- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In her other life, Judith Bishop works as a linguist. A passionate concern with the intricacies of language, with the visceral effect of words on the tongue, aurally, and as they are knitted and unravelled on the page is manifest in her first collection of poems, Event. These poems are deeply immersed both in a complex observation of, and engagement with, the natural world, in particular with the ways in which poetic language can intervene in the world of perception, experience and desire. ‘You have to lean and listen for the heart / behind the shining paint’, Bishop writes in ‘Still Life with Cockles and Shells’, which won the 2006 ABR Poetry Prize and which Dorothy Porter included in The Best Australian Poems 2006. Like the beautiful illusions of the still-life painting, Bishop’s poetry creates an aesthetic surface which mimics the stasis of death and also harbours the ‘flutter in its flank’, the pulse of possibility visible to the attentive reader–observer. Look closely, her poetry exhorts, yield to the currents of language and image, become witness to death and life in intimate and endlessly renewing ‘events’ of struggle and embrace.

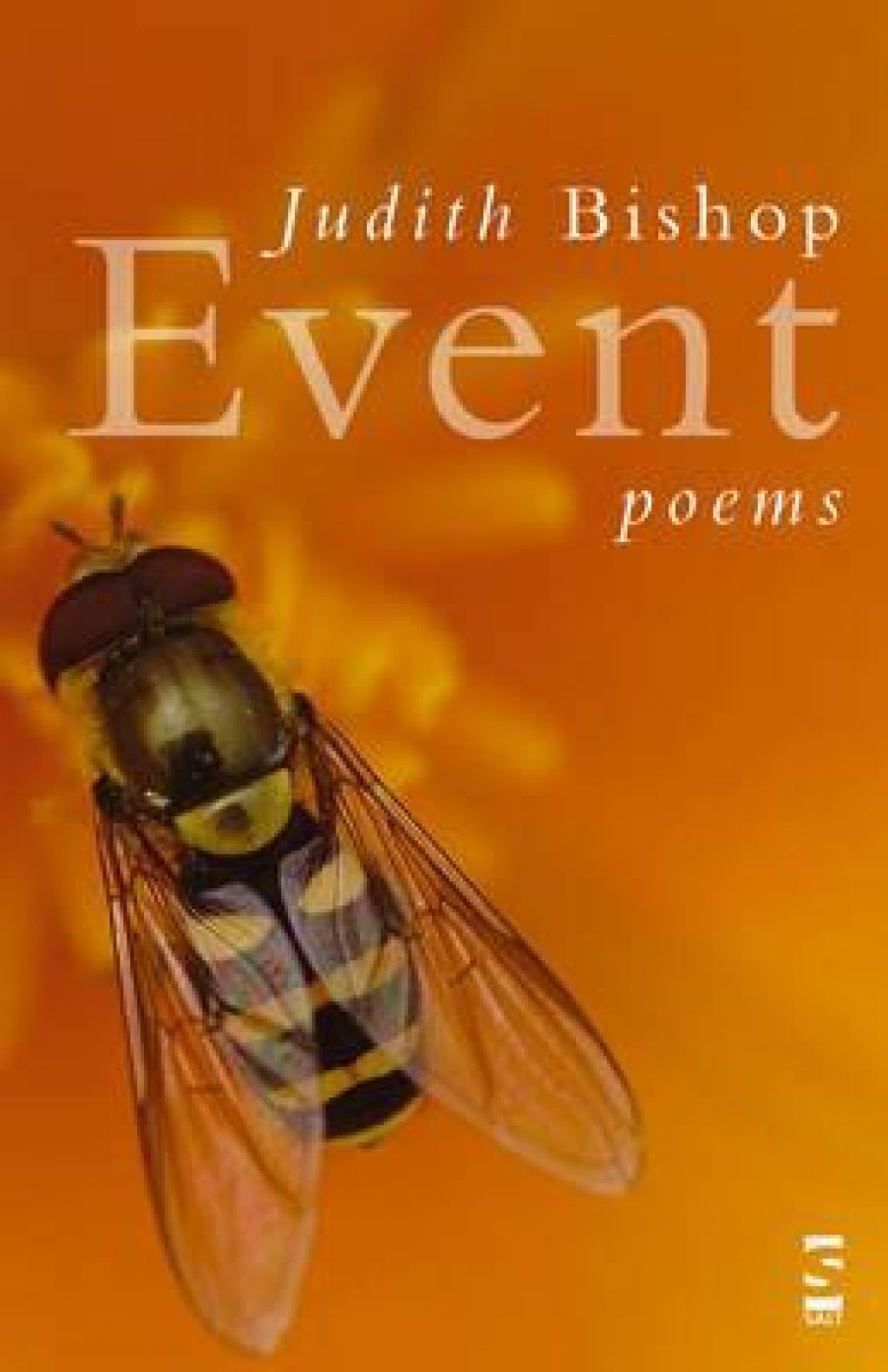

- Book 1 Title: Event

- Book 1 Biblio: Salt Publishing, $24.95 pb, 84 pp

Event demonstrates the assurance of a poet coming into the fullness of her powers, confident in exploring a range of topics and styles. The collection makes use of different poetic forms: the short lyric, the prose poem, the dramatic form, poems which fracture lines across the page, poems which spin their lines out into almost narrative length and complexity, others which clip them closer into a discipline of metaphor and brevity. The opening poem, ‘After the Elements’, draws us into a vortex of energy. We are pulled along by the force of enjambment and by the inextricability of the antithetical elements, which are always just behind, disappearing into the poem’s past:

neither moves inside the wilder air –

those bands of warm and cold, force

and impetus or null

that comes when two great streams oppose

and cancel out; we are

too far from water now, both you and I.

Like the heartbeat latent in the still life, the poem both recognises and draws out the breath from the ‘sandstone’ of the past; in this sense, it is a poem about the poem’s own originary moment, the elemental swirl that gives birth to the shaping, almost breathless, imagination of the poetic form.

The sequence of poems about Doña Marina, the Aztec woman who was the lover and translator of the Spanish conquistador Cortés, offers another kind of window onto Bishop’s interest in the dialectic between self and other, and, in this case, between language, power and agency. These poems, spread throughout the collection, show the slipperiness of any ‘story’ and the inevitable partialness of any point of view. We hear a ‘first’ and ‘second’ voice which offer different commentaries and perspectives upon Marina, especially as she is hauled through multiple translations, from her native Nuhuatl, to Mayan and to Spanish: ‘Hear her: she is breathing. / Breath in , Nuahatl; / breath out, / Maya. / Hair flails from her mouth …’ In addition, we hear the voices of Cortés himself, both eroticising and objectifying, and of Moctezoma, the Great Speaker. We hear Marina’s own voice – introspective, retrospective, self-justifying, self-pitying, desperate, creative in her efforts to survive and even thrive. All these juxtaposed, sometimes conflicting, sometimes fractured voices that cannot communicate with any other, focus the question of how to view or read Marina. Is she a victim of the dominant power of the Spaniard, and to what extent is she complicit in the violence visited upon her own peoples through her linguistic and sexual alliance with such a figure of power? The interspersed, undercut words of the various ‘personae’ draw us, through a web of word and image, into the philosophical sphere of epistemology, of how we might know anything and of how words might mask and/or reveal. As Bishop puts it in the poem ‘Alice Missing in Wonderland’, ‘Tread carefully. / Consider what’s left out’. The gaps in the story, the images left unrepresented are easily as potent – and as dangerous – as what finds its way into the explicitness of language.

The idea and experience of indeterminacy, of finding one’s self between positions of apparent stability – knowing/not knowing, living/dying, watching/engaging – is repeatedly evoked in Bishop’s work. Whether it is the tapping, ‘nearly not a sound at all’ (‘It Begins Where You Stand’), which spawns the tornado, or the incipience of ‘clouds distended by a rain / unfalling always’ (‘Affair’), or the image of the ‘heart, arrested muscle’ (‘The Heart, Arrested Muscle …’), the moment of falling is always aligned with death, that stepping into the unknown, or what she describes in ‘Still Life with Cockles and Shell’ as ‘the night / after Apocalypse’. However, using the images and perspectives of the neo-pastoral, Bishop often images this hiatus in terms of the natural world. ‘Birds / articulate death better’, she notes in ‘The Heart, Arrested Muscle …’; they ‘never see death coming: / it observes from their eyes / as they knit / faultlessly, the cumulus to mud’. This poem – emblematic of Bishop’s work – begins in the possibilities of the title’s ellipses; the poem is as much a making as it is a dissolution, an event of the linguistic imagination arrayed between the airiness of flight and the final suck of mud.

Comments powered by CComment