezuela, Colombia and Ecuador. Davila’s regular output of polemical essays, his gloriously rude lampoons of political leaders and his more recent, sober protests against refugee detention have ensured his work has a place in public discourse. A comprehensive survey is long overdue.

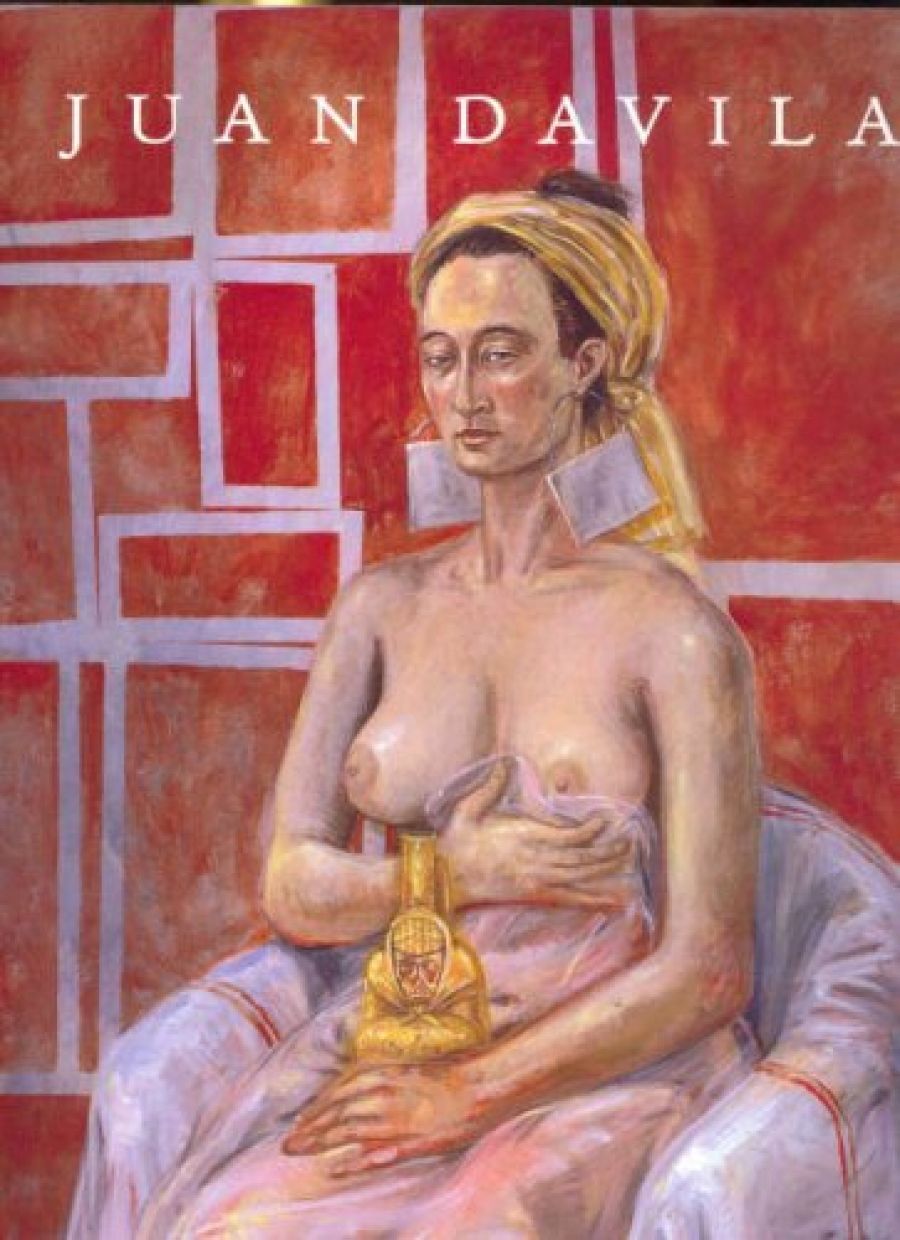

- Book 1 Title: Juan Davila with Guy Brett and Roger Benjamin

- Book 1 Biblio: Miegunyah Press/Museum of Contemporary Art $59.95 hb, 254 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

This book starts with an essay by Guy Brett, an extended meditation on the artist’s work as it pertains to relations between indigenous Indian and Spanish conquistadors and to associated notions of sexuality, miscegenation and identity – in short, to the world of the mestizaje: half-breeds, mimics, go-betweens. It is an entirely appropriate beginning, not only because of Davila’s long-standing engagement with the theme but because the volume itself is just such a hybrid: the authorless, bastard offspring of an art museum exhibition and the glamour imprint of a university publisher.

The essay is also appropriate in the richness of its underlying irony. Guy Brett is an Englishman, from the nation of the original über-imperialists of the modern age, the colonial masters of nineteenth-century Australia, whose queen is still our head of state. (One of my personal favourite Davilas is The Australian Republic [2000], an only partly finished painted empty picture frame.) Moreover, as an anglophone, Brett speaks and writes the language of Britain’s American successors, the language of the museum/market artistic hegemony which has long been one of Davila’s chief targets. That Brett should be writing of Latino resistance and liberation from an historico-linguistic location (if not a personal position) of Anglo privilege and power is as topsy-turvy and carnivalesque as that Davila the Santiago patrician should be painting that same Latino resistance, or that Davila ‘the wog’ should be painting Anglo mythologies.

Brett’s essay is in fact enormously helpful in explaining particular Latino references in the artist’s iconography, from the armed devils and angels of Indian-Catholic syncretism to the popular-comic figure of Verdejo, the uncouth roto or bumpkin. Roger Benjamin’s more extended dissertation is an engaged and engaging look at four particular aspects of the artist’s work. He explores the strategies of montage or ‘citationalism’, the aggressive picturing of sexuality, the slighting or scathing references to Australian art history and politics, and the significance of variant modes of presentation (from muralismo Mexicano, to interior décor collaborations with Howard Arkley, to street market-style floor layouts, to the most recent, gilt-edge academicism).

Beyond these two key essays, the textual content of the book is, however, a bit thin. There is a handful of reprinted articles by Davila himself, postmodern polemics really, ex cathedra assertions, rather than analysis or argument. There are half a dozen extended captions to individual pictures, a list of all the works reproduced in the book, and a comprehensive but rather bald curriculum vitae. A chronological biography, and further contextualising and interpretative writing, would have been welcome. Make no mistake, Davila is difficult. Any attempt at an item-by-item, blow-by-blow deconstruction of a given work is always frustrated by the chaotic plenitude of Davilan visuality: the happy mixture of signs and signifiers, the flows and stoppages of meaning across cultures and nations, the pictorial and political non sequiturs, the polymorphous-perverse sexuality. As Brett puts it, ‘his painting is rude, libidinal, uncomfortable, complex, uncontained, fastidious, unschooled, highly schooled, erudite, argumentative. He switches between refinement and tackiness, mimicry and invention, disgust and celebration, scorn and affection.’ His sources are so various, his live models so anonymous, his wit so deadpan, his obscenity so extreme, his learning so profound, his disdain so broad as to render his work quite incomprehensible to the outsiders which we all are.

Even now that he has abandoned modernist fragmentation (because ‘neo-capitalist’) and returned to a form of social naturalism – of Courbet-style ‘real allegories’, of Manet-style ‘paintings of modern life’ – Davila continues to confuse. The pigment may be thinner, looser, more translucent than previously, but the meanings are still opaque. In the end, the easiest thing is probably just to allow yourself to be seduced by the sheer painterly bravado. There are more than two hundred reproductions in Juan Davila. Bugger the confusion.

Comments powered by CComment