- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

It is usually sports fans and politicians who are uncharitably accused of being biased. The new British prime minister, Gordon Brown, is literally one-eyed. He was blinded in both eyes in his youth as a result of an accident playing rugby. Part of the treatment for his blindness required him to lie still in a darkened room for six months. It half worked, and he recovered his sight in one eye. Asked about this experience some years later, Brown said that he had felt ashamed, lying there doing nothing, when the only thing he had wrong with him was that he had lost his sight. This sounds Scottish Presbyterian (which he was) and stoical, which he must be to have survived eleven years as heir apparent to the ebullient Tony Blair. Brown and his predecessor are very different kinds of men. The Conservative MP Boris Johnson captured some of these differences in an article in the Spectator, in which he referred to Blair’s humour and ‘passion with a sense of optimism’. With the arrival of Gordon Brown, ‘a gloomy Scotch mist has descended on Westminster’.

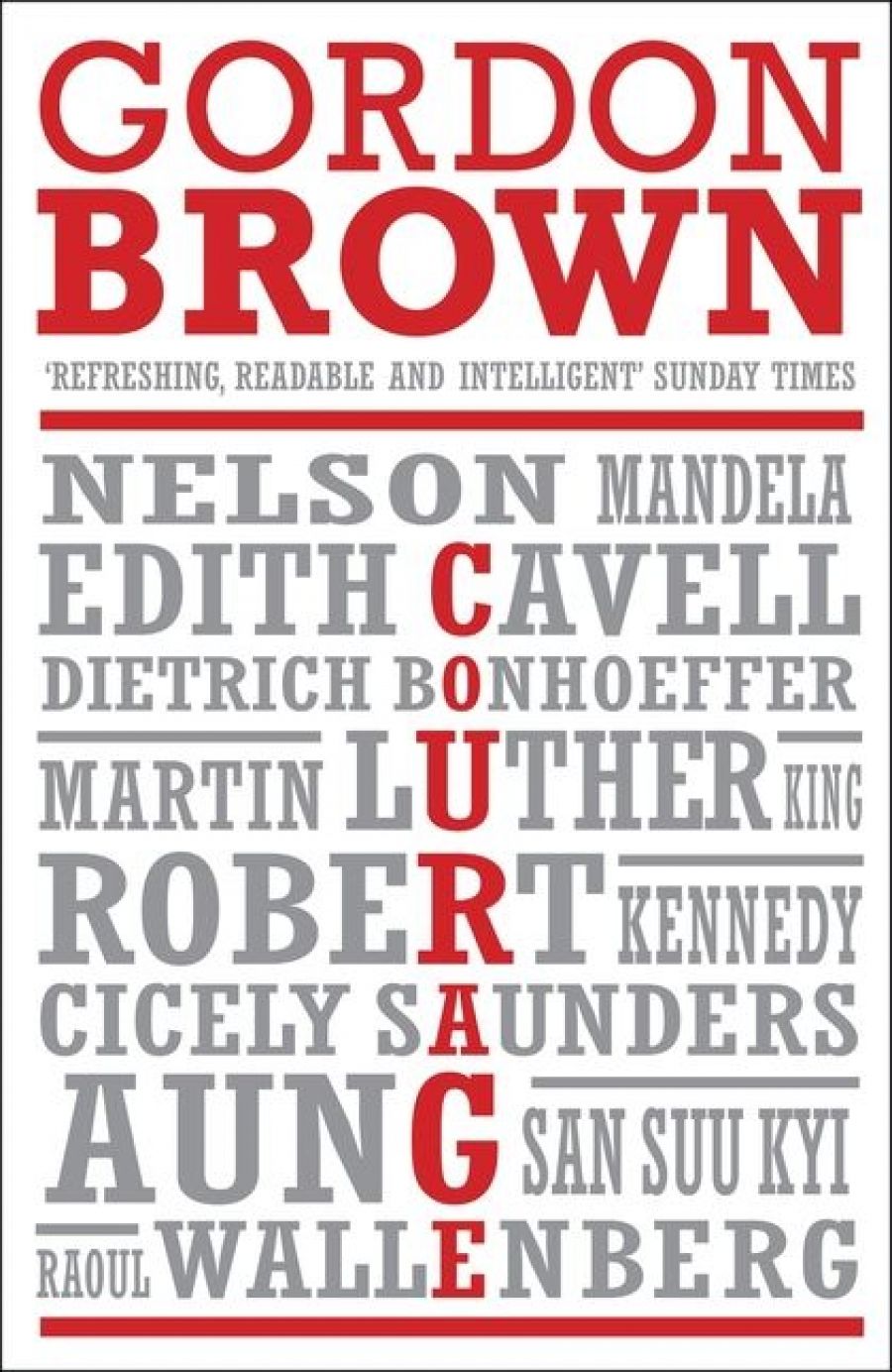

- Book 1 Title: Courage

- Book 1 Subtitle: Eight portraits

- Book 1 Biblio: Bloomsbury, $49.95 hb, 274 pp

There is a thin blurred line between stoicism, strictly a philosophy, and courage, which suggests a particular act or course of conduct. Stoicism can, of course, be displayed in the ability to bear pain and adversity with fortitude. According to Winston Churchill, who has become a sage on certain matters, ‘courage is the first of human qualities because it is the quality which guarantees all others’. This surely depends on circumstances, but nonetheless the quotation seems important to Gordon Brown, who has written a book called Courage: Eight portraits, in which courage is a discernible virtue that manifests itself in many different ways.

Brown writes that ‘as far back as I can remember I have been fascinated by men and women of courage’. He tells us that at the age of ten he was given an encyclopedia of history in which ‘great deeds were recorded’. So the book is really about heroes or great human achievers. Courage becomes the generic quality that pulls it all together.

It is difficult to understand why Gordon Brown should write a book of this kind. Is it really a book about his eight subjects, or a book about him? It tells us about the people he admires, and one is tempted to assume that some of their qualities have rubbed off on him. And this may be so. Another book edited by Brown, Values, Visions and Voices: An anthology of socialism (1995), tempts the reader to a similar conclusion, in a more persuasive way, about the values of the editor.

John F. Kennedy, another successful politician and man of destiny, wrote a similar sort of book called Profiles of Courage (1956) about his particular heroes. All American, they included two not very successful presidents and half a dozen politicians of the swash-buckling variety. This book won the future president the Pulitzer Prize for history.

Brown’s book, published at the start of his term as prime minister, is much less parochial. Only two of the eight subjects (both women) are British; the rest are from various countries. Only one, Robert F. Kennedy, might be described as a professional politician.

They are an eclectic lot, Brown’s subjects. Edith Cavell, a British nurse working in German-occupied Belgium during World War I, helped a large number of escaped British prisoners to reach the French frontier and ultimately Britain by means of an underground network. For this she was subsequently executed by the Germans. Cicely Saunders’s great life work was really as the founder of the hospice movement, which changed the way that society cares for the dying. Her courage was the courage of her convictions, battling with the conservative attitudes of the established medical profession. The other subjects – Nelson Mandela, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Robert Kennedy, Martin Luther King, Raoul Wallenberg, and Aung San Suu Kyi – are better known, and certainly have been more frequently written about.

Mandela, arguably the moral hero of the twentieth century, fits easily into an anthology of this kind. But the things that make him a hero are many: wisdom, compassion, humility and, of course, courage. Aung San Suu Kyi is an example of someone who gives up, in the interest of her great cause of democracy in Burma, ‘more comfortable and far less dangerous alternatives’. Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Martin Luther King were both driven by Christian faith to oppose racial inequality and persecution. In Bonhoeffer’s case, the persecution and terror was against the Jews in Nazi Germany. In King’s case, as leader of the civil rights movement, the discrimination was against black Americans in the South. Wallenberg, the Swedish aristocrat turned diplomat, embarked on an heroic and inventive campaign in Budapest in 1944 to save Hungarian Jews from transportation to the Nazi death camps. His life seems to have ended in a Soviet prison.

Robert Kennedy seems a strange choice for inclusion in this book. The scion of a wealthy family, and a prince of the Kennedys’ Camelot, nothing that he did in his life suggests deprivation or suffering. This is the same Kennedy who worked so enthusiastically for the Un-American Activities Committee of Senator Joseph McCarthy, who, as attorney-general, authorised the FBI to tap the phone of Martin Luther King, and who was a late, if highly effective, convert to the cause of the civil rights movement. ‘Tough’ is an adjective more associated with Robert Kennedy than is ‘courageous’. According to Brown’s portrait, an aspect of Kennedy’s courage was to change the political debate by ‘what he called “numerous, diverse” acts of initiative and daring’ towards empowerment of citizens and the development of the idea of community. That he began to espouse these ideas nearly thirty years before they were embraced by New Labour in Britain is interesting, but not necessarily courageous.

Brown’s research assistant, Kathy Koester, has been diligent in digging out snippets of information which may not have appeared elsewhere. She talked, for example, to a former parishioner of Bonhoeffer, who gave her some interesting information about his time as a pastor in London. She also interviewed Wallenberg’s half-sister, who told her that in 1942 she and Wallenberg saw the movie Pimpernel Smith (1941), in which a university professor, played by the great British actor Leslie Howard, outwitted the Nazis and rescued Jews from Germany. Later, Wallenberg said that he wanted to do something like Pimpernel Smith. In a gracious acknowledgment of the assistance that he received in preparing this book, Brown writes, ‘I have used many secondary sources, some great studies of the individuals I have portrayed …’

The problem with these eight portraits is that they are not ‘great studies’. To earn that description they would need to contain more original insights, be less reliant on secondary sources and be better written than they are. Courage will, however, be a useful reference book for readers seeking information about the various subjects. Another use might be as a gift from a stern father to a teenager he believes to be running off the rails. Read this and it will make a grown-up of you – if you follow these examples.

In fairness, it should be added that, of the eight subjects of the book, two were executed, two were assassinated, two have spent a large part of their lives in custody (Mandela and Aung San Suu Kyi) and one probably died in a Soviet jail.

John Button will have bio

Comments powered by CComment