- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Custom Article Title: Assassin in the orchard

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Assassin in the orchard

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

As with all forms of Australian cultural activity, it would be easy to inflate local critical endeavour (its novelty, its scintillations, its martial tendencies) and to forget that the history of acerbity is longer than that of our peppy federation. Hundreds of years before Hal Porter carved up Patrick White, critics were pillorying artists with a deftness and wit that can surprise modern readers. Samuel Johnson said, ‘If bad writers were to pass without reprehension, what should restrain them?’ Even a writer as famously suave and tempered as Henry James did not hesitate to wound. Reviewing Walt Whitman’s Drum-Taps in 1865, he wrote: ‘It has been a melancholy task to read this book; and it is a still more melancholy one to write about it.’ Ten years later, George Bernard Shaw began writing the theatre and music journalism that would forever change criticism, and forever change the public’s perception of criticism’s freedom and indispensability. Open any of Shaw’s pages from the next seventy-five years and you will find passages that present-day editors would clamour to publish. Try, ‘I have no idea of the age at which Grieg perpetrated this tissue of puerilities; but if he was a day over eighteen the exploit is beyond excuse.’

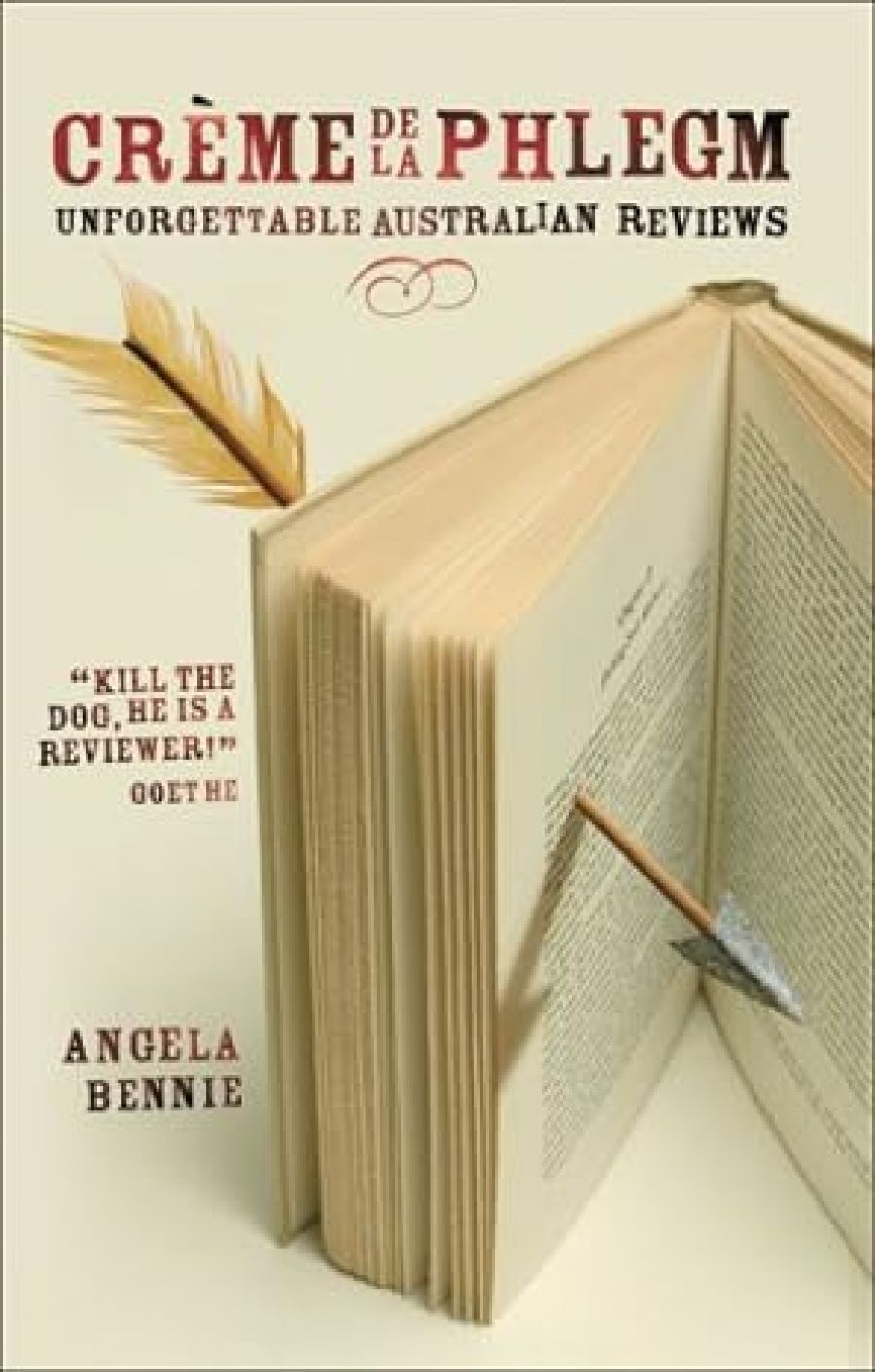

- Book 1 Title: Crème de la Phlegm

- Book 1 Subtitle: Unforgettable Australian reviews

- Book 1 Biblio: Miegunyah, $34.95 hb

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

Now we have a neat compendium from Angela Bennie, herself a former literary editor of the Sydney Morning Herald and a thoughtful critic of the genre, as is obvious from her sixty-page introduction. In her anthology she collects, as the subtitle proclaims, ‘Unforgettable Australian Reviews’ from the past fifty years. (Ignore the odious main title. It could have been worse: one or two working titles did not augur well for the venture. The mucilaginous phrase in fact comes from a review by Gideon Haigh, one of our few authentic scourges, and Bennie simply borrowed it.) Wisely, the editor has not confined herself to the literary world, which is not always as fearless or expectorative as we like to think. The volume also contains ‘famous and infamous’ reviews of theatre, music, film, the visual arts and architecture. Restaurant reviews, always gamey, would have been a piquant addition.

The book opens with A.D. Hope’s notorious review of The Tree of Man, first published in 1956. Hope, like every respectable critic since Shaw, knew the importance of concision and directness: ‘Mr White has three disastrous faults as a novelist: he knows too much, he tells too much and he talks too much.’ Reviews by Robin Boyd and Sylvia Lawson remind us how good Nation was – how good it was for Australian readers – nearly half a century ago. The fourth critic in the book is Max Harris, writing there in 1959, fretful about the state of criticism in this country and on the verge of launching Australian Book Review, in its first iteration: ‘Australia could well do with a journal concentrating on pure literary criticism. By and large criticism doesn’t go much beyond the rudimentary book review. Reputations are built up on bald assertion, stemming very often from the crude “mates together” principle.’

ABR is there, virtually from the start – not always winningly in hindsight, it must be said. Allan Ashbolt, reviewing Martin Boyd’s When Blackbirds Sing in 1963, is wide of the mark (‘Mr Boyd is a trier, there is no doubt about that. But his aims are beyond his abilities’), and the brief, anonymous review of Kath Walker’s We Are Going almost smirks with the tensions and condescension of 1964.

Some of our most incisive critics have been music critics. Charles Higham, writing in 1964, is unimpressed by the touring Beatles, always happier in recording studios than on-stage. Paul reminds him of ‘an attenuated choir-boy with licorice eyes’, while ‘[t]he others looked tired, jaded and old’. (No wonder, when you recall what they got up to at the Southern Cross.) Australian critics aren’t wont to be political, but Bruce Elder is mordant about Midnight Oil, likening them to ‘a kind of antipodean pub rock version of Queen’. Describing them as ‘life-denying, sexist, secular and bigoted’, Elder despises their ‘endless touting of Australia and all things Australian’. Nor does he spare Our Kylie: ‘[W]e realise just how huge Minogue’s mediocrity really is. She can sing – just. She can dance – sort of. She can entertain a crowd with all the dubious panache you would expect from Charlene.’ Writing like this is brave, rare. Nothing is more sacrosanct than the popular, the lucrative, the media-wise.

Readers of The Age and The Australian from the 1960s to the 1990s will remember Kenneth Hince’s music reviews. Hince, our most Shavian critic, never pulled his punches. He knew his stuff and he was unafraid – a potent combination. In 1971 he reviewed a book called Music for Pleasure, by the ABC’s John Cargher, now so venerable and incomprehensible he sounds like the last of the Habsburgs. ‘Of all the books written in Australia about music, it is clearly the worst … Congratulations on a masterpiece of badness, superbly well done.’ Barrie Kosky’s idea of Mozart is anathema to the prescient Hince: ‘With such a talent for muffling beauty, Kosky can hardly fail to forge a brilliant international career.’

Of all the specialist reviewers, the art critics seem to be the most waspish. John McDonald, writing in 1995, had no illusions about the overrated Brett Whiteley: ‘Such vast sums have been invested in Whiteley’s oeuvre that it seems inconceivable there can be so little of real quality, and critics have been making excuses for him for a very long time.’ Else-where, Terence Maloon and Christopher Heathcote are refreshingly unimpressed by Jenny Watson. Going back further, Patrick McCaughey, no devotee of ‘bejewelled jock straps’, lays into the Surrealist painter James Gleeson.

Of the literary reviews, at least one is a tour de force: Gerald Murnane on Holden’s Performance, commissioned for these pages in 1987. ‘Holden’s Performance kept me awake (to put the matter positively) almost to Alphington, which corresponds to a score of three [out of five] on my scale … [The novel] made me laugh many times. Sometimes I put the book down and thought. Never did I feel a deep sympathy with any of the characters.’ A brilliant example of close reading, it also has the rare distinction of stretching the review genre, of doing things differently. Craig Sherborne did something comparably, and deceptively, plain when he stepped up to the block for Dawn Fraser’s memoirs (‘If my Aunty Dorothy had ever dictated a book, it would have sounded just like Dawn’s’). Peter Craven has three reviews, two of them first published here (Robert Dessaix’s Corfu and Elliot Perlman’s Seven Types of Ambiguity): brilliant examples of the excoriating art.

As with all anthologies, we miss some favourites. High on the list is Clive James, one of the finest critics this country has produced, in literature or television. The editor tells us that ‘many critics were not prepared to see their negative critiques exhumed for a second look’. It is difficult to imagine James, hardly a chary writer, declining this opportunity.

We tend to exaggerate the number of severe reviews. ‘Critics are like bees,’ wrote Randall Jarrell, fine poet and critic; ‘one sting lasts longer than a dozen jars of honey.’ Good critics yearn to discover great art. As Dryden said in 1668, ‘They wholly mistake the nature of criticism who think its business is principally to find fault.’

Wholly mistake it, though, they doggedly do. Few artists can match Katharine Hepburn’s insouciance (‘I never cared what anyone wrote about me, as long as it wasn’t the truth’). Writers have never been comfortable with the critic: ‘the assassin of my orchards’, as Frank O’Hara wrote in a poem. Verdi’s more sanguinary operas (Attila or Macbeth, say) seem mild by comparison with the wrath of the vengeful artist. Some authors and publishing lions discourage openness with their tedious umbrage and recriminations. Despite what the divas and divos think, the proportion of negative reviews is small. There are many reasons why reviewers pull their punches: timidity, conformity, professional nervousness or self-preservation, respect for the artist’s earlier work, dislike of causing hurt, even goodness, improbable as it seems. Criticism’s influence can be exaggerated, its conservatism and imperfections overlooked: the creeping brevity; the apotheosis of the popular; the dreary ‘profile’ industry; the cosseting of certain reputations. Meanwhile, the blurring of promotion and criticism has a vitiating effect.

So will this book help the cause, lift standards, raise consciousness? Is it unforgettable? Maybe not. But the anthology preserves some of our best and feistiest critical writing – in a country not very good at doing that. It is salutary to reread many of these reviews and to reflect, in this dubious age of publicity, that the function of criticism is not to pamper, placate or generally pussyfoot around – but to tell a kind of truth, and, yes, occasionally to scorch.

Comments powered by CComment