- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Reference

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: More treasures

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

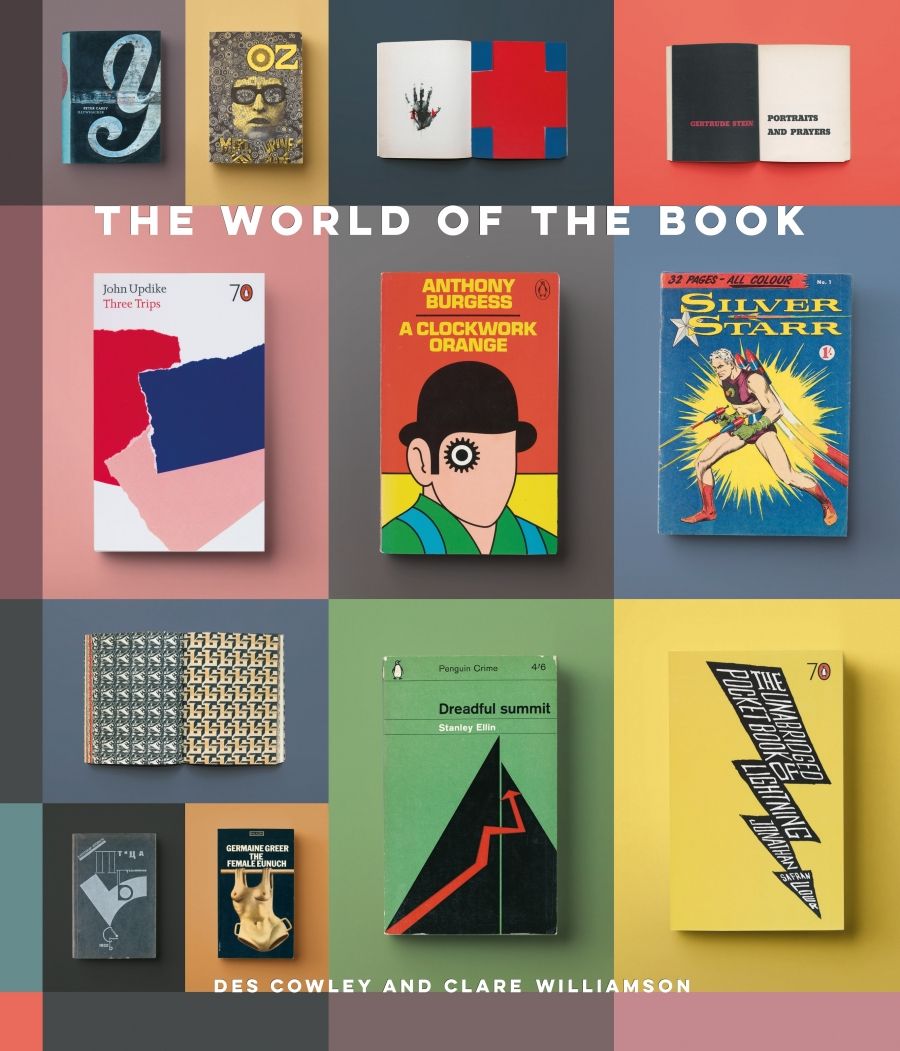

The World Of The Book is an offshoot of the State Library of Victoria’s permanent ‘Mirror of the World’ exhibition, which uses major works from the SLV’s collections to present a global history of books and ideas. The exhibition itself is a testament to the depth and diversity of the SLV’s collections, and the book is thus part exhibition catalogue, part ‘Treasures’ book.

- Book 1 Title: The World of the Book

- Book 1 Biblio: Miegunyah, $59.95 hb, 247 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/5bGyv1

The SLV has done books of its treasures before, most recently in 2003, the same year that MUP published Treasures: Highlights of the Cultural Collections of the University of Melbourne, as part of the university’s sesquicentenary. Institutions usually produce such books as part of long-term strategies to secure a presence in the cultural landscape; if they make any kind of financial profit in their own right, that is a bonus. In that sense, Treasures of the State Library of Victoria was an embarrassing failure; with its overly busy design and lightweight text, produced on commission by a corporate vanity publisher, it did the institution no justice. As both an exhibition catalogue and a cultural monument, The World of the Book is everything that Treasures was not: erudite, engaging, unpretentious and a visual treat. As a summary of the entire history of books and ideas, produced by two individuals, it is awesomely comprehensive. It is a popular introduction rather than a scholarly reference, but, in a remarkably short space, Des Cowley and Clare Williamson succeed in conveying all the essential facts, and many more quirky and enlightening ones, about the history of books and reading. There are some bloopers (two references – one might have been regarded as a misfortune – to ‘Sir Thomas Elyor’ [i.e. Elyot]), and it would be easy to quarrel with the list of further reading (no mention, for example, of UQP’s History of the Book in Australia series, which Richard Walsh discusses elsewhere in this issue; but for a book of such ambitious range, the flaws are trivial and few. As a practitioner of book history, I am deeply jealous.

The potential audience for The World of the Book is huge: anyone with an interest in books and reading. A sign of the publisher’s confidence is that, unlike most Miegunyah titles, this one has no limitation statement (the university Treasures had a print run of 1750). It will keep selling for years, whether the SLV maintains the ‘Mirror of the world’ exhibition or not.

The book is divided into four parts: ‘Books and Ideas’, ‘The Book and the Imagination’, ‘Exploring the World’, and ‘The Artist and the Book’. The weakest, most perfunctory writing is, unsurprisingly, in the wider-ranging overview chapters, the ones that had to be there but which no one was really excited about. ‘Literary Foundations’ offers a tour of the monuments of world literature in half a dozen pages. Cowley and Williamson have gone as far afield as Dublin’s Chester Beatty Library to source their illustrations, but their selection of literary highlights clearly was defined to a large extent by the strengths and limitations of the SLV. Das Narrenschiff (‘the ship of fools’) gets a Guernsey; Goethe’s Faust does not. The writing jumps around, betraying its origins in exhibition labels: concise, factually accurate, just right for a display case, but (ironically, given the subject matter) dissatisfying in a book.

The more in-depth chapters, though, are very good indeed. The chapter on Kerouac, Ginsberg, Burroughs, et al., is a little gem. Cowley, an enthusiast of the Beat writers and the jazz music that inspired them, makes a brief but compelling case for their artistic merits as well as their significance as participant observers of a key moment in the evolution of Western culture. Similarly, the chapter on contemporary artists’ books opens up a specialist field to a general audience with pithy, evocative writing: Bruno Leti’s masterpiece Iron age (1996), a series of images printed from scraps of rusted farm machinery, is summarised by Cowley and Williamson as ‘a meditation on randomness and time, an excavation of the ages’.

In the 1880s knowledgeable visitors thought the Melbourne Public Library, as it was then called, superior to the New York Public Library. Its growth stalled in the twentieth century, and it was overshadowed by its counterparts in Sydney and Canberra. The World of the Book reminds us that it nonetheless remains one of Australia’s great cultural institutions.

Comments powered by CComment