- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

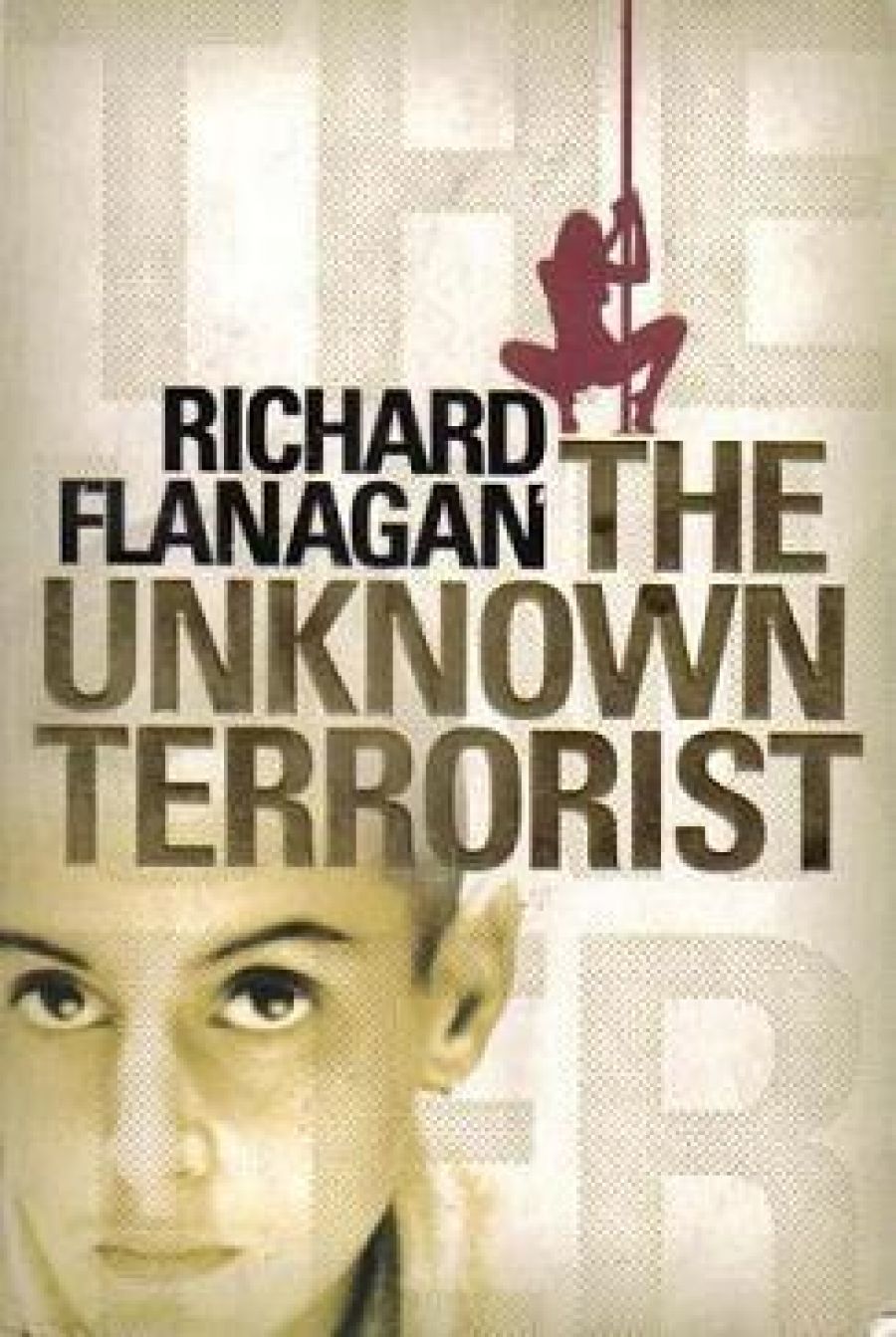

- Article Title: Pole-dancing

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Richard Flanagan came to prominence some years ago like a collective delusion. Death of a River Guide (1994) sent a thrill through the literary community because of the raciness of its never-ending stories and in 1995, the baleful Year of Demidenko, we found ourselves giving the last of the Victorian Premier’s Prizes for new fiction to the Tasmanian arriviste who wrote fabulism like a Douanier Rousseau among the thylacines. Not long afterwards, Flanagan persuaded the producers to allow him to direct the film of his second novel, The Sound of One Hand Clapping (1997) with nothing but a few supervisory tips from Rolf de Heer by way of experienced guidance, a feat of Cocteau-like virtuosity or snake-oil powers of persuasion all but unprecedented in national (let alone Tasmanian) history.

- Book 1 Title: The Unknown Terrorist

- Book 1 Biblio: Picador, $32.95 pb, 325 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Then Gould’s Book of Fish (2001) came among us like a classic or a revelation. This was the big haul: a powerfully imagined magical-realist novel, intimating an alternate history and a world of convict and contrapuntal stories, hooped together in a makeshift style, gliding from purple to parody to verminous vernacular like some miracle of oracular ocker-dom.

Here at last, everyone thought, was the Ancient Mariner of Australian fiction, a mesmeriser in the high modern and postmodern manner. A writer thicker in texture than Carey but more local in inspiration and more mythical (always a good combination) and with a sheer power of inventiveness that recalled the tutelary gods – the Marquezes and Rushdies – who had shown how a bright and blood-bedabbed stream of fable, issuing in the first instance out of Borges, could translate into a vision that disrupted realism in the direction of narratological enchantment but contained, for all that, an implicit politics.

So much for the all-too-printable legend. Gould’s Book of Fish is a great work of magical realism the way Paul Keating’s republic is a great political achievement. It incorporates a great idea for a novel – one that ravished me, it has to be admitted, when I read the rough draft of the first chapter and subsequently published an edited version of it in The Best Australian Stories 2000. It captured the nation’s imagination, notwithstanding this, with able judges such as Brian Matthews thinking that, for all Flanagan’s roughness, the river guide had won through. The reputation of Gould’s Book of Fish set its girdle round the earth, with lavish praise from Michiko Kakatani in The New York Times, and from the Irish novelist John Banville, who, you would think, could pick a bogus novel at fifty paces. It could even be glimpsed on Big Brother in the hands of Saxon, the blonde surfie boy.

It is too simple (it has to be) to say that Gould’s Book of Fish was the great parochial monster novel we had to have and that it represented a kind of bizarre coupling of naïve skills and great ambitions under the spotlight of a world that could make out a kind of book but not a quality of achievement. The difficulty with Gould’s Book of Fish is that it constantly slips into bathos and self-parody, not by a principle of design but by a logic of inadvertence. It’s not that the author deliberately writes badly in order to indicate the limitations of language, as Joyce abidingly allowed himself to do in Ulysses and elsewhere. Nor is it that he marshals his awkwardnesses to sculptural effect, as Murray Bail does with great artistry. No, he embraces bathos like a belly flop, he constantly skids into infelicity after infelicity, singing no tune, telling no tale, forever alluding to the book he’s writing rather than writing it.

The give-away is that he can’t achieve precisely the sorts of parodistic effects that you can see the language striving for (i.e. this bit of rhetoric, that echoic effect) so that the upshot is a hoax-like work in the manner of ‘Ern Malley’ in everything other than the sincerity of its author’s pretensions, except that it is apparent that, in this case, it’s not just the emotions who are not skilled workers.

It is a dissenting judgement to say so, but there is an aspect to the clamorous talent of Richard Flanagan that is enough to make one think (pace Cocteau and polymath ambitions) that what he needs is the kind of thing that most of the great postwar film directors apart from Bergman and Pasolini knew they needed, even though they were auteurs: the talents of collaborative scriptwriters.

Richard Flanagan’s new novel, The Unknown Terrorist, is as different from Gould’s Book of Fish as it is possible for a book to be. It is like passing from Zabriskie Point to an unusually dark episode of Blue Heelers, or to some new chapter of hitherto repressed pessimism in the fiction of Matthew Reilly. The new book is within cooee of being written in the style of airport fiction, if that were not too loose a category to allow for stylistic distinctiveness or the kind of concentrated seriousness that is part of the package here.

It is roughly written, as Flanagan’s work always is, with passages of what looks like journalese blending into a slightly overworked and bombastic literariness, though the overall effect is fluent, rapid and conducive, with the odd smudge here or there, to a kind of window-pane effect which, although being a long way from Carveresque clarity, represents a relaxed and flexible style in which to spin a yarn.

The complication with The Unknown Terrorist is that a yarn of the mind-soothing escapist kind is the last thing that is envisaged here. This is Flanagan’s novel about the ‘war on terror’ and the way it turns the citizenry, especially the marginal citizenry, of the modern state (Australia in this instance) into so much fodder for body bags, as a fascistic logic feeds the monster of propaganda cynically maintained by the lackeys of the manipulators of power.There is no denying that this is one of the Big Themes of contemporary fiction and has been for a good deal longer than our post-9/11 dispensation allows us to remember (not least because, among the American masters, Don De Lillo, in novels such as Mao II [1991], has consistently been preoccupied with the interface between terrorism and paranoia). In any case, the subject is like a poison or a drug in the water supply of contemporary creative endeavour. As I write, the Melbourne Festival is about to host Tim Robbins’s restatement of Orwell’s 1984 for the age of the war on terror; and one of the most notable Australian plays to appear in recent years is Steve Sewell’s Myth, Propaganda and Disaster in Nazi Germany and Contemporary America, which traces the entropic logic of Götterdämmerung in societies committed to extremity and to the suppression of those it decides, by ideological fiat and gradualist logic, to see as other and to cast out as strangers.

It is an extreme dramatic logic that Sewell embraces, of considerable political depth, and with an excruciated but logical progression. Flanagan has a much simpler story (which is also simpler in its representation), though it is, by the same token, a disquieting fable for our interesting times.

The Unknown Terrorist is his story of the pole-dancer and the terrorist. The Doll, as she is known, is a young woman who was subjected to the roving hands of an awful father and whose mother is dead. She takes up pole-dancing as a consequence of griefs which are not at first revealed to the reader, but which leave her bereft of any ambition other than to cover herself in money (literally and symbolically) as well as to adorn herself in Prada and to wield that Louis Vuitton bag. She lures men like flies and rends them like lace. She does her famed Black Widow routine and they stain their pants. She is a halfway decent damaged woman. There is a moment when she flinches at the possibility, then the aftermath, of what is done by brute force to an Asian comrade-in-arms, but she does not prevent it. She can flicker into sympathy for a beggar, she can flicker out.

The Doll’s only friend is the mother of a young boy. One day she’s at the beach with the two of them when the boy is pulled out to sea, only to be rescued by a young Middle Eastern man with the looks of a Greek god. The Doll goes to bed with him. He is gentle, sensitive, a far cry (because he’s human and supple) from the stereotypes she deals with – the crippled rich men, the creepy television reporters, so much dreck, so much exploitation, despite which she maintains her lofty invincibility, thinking only of the property she will buy with the money she amasses from the masturbating horde.

Then, like the nemesis we await, it all falls apart. The media brandish her lover’s face as that of everyone’s Worst Fears, and the Doll is branded as the terrorist’s collaborator. The latter part of The Unknown Terrorist shows the heroine on the run from a world that is part mad, part hardened to any thought of truth. One or two semi-decent policemen stumble and strive to make sense of reality, to pierce through to the truth in a world that wants the lie as a frightening legend to live by.

Two-thirds of the way through the book, we learn, belatedly, what it is that makes the Doll tick, what very human and pulsating desolation has turned her into the partial freak that she is. It forms a strange, forlorn kind of pietà at the heart of this odd but compelling book with tragedy at its heart. The last movement of The Unknown Terrorist is grim, urgent and powerfully dramatised. There is an exhilarating scene where the Doll, gun in hand, meets the man who has turned her into a dead woman walking. It is these latter pages which have a kind of power and an undoubted poignancy that in some ways belies what is manifestly modest and threadbare about a fair bit of the novel.

It makes Flanagan’s new book a challenge to our literary and aesthetic categories, even as it, in a more obvious and clean-cut way, represents a challenge to the dominant political consensus, from both sides of Australian politics, about what terrorism and wars on it might represent (though not perhaps to the dominant view of them among the liberal intelligentsia).

Flanagan is such an odd writer because much of the circumambient scene-making in The Unknown Terrorist is bad in ways that it’s hard for the mind to fathom. The television personality who sets the dogs of suppression onto the Doll is a very slimy customer indeed, but even he is excelled by her patron, the chap she does extra services for, who collects mementoes of international atrocities and other emblems of sadism, of which images of French collaborator girls with shaved heads are the mildest examples. He, by the way, is in a fact a new rich ‘westie’ who has adapted an Italian name for not quite explicable reasons. (Then again, there is a moment of empathy, near his sticky end, with the Doll, and there is also their shared love of Chopin, which is a nice touch.)

But there is a whole aspect of The Unknown Terrorist that seems to exist in a universe of uncomprehended expressionism, the foreshortening and grotesquerie all the more over the top for the lack of comprehension about the adopted method.

People with money are presented as vacuous swine or worse. People in power tend to have a motivated malignity that knows no ambiguity, and the odd officer of the law, high or low, is impotent or hapless in the face of the grinding killer bastards.

Add to this the fact that Flanagan seems to have no understanding of a consumerist world (he doesn’t have to like it, but if he wants to write about it he should understand it), nor anything much in the way of greys shading into blackness in terms of visions of evil. Simply at the level of schematisation and the deployment of necessary skills – appropriate to what is, to a fair degree, a plot-driven book – the good and the bad minor characters should have been introduced earlier and more neutrally.

They should also, if the thriller is the form being tinkered with, be shown as working on more complex endeavours that might intrigue the reader, while the central plot concerning the Doll’s torment can be given an appropriate shrouding and circumstantial credibility. Flanagan shows no sign of having learned from writers as different as Graham Greene or Fyodor Dostoevsky in the ways of using a thriller structure to command the attention and to give dynamic form to a serious novel with a moral dimension.

The Unknown Terrorist both is and isn’t such a novel. It is nearly clueless in its miming of the conventions of the popular novel of suspense, catching a fair semblance of the vacuities of much contemporary narrative style, but not the intricacy of the plotting or the necessary soap-like blather of dialogue that establishes the ‘character’ as conventionally ‘real’, according to accepted, if lower-level, conventions. On the other hand, there is a real poignancy that runs through this anthem to a doomed girl. And the Doll herself does have her own fierce reality, despite the hoops the novelist puts her through in this dystopian circus of dirt and sleaze and dastardliness that makes Sydney into the Big Smoke that chokes the soul.

There is, by the way, a whole mad scatology-as-archaeology aspect to this book, as Flanagan noses his way through an urban landscape the smell of which makes him puke. It is as if the horror and inanity of the war on terror has led him to contemplate the nadir of all political iniquity, and what he’s left with as its human symbol is a kind of King’s Cross of the human soul, which proceeds to appal him beyond all understanding.

And yet, The Unknown Terrorist packs a punch. Why, oh why, given what’s wrong with it? It is partly that this image of a young woman forced to cavort for depraved worldlings and then hunted to the point of destruction has gripped Flanagan’s soul to such an extent that he cannot fail to communicate it. It does have a remarkable viability as the objective correlative of the particular kind of melodrama which Flanagan is making central to his political purpose.

The Unknown Terrorist is, in part, a propagandistic novel in a cause it is difficult not to have sympathy for. If it fails to convince as a credible image of the world (and hence as a viable political critique of its workings), it does nonetheless have the power that comes from the toughness and poignancy of its central figure.

Is it that Richard Flanagan, the putative major novelist, is a bit like the pole-dancer meeting a concocted and hideous destiny in her designer clothes? Perhaps it is, but The Unknown Terrorist is, I think, a better book than Gould’s Book of Fish for all its populist imperatives and its headlong rush to judgment, precisely because the Doll is both herself and the emblem of something.

In characteristic fashion, the book begins with a homespun, somewhat pretentious meditation on Nietzsche and Jesus, which will convince no students of scripture or hermeneutics or philosophy, let alone the reader. There is a writer’s note in which the author acknowledges his adaptation of Heinrich Böll’s plot (in The Lost Honour of Katharina Blum [1974], which Schlöndorff and von Trotta filmed); and there is a pompous note talking about Shakespeare ‘who rarely invented his plots and so well-quarried such sources as Raphael Holinshed’. ‘Well-quarried’, forsooth! ‘Raphael Holinshed’ belongs in the sub-editor’s world of Thomas Stearns Eliot. Flanagan goes on to ascribe Falstaff’s ‘Wisdom cries out in the street yet no man regards it’ to Henry V – never mind that it is said by Shakespeare’s greatest comic character in Henry IV, Pt 1. Flanagan declares that it is ‘a most beautiful line lifted from Proverbs’, as if his own liftings therefore had bardic justification. It is silly because they don’t need any, but in this instance Falstaff is aware of the echo and there is no ‘lifting’ involved: there was a time when people used to quote the Bible.

Not that writers’ notes matter much, but the yokelishness of this is in its way symptomatic. The Unknown Terrorist is a novel, full of driving moral seriousness, written in a debased idiom by a man of some vision, and in the midst of its own debris it does have a core of authenticity.

What on earth we are to make of these contradictions, I don’t know. We live in an age of commercial imperatives and of trash fiction trying to ape the prestige of the literary version in order to satisfy the pretensions of the half-sophisticated and slovenly who want to pig out on it. We live in the age of trashmeisters like James Ellroy who want to be Tolstoys, and we live in a so-called ‘age of terror’ that wants to put fear into our souls. Why shouldn’t we have a self-taught novelist with a home-made technique to dramatise the impoverishment of it all?

Comments powered by CComment