- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

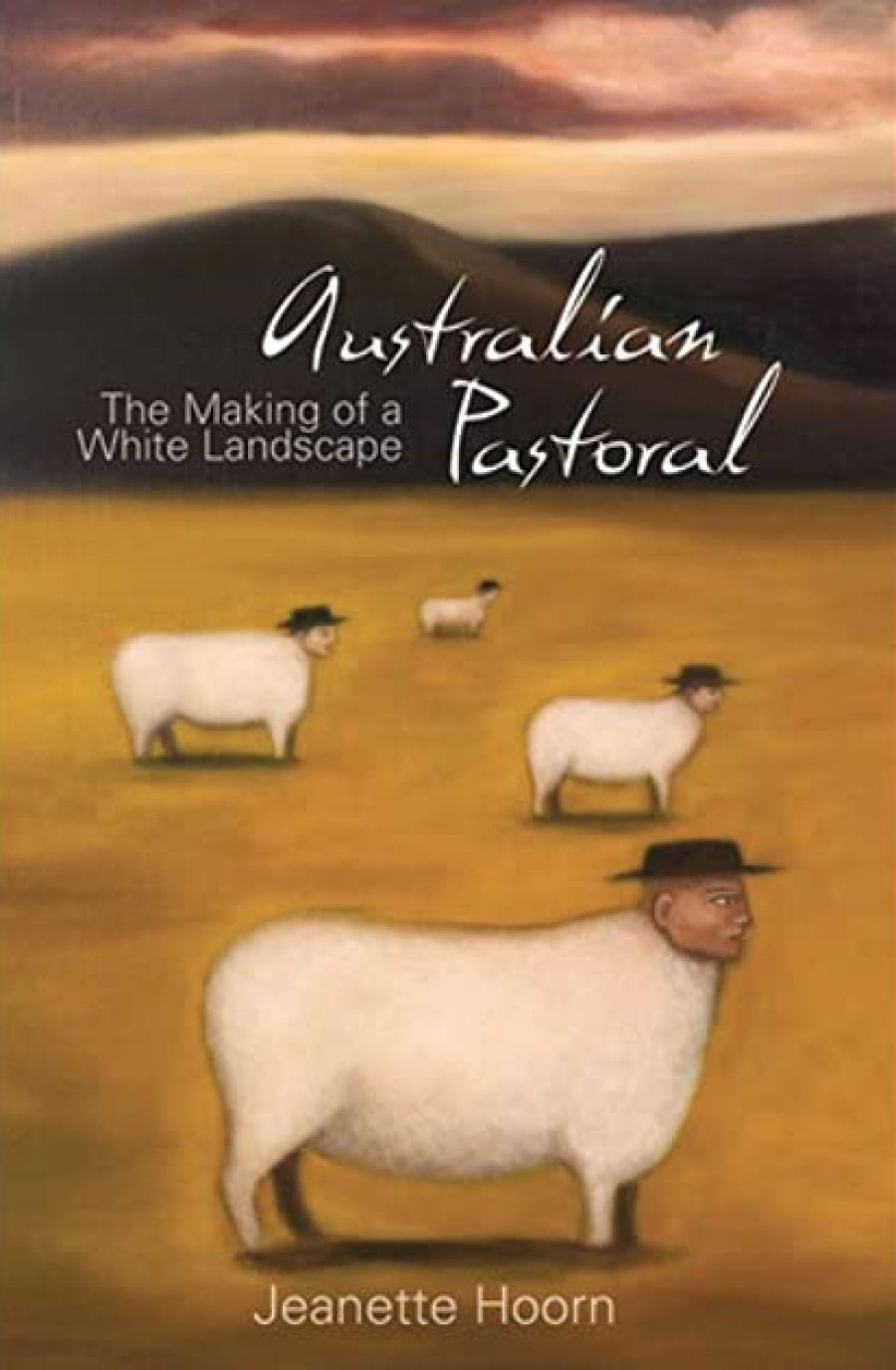

First impressions are unfavourable. The cover is ugly, and too cute: human-headed sheep, male and female, wait motionless for a drought to end while wearing prime ministerial bush-visit hats. We have read Frank Campbell’s rebuke in the Australian: the author Jeanette Hoorn did not know a fox’s tail from a dingo’s. Inside, however, there is a cheering profusion of illustrations, placed in unusually reader-friendly closeness to the relevant discussion, and they include a feast of the best Australian paintings. There are some interesting sources in English eighteenth-century art and, much less familiar, some parallels in German fascist art.

- Book 1 Title: Australian Pastoral

- Book 1 Subtitle: The making of a white landscape

- Book 1 Biblio: Fremantle Press, $29.95 pb, 304 pp

The pastoral mode in classical and Renaissance art pretends that minding sheep and goats and cattle is so easy and undemanding that shepherds have time to play and dance with nymphs. Though Hoorn ignores it, one of John Glover’s largest canvases, Mills’ Plains, Ben Lomond … in the distance (1836) is a warm-hearted Aboriginal ‘pastoral’. Hoorn allows that in around 1890 outer-suburban Melbourne landscapes by Arthur Streeton and Tom Roberts, depicting young people at leisure, are consciously ‘pastoral’. But her principal concern is ‘pastoral capitalism’, the large-scale wool-growing from which, for a century and more, Australia gained most of its wealth. Cattle-grazing fails to interest Hoorn, which perhaps explains why she doesn’t include the work of Sidney Nolan. His wonderful drought carcases of cattle (1953) could have been presented alongside eroded drought landscapes – similarly undiscussed – by Russell Drysdale (1945).

Hoorn approves of Drysdale for his multicultural humans, not only Aborigines but also Japanese pearl divers and country-town Greeks. Two token paragraphs on almost the last pages state that ‘Pastoralism brought serious degradation to the lands and rivers of the continent and record rates of animal extinction …’ Too late. Halfway through we had begun to fret about the absence of eco-awareness. What about the sudden withdrawal around 1890 from over-extended sheep-grazing lands? What about rabbit plagues and cloven-hoofed issues, as well as the issues of peculiarly Australian climates and soils that Tim Flannery has popularised? Hoorn apparently belongs to a pre-Eco-Fright generation, concerned almost exclusively with postmodern analysis of cultural oppression, especially of colonised indigenes. Culture seems more worthy of discussion than does nature. On culture, Hoorn can be too conventional, but at other times she presents very interesting detail. For example, from first colonisation and land-taking (c.1790) she identifies a ‘Spearing Quintet’ of little-known watercolours. There had been an act of Aboriginal resistance: the spearing of Governor Phillip, almost certainly with intent to kill. Phillip subsequently negotiated with Aboriginal leaders. He may have recognised the significance of the moment, and commissioned from an unidentified artist these primitive little history paintings, to send to London as a record of a kind of treaty.

The Virgilian ‘Georgic’ mode, concerned with planting crops more than minding ‘Pastoral’ animals, receives attention, notably in S.T. Gill’s earliest South Australian watercolours. They are where Hoorn came to grief between the fox and the dingo. Neither Frank Campbell’s critical review nor her own spirited comeback in the Australian noted the discrepancy between dates in her text and dates in her editor’s or publisher’s picture captions. The captions give c.1847, the text 1841–43, and Hoorn’s first report of a fox in Adelaide in 1845. Her own dating undermines her rebuke to White Australia for the unwelcome import of foxes.

It is only one example of a slightly dyslexic air throughout the book. Another self-contradiction is Tom Roberts’s Shearing the rams (1888–90), painted ‘in his city studio’ on one page, partly on the spot elsewhere. Too many names are misspelt (F. G. Dalgetty, Immants Tillers, E. Philipps Fox, Neil Black, Charles Summer, Claude Lorraine, Kenneth Clarke, Prince Phillip) or given in an unaccepted form (Lady Jane Franklin, Walter Baldwin Spencer, James MacDonald). So are art terms (picture ‘plain’). Australianisms are misused: Shearing the rams is not an ‘outback’ subject (Corowa on the Murray is ‘inside’ country); Eugene von Guérard’s Keilor landscape is not out in the woolgrowers’ most favoured Western District of Victoria but close to Melbourne airport. Hoorn’s grip on rural matters is shaky: hand-threshing of wheat was done with a flail, not a scythe. And just when did we begin to call our graziers and squatters ‘pastoralists’, and grazing ‘pastoralism’? (Probably the 1880s.)

Never mind. Hoorn’s ‘pastoraphilia’ is an inspired coinage for the loopy early-twentieth-century discourse that she swipes at in her penultimate chapter. In ‘A Pastoral Cult: Social Darwinism and White Supremacism’, we meet the fascinating but relatively unfamiliar James Collier, author of The Pastoral Age in Australasia (1911). Collier leads to J.S. MacDonald, director of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, who in 1931 notoriously endorsed paintings like Streeton’s Land of the Golden Fleece (1926): ‘They point the way to which life should be lived in Australia, with the maximum of flocks and the minimum of factories … If we choose we can yet be the elect of the world, the last of the pastoralists, the thoroughbred Aryans in all their nobility.’ Hoorn skewers silly white men well.

Comments powered by CComment