- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Society

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

From the horror of ‘traumascapes’ – the eponymous subject of Tumarkin’s first book (2005) – to the noble quality we call courage is one of those small steps that equate to giant leaps. Having spent a long time thinking and writing about the devastation caused to particular sites during the harsher episodes of recent history, Tumarkin has moved on to the human sentiments associated with those acts. Courage is not the only one, but because it appears so positive and universal it is a prime subject for interrogation, even deconstruction. (Yes, Maria, I know this is the theory-speak you disdain, but like the language of science, its vocabulary can lead to clarification as well as obfuscation.)

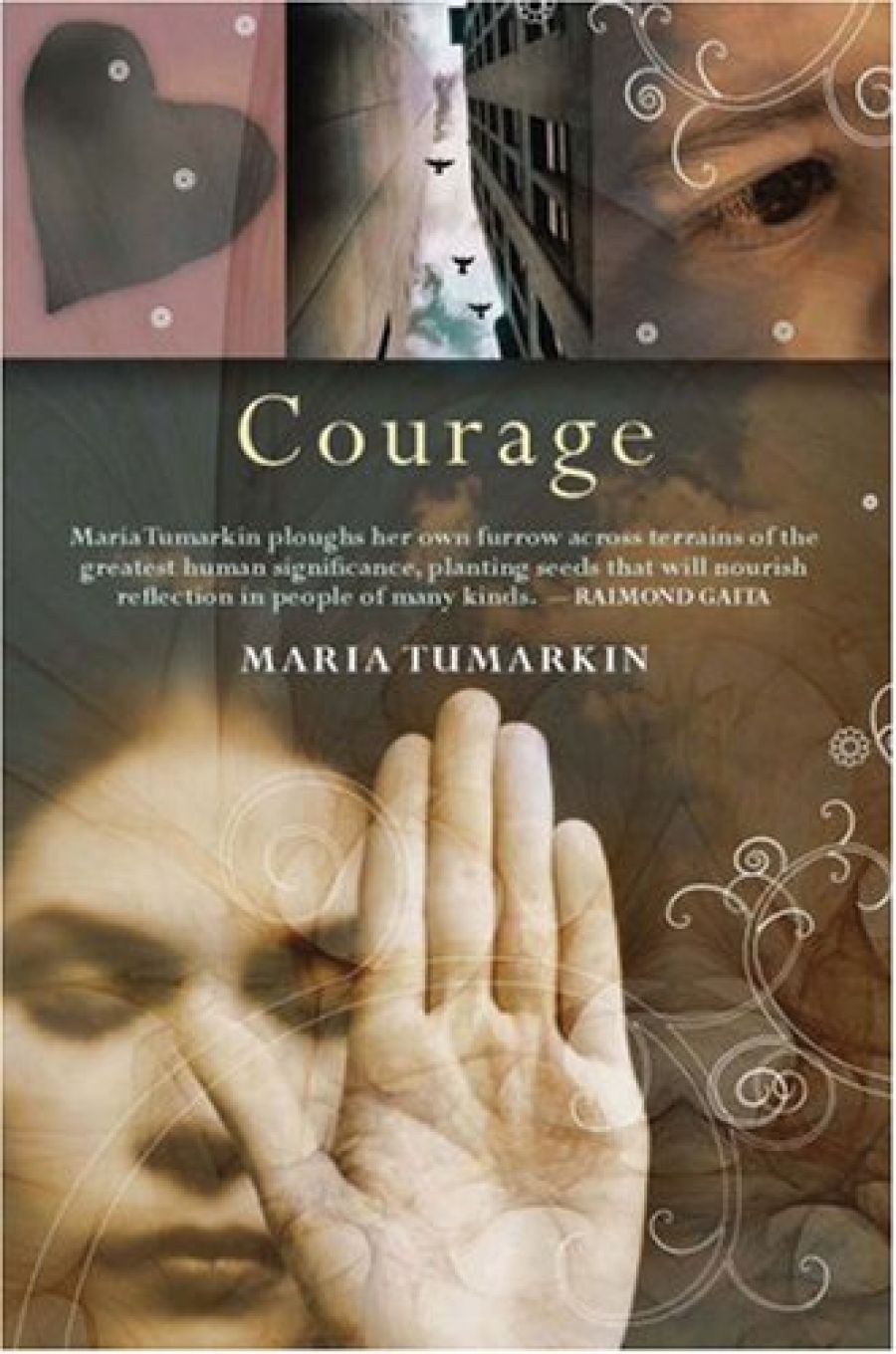

- Book 1 Title: Courage

- Book 1 Biblio: MUP, $32.95 pb, 244 pp

Nevertheless, this book is not just a sequel to a published PhD. Courage, the quality, has been the author’s obsession since early adolescence. Exploring it in a ‘traditional monograph’, however, as a mere interested observer, turned out to be an unsatisfactory process. Tumarkin borrows from author Dave Eggers to explain that it was ‘like driving a car in a clown’s suit’. The simile does not strike me as particularly apt, but it gave her the confidence to insert segments of her own biography (read feelings, fears, passions and prejudices) into the discourse. The result, as in Traumascapes, is a discussion that zigzags from colourful illustration to personal revelation, from touching vignette to belligerent polemic, reference to riff, literature to philosophy. As with a modern ’zine, the variety and brevity of the bytes ensures that you do not get bored with any one topic, and if there is no sustained argument, you accept that this is a deliberate strategy. Courage, of its very nature, is fragmented, subjective, individual, impulsive, layered, kaleidoscopic. How could it ever be served by a cautiously reasoned ‘on the one hand this, on the other that’ (Tumarkin’s most despised procedure)?

This narrative is therefore darting but not haphazard, especially as there are chapter titles to act as signposts. Yet there is still something odd going on. The headings subvert their signalling role by avoiding capital letters and hiding between square brackets – e.g. ‘[the migrant]’, ‘[an open-door policy]’ – as if to convey a covert message. One chapter is supposed to be on ‘Fear’; but it also encompasses migrant English, the ‘toxic dump’ (Melbourne University), an interesting young man, the dubious value of arts degrees, satire, Zadie Smith’s novel On Beauty (a brief but excellent analysis), the contents of both Tumarkin’s and Fay Weldon’s wombs, and the author’s admiration for Eggers’s A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius (2000). Are the brackets inserted in order to enclose a contents prone to spilling over and going everywhere, to allow for an authorial voice which wants it not just both ways but every which way? To please and not to please. To stick it to the reader with this-is-how-I-am-in-your-face-isms, and in the next breath to speak from a heart that parades valour, honesty, love, intelligence, wit, sharpness and, above all, a gritty willingness to be sliced open. This last is a principle rather than an affect. Describing a singular essay on husband-envy published by Kathryn Chetkovich, the honest but less successful writer-wife of Jonathan Franzen, Tumarkin writes: ‘She is not baring her soul in order to obtain absolution or attention; her soul, both as a woman and a writer is being shaped, slowly and painstakingly, through this act of uncompromising selfexposure.’

Soul-baring plays a brilliant and confronting role in Tumarkin’s book, and probably in her soul, too. Just as she was seized with admiration for Chetkovich, so does Tumarkin provoke, persuade and prescribe reaction in her own readers. She knows that no one entering her force-field will fail to look back over their own record of courage and weakness, with a remorseful nod in the direction of Shakespeare’s line about what conscience does to us all.

But Tumarkin would surely be the first to acknowledge that courage is something we can only do according to our own convictions; in fact, she makes the point through her own Helen Demidenko story. As a student savagely scornful of the language of moderation, she elected to shock a Soviet history tutorial with an outrageous outburst: ‘It is great ... that the whole Demidenko saga has happened,’ she announced. A Demidenko could say what a ‘Waspy’ Darville could not, thus pointing to a major difference between migrants and the establishment. In the tutorial, Tumarkin herself only escaped ‘total vilification’ because she was a ‘Soviet Jew from Ukraine, the exact target of Demidenko’s literary loathing’.

Yet Tumarkin was not the only one to be singed by that affair. Anyone who did not read Darville’s novel as an antiSemitic tract had to be either courageous or foolhardy to admit this out loud, so punitive was the climate at the time. Foolish enough to let my reading of it be printed in a newspaper, I found my once-friendly Jewish neighbour crossing the road to avoid me, after hissing her opinion that I was unfit to hold my academic job. The lecturer from the Soviet history course publicised his vituperation in a letter to the editor, twisting my position out of recognition in the process.

I would argue that Tumarkin’s book exemplifies an authorial voice that urgently demands a serious, no-holds-barred dialogue with her reader. The intense energy that charges through her explosive and passionate treatise neither tolerates nor deserves a lukewarm response.

Comments powered by CComment