- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Back in 1981, Richard White, in his seminal study Inventing Australia, dubbed the Australian concern with defining national identity ‘a national obsession’. It was a time when ‘the new nationalism’ associated with John Gorton and Gough Whitlam had reignited debate about anthems, flags and the paraphernalia of nationhood. The converse of this fixation has been the recurrent fear that the ‘cultural cringe’ has still not been laid to rest.

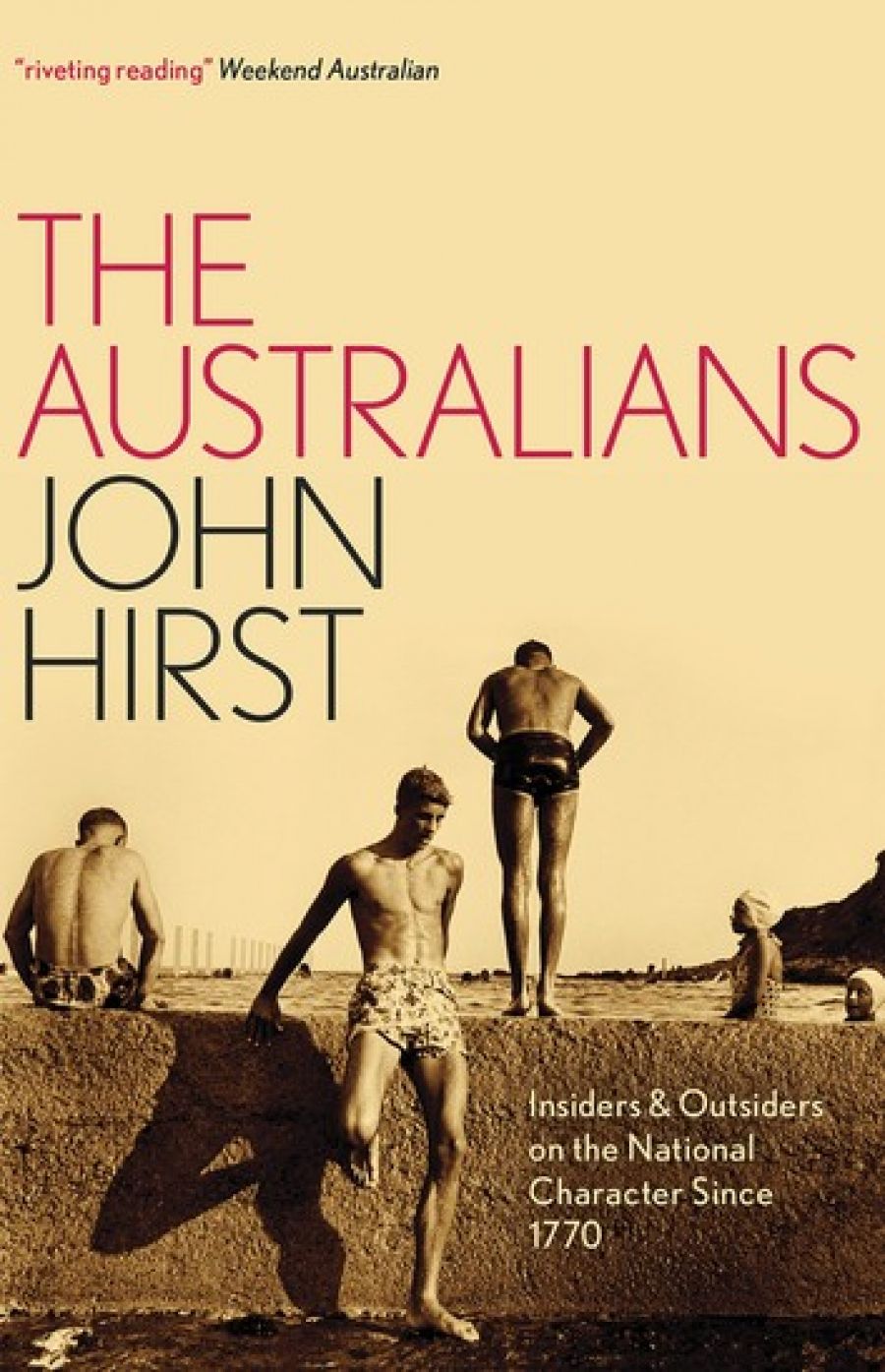

- Book 1 Title: The Australians

- Book 1 Subtitle: Insiders and outsiders on the national character since 1770

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $29.95 pb, 211 pp

White also argued that it wasn’t pertinent to ask whether ideas about national identity were true or false, but rather ‘what their function is, whose creation they are, and whose interests they serve’. John Hirst’s collection of documents, The Australians, comes to us courtesy of the National Australia Day Council, which acknowledges the generous support of ‘the Australian Government through the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet’. The collection also received support, presumably financial, from the ‘Quality Outcomes Programme’, administered by the Department of Education, Science and Training.

If this has the ring of official imprimatur – might the collection provide fodder for our very own citizenship test? – the choice of John Hirst as editor ensures that the result will not be a mere bland salute to nationalist clichés. Hirst himself played a significant role in breaking down the idea that there was such a single entity as ‘the typical Australian’, the product of one overarching national legend. And in this regard, the plural of the title The Australians is significant. Nevertheless, in the brief introduction, Hirst does nail his colours to the mast of ‘a national character’ that can give us ‘a sense of what unites us as Australians’.

Inevitably, some of the usual suspects turn up: Captain Cook on the ‘natives’, who are ‘far more happier than we Europeans’; Francis Adams on the Bushman, with whom ‘the final fate of the nation and race will lie’; Ned Kelly crossing verbal swords with Justice Redmond Barry when being sentenced to death; Charles Bean on the diggers and ‘their idea of Australian manhood’; Robin Boyd on the ‘material triumph’ and ‘aesthetic calamity’ of suburbia. Also, perhaps inevitably, the great majority of the voices heard are male, although feminist historians such as Miriam Dixon and the four authors of Creating a Nation (Patricia Grimshaw, Marilyn Lake, Ann McGrath and Marian Quartly) manage to get a word in to question the masculinist orthodoxy.

There are, however, some surprises. While diggers get a good run, winding up with the reputation they have won as peacekeepers, their older reputation as larrikin hellraisers is also acknowledged with C.J. Dennis’s now embarrassing attempt to justify the diggers’ trashing of Cairo’s red light district in ‘The Battle of Wazzir’, which the censor cut from The Moods of Ginger Mick (1916). In a chapter actually titled ‘Surprises’, Hirst quotes Turkish migrants praising Australians for their honesty and helpfulness, and quotes himself describing Australians as – far from anti-authoritarian, as the legend would have it – being a very obedient, law-abiding people. But should we be surprised on either account? The effect, surely, is to reinforce suspicion of any attempt to reduce ‘national character’ to some sort of all-purpose identikit.

If there is a recurrent theme in Hirst’s collection, it is the ambivalence that often characterises Australians’ relationship with their country. Hirst notes, with an almost masochistic satisfaction, the put-downs offered by foreign visitors, whether it be Beatrice Webb sniffing at the vulgarity of middle-class taste and manners, or D.H. Lawrence complaining of the mesmerising egalitarian tedium of colonial democracy. Not that Australians, local or expatriate, aren’t equally capable of putting the knife in. So we have Germaine Greer likening Australia to ‘a huge rest home where no unwelcome news is ever wafted onto the pages of the worst newspapers in the world’, and Bob Hawke dismissing Australia as ‘the arse-end of the earth’ (though his celebrated effusion after the America’s Cup victory of 1983, the other side of the coin, is not included). The choice of Henry Lawson’s story ‘His Country – After All’ to conclude the collection pays tribute to the fierce but grudging loyalty sometimes seen as characteristically Australian.

Mateship, of course, is always with us, but Hirst offsets it with that modern comforter, ‘the fair go’. And in this regard it is surprising that the preamble to the Constitution proposed in 1999 by John Howard (with a bit of help from Les Murray, who later dissociated himself from the project) doesn’t rate a mention. Howard wanted to have a bob each way, having us valuing ‘excellence as well as fairness, independence as dearly as mateship’. When it came to the referendum in 1999, we wouldn’t have a bar of it. It was a perfect example of the difficulty we have in reducing our feelings about Australia to a neat formula. And it suggests, too, that Richard White’s suspicion of the agendas of those making such pronouncements about national identity on our behalf is widely shared. In his much remarked appropriation of mateship, Howard has detached it from the collectivist ethos which was often assumed to be part of its inheritance. All that we are left with as a remnant of that tradition is ‘the fair go’. Like motherhood, who can be against it? Still, Howard makes it clear that you can have too much of a ‘fair go’: a veto will apply if it is in danger of producing ‘the excessive paternalism of some European societies’. For ‘European’ does one read ‘Scandinavian’?

In a foreword, Warren Pearson, national director of the Australia Day Council, concedes that there is no simple answer to the question, ‘Who are the Australians?’ In his brief introduction, Hirst sees the book as ‘designed to do good service to the nation by tracing both tradition and change in the Australian character. There are old voices and new. There is celebration and criticism.’ But in its embrace of criticism, the collection stops short of including those who, like White, question the whole project of national identity. For Hirst, ‘the civic values of democracy, the rule of law and toleration’ are not enough for a sense of nationhood. ‘Will anyone,’ he asks, ‘lay down their life for diversity?’ Toleration is not the most generous word in this context: to tolerate can sometimes mean no more than to put up with. But in this day and age, when the ugly face of fundamentalism accosts us in its different forms, it is not inconceivable that a diversity that values difference may be worth fighting for.

The Australians is clearly aimed at a general readership that, it is assumed, will be unfamiliar with most of the selected documents, and in these terms it is a good read. Nevertheless, it is a pity that Hirst’s introduction does not offer a fuller analysis of the debate about national identity. Curiously, the media release mentions ‘a set of dazzling introductory essays’ which appears to refer to the few contextualising comments that precede each chapter. Or did something get lost on the way to the printing press?

Comments powered by CComment