- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Behind Philip Jones’s Ochre and Rust: Artefacts and encounters on Australian frontiers are many books about the interaction of settlers and indigenes. Writers relevant to this book include the museum curator Aldo Massola (writing in the 1960s and 1970s) and retired archaeologist John Mulvaney (writing in the 1980s and 1990s). Massola brought out objects and archival material from the Museum of Victoria, writing their stories for a tourist or localhistory readership. He was a pioneer whose work is no less valuable for presenting an undifferentiated mix of hearsay, intuition, document, object, science and human observation. Although he rarely named his sources, they exist for most, if not all, of what he said so lightly.

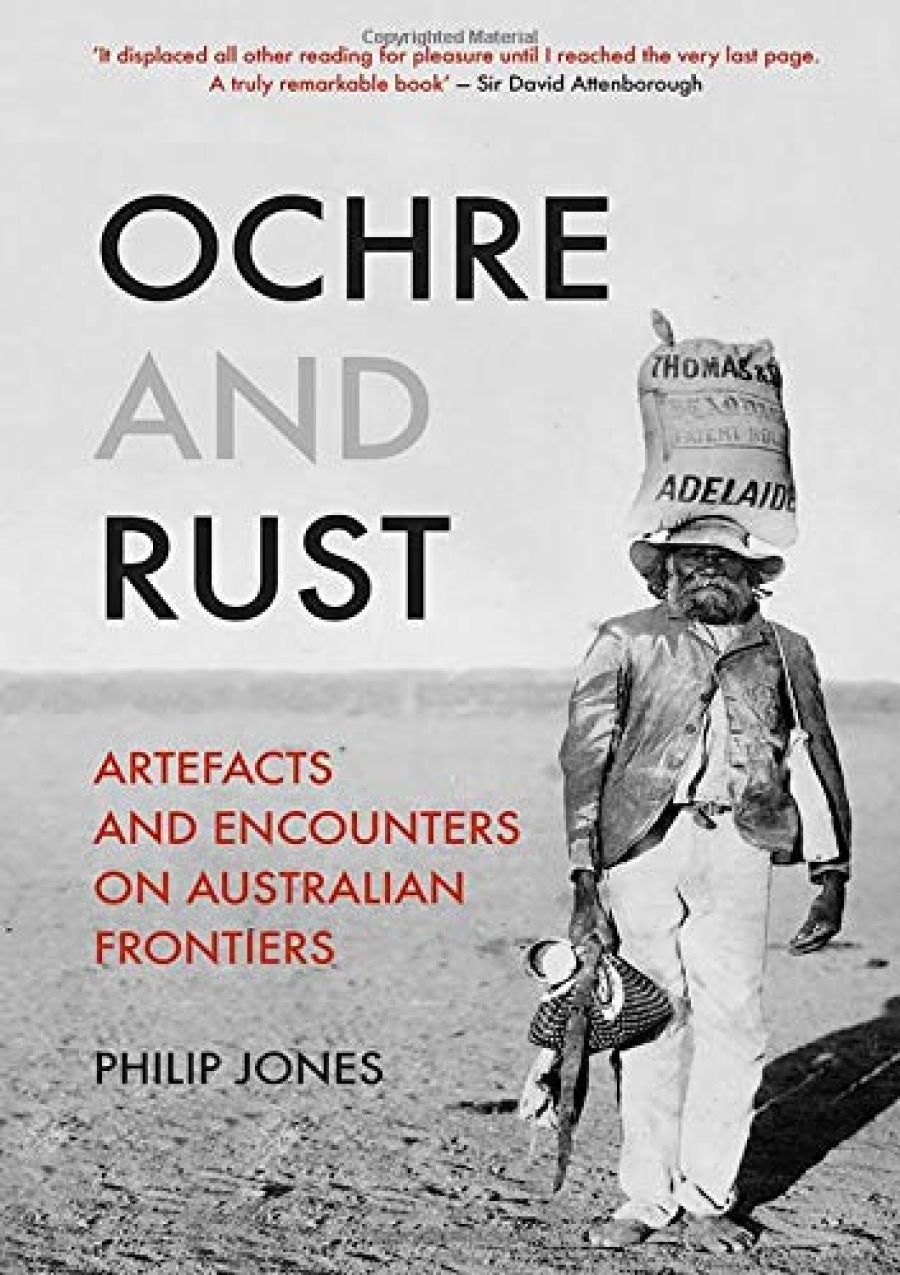

- Book 1 Title: Ochre And Rust

- Book 1 Subtitle: Artefacts and encounters on Australian frontiers

- Book 1 Biblio: Wakefield Press, $49.95 hb, 446 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/n9dk7

At the other extreme, Mulvaney’s dry yet gripping historical narratives are firmly disciplined. Basing much of his work on editing old texts, he has managed to write movingly about the human complexities of frontier life. In general, Ochre and Rust conforms to the best of the tradition while marking a significant departure. Jones is not in Mulvaney’s secure position of usher; on the contrary, one has a sense of Jones coping with the occasional gaping hole in the evidence. Nor does he have Massola’s freedom to write unconstrainedly. These days the historian is under considerable pressure to represent figures from the past as co-players in the text. As a result, the authoritative voice has gone from much history writing. Jones breaks from unity, not willingly perhaps, but as a consequence of maintaining a concept of rectitude that valorises the written report over other kinds of information. His solution to the problem of how to add his point of view to the past record has been to draw a line within the scene of each story, beyond which our vision is unclear, and with exemplary clarity to show that such demarcations in cultural imagining do exist. Shadowing the past in this way, he tacitly acknowledges that the colonial writers had their own take on people and events, different from his own professional understanding. Jones is by no means the first to accept that history is not one story, but he is one of very few scholars to adopt a system of writing that distinguishes quite sharply between documented voice, his gloss, and a powerful intuition about the form a particular intercultural zone has taken. He represents the latter in metaphor and image. Admirably, he has achieved the ostensibly impossible: seeming to have a concept of history as unified, he writes as if he knows it is not. His writing has a pleasing transparency, moving between ease and anxiety, rectitude and voluptuousness.

In the first chapter, Jones steps back from Keith Smith’s and Inga Clendinnen’s proposal that the 1790 spearing of Governor Phillip was a ritual punishment. Their approach, he writes, ‘too neatly fits a resistance model of history’. Some chapters later, however, he proposes that the 1869 spearing of John Bennett was a ritual punishment. The difference may reside in his attitude to the record. The reporters of 1869 were informed by almost a century of intercultural acquaintance, and in the detail of their reports can be read suggestions that a ritual killing was on the agenda, whereas the reporters of the 1790 incident were newcomers to whom the Aboriginal people were impenetrably strange. The reader will decide which stance is preferable: Jones’s, which goes no further than the incomprehension of the first settlers; or Smith’s and Clendinnen’s, which applies the wisdom accumulated over two centuries.

Jones’s method tests the capacity of written evidence. There is a spectacular clash between word and image in chapter 7. ‘The magic garb of Daisy Bates’ takes for gospel Bates’s claim in 1944 to have maintained the dress code (by implication, the proper standards) of Victorian times. Yet photographs reproduced by Jones (and other photographs I have seen) show that she did follow fashion, especially in her hats. In 1907 she wore a flamboyant affair currently in fashion. In 1922 her sailor hat and Edwardian garb were still more or less in date. At Ooldea in 1941 she wore the cloche hat and dustcoat so fashionable fifteen years earlier – not bad for the outback. On the streets of Adelaide in 1950, she wore a suit five inches longer, not as stylish but of similar cut, to that worn by the city woman walking behind her, and her hat is suggestively regal – not bad for a woman aged eighty-seven!

Oral memory gives rise to history. We are not told when the Lindsay family wrote down their benign memory that Cubadgee, a century ago, planned to set up a cattle station in his homeland. That invidious scuttlebutt also gives rise to history is to be seen in Jones’s breast-beating about the toas (way-markers) bought from a Lutheran missionary by the South Australian Museum in 1907. For various reasons, ostensibly to do with professional doubt, perhaps more because false accusation sticks, Jones has accepted George Aiston’s xenophobic claim made just before the outbreak of World War II that the toas were a hoax by the German missionaries at Kalilpaninna: ‘the German teachers there … are as cunning as rats. The great Toa hoax was got up by one of the teachers … he suggested the designs and supervised the making of those toas – a thing totally unknown to any of the tribesmen in this country.’ Aiston here actually contradicted what he had written fifteen years before: ‘Sometimes, if it is intended to convey a more lasting notice of the direction taken, a kirra or boomerang is stuck firmly into the ground and is sloped in the direction that the party has travelled. This is especially used if they have departed from the usual track.’ Thirty of the museum’s toas have the form of a boomerang.

It seems fairly clear to me that the background to Aiston’s slur was a garbled memory of the wholesale restoration of the toas by the South Australian Museum in the years before 1914. When the toas were first unpacked, many of them were found to be damaged. To aid the work or restoration, the curator borrowed the miniature drawings that the mission teacher Harry Hillier had made for Reuther (who wanted to publish a book about his entire collection, of which the toas comprised one third). Jones’s personal involvement in the story, through his work at the museum, may explain his conscientious, though curiously blind, endorsement of Aiston. The best aspect of this excellent book is the piquant imagery. Leitmotifs of red ochre and blood, flashing axes and chattering shields, circle and reflection, cross between the stories like so many signals. Memorable images do the main work of bringing forward the book’s underlying themes. Examples are the shield that ‘emerged from the darkness of its Point Malcolm cave only to enter the ethnographic cavern of the museum’; the private letter with the description of ‘an incident’ in a frontier camp ‘crossed through in heavy ink’. The circle in one context is the metaphor for a spearing; when ‘Bennett and his fellows were unaware that his compromising excursions had caused their rope circle to be regarded as a target, rather than a boundary’. In a later chapter, the circle is recalled and complicated by its power in Arrernte culture: ‘The rings of these circles contain and radiate sacred essence, the locus of “country” and home.’

The book moves from rust to ochre, so reversing the title (which initially had for me unfortunate overtones of Ruskin’s arch Sesame and Lilies [1865]). The book’s final photograph and closing paragraph, culminating in a tour of the red ochre trail to Parachilna, picture the ancestral blood staining the site of the mine. ‘Arriving, the profound calm of this scene seems to deny history, the fabric torn since those first encounters between ochre parties and Europeans, almost 150 years ago. The Aboriginal memories of Pukardu stretch back further than that … into the deep history of many generations.’ In the last chapters, the leitmotifs have moved from settler to indigenous memory, and from the accident of time into eternal symbolism. Jones’s nine stories have become one story.

Comments powered by CComment