- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: White gloves and gladioli

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

When George Lambert returned to Sydney in 1921, he was celebrated as the most successful Australian painter of his time. With his cosmopolitan charm and forceful personality, he was in demand both socially and as a leader in contemporary art circles. For the previous two decades in London, he had exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy and the Chelsea Arts Club, rubbing shoulders with prominent British artists including William Orpen, Augustus John and William Nicholson, whose linear style and subject matter were not dissimilar to his own.

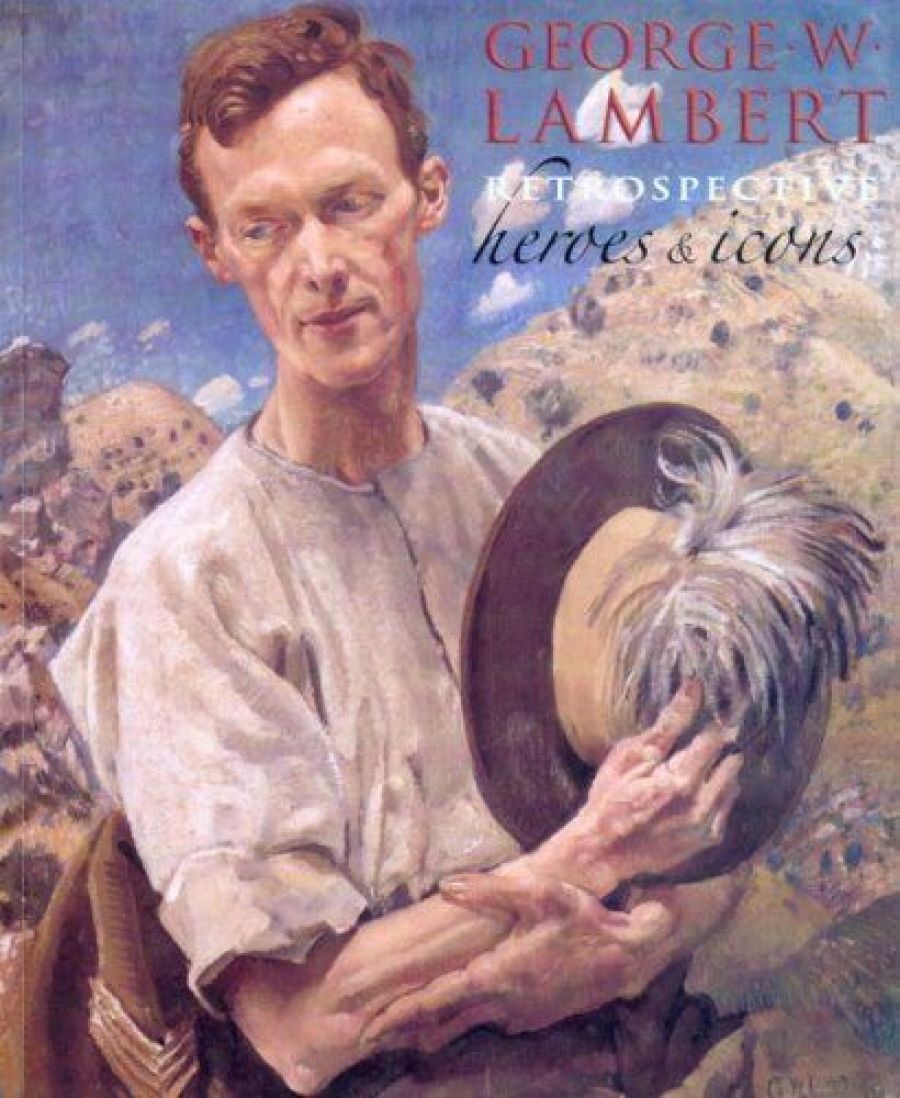

- Book 1 Title: George W. Lambert Retrospective

- Book 1 Subtitle: Heroes & icons

- Book 1 Biblio: NGA, $79 hb, 212 pp, 9780642541277

His works were purchased by the Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg and by the Tate Gallery in London. Lambert painted startling, bravura portraits with wit and panache. As a war artist in Palestine and Gallipoli, his small sketches and, later, his vast action canvases are among the best in the Australian War Memorial, in Canberra. Together with fellow expatriates Rupert Bunny, Emanuel Phillips Fox, John Longstaff and Hugh Ramsay, all of whom were Melbourne-trained, Lambert achieved recognition in Paris and London. As the first Australian painter to be made an associate of the prestigious Royal Academy in 1922, he followed in the steps of Melbourne-born sculptor Bertram Mackennal, who achieved this distinction in 1909.

Given Lambert’s prestige during his lifetime and the tributes and memorial exhibitions that followed his death in 1930, the delay in mounting this first major retrospective raises issues about the enduring quality of his work. Answers to the many questions surrounding his life and artistic status are admirably tackled in the comprehensive exhibition catalogue, George W. Lambert Retrospective: Heroes & Icons, by author and curator Anne Gray, Head of Australian Art at the National Gallery of Australia (NGA).

In her catalogue, Gray argues that Lambert’s oeuvre was largely obscured by the work of artists such as Russell Drysdale, Sidney Nolan, and Arthur Boyd, with their very different vision of the Australian people and their landscape. Ron Radford, director of the NGA, puts another case for the decline of his reputation, claiming that Lambert was a ‘celebrity artist’, whose sudden death at the age of fifty-six meant that nobody was around to promote him – except, of course, fellow artist Thea Proctor.

Lambert’s death coincided with the Depression and the advent of war, a time when his contrived paintings and esoteric allusions to European classicists did not appeal to the Australian public. Looking for a more robust and ‘relevant art’, they found his affectations and deliberate borrowings from the Mannerists, his flat, decorative linearity, his mannered hand gestures and elongated necks to be superficial, with little psychological insight. Today, however, these eclectic appropriations and arcane classical references have some relevance to postmodernism.

George Washington Lambert was born in St Petersburg in 1873 to an English mother and an American engineer who was working on the Russian railways and who died before Lambert’s birth. The family moved to Germany and England before migrating to an uncle’s property in Eurobla, New South Wales, in 1887. Here, from the age of thirteen, Lambert grew to love horses and Australian rural life. Recognised early for his drawing skills, he became an artist at the Bulletin. He also attended Julian Ashton’s Art School where he was a star pupil, winning the first Sydney Travelling Scholarship in 1901 with Across the black soil plains.

Lambert, recently married to the long-suffering Amy, set sail on the same ship as Hugh Ramsay, the loser of the Melbourne Travelling Scholarship, and a close friendship ensued. In Paris, they studied together and marvelled at the old masters in the Louvre, notably Velázquez. Lambert also admired Manet, Puvis de Chavannes, Botticelli, Giorgione, Titian, Parmigianino, Bronzino, and other Mannerists. For almost a decade, inspired by Ramsay, he painted large Edwardian baroque canvases, such as Lotty and the lady (1906) and many family studies depicting Amy with their sons, Constant and Maurice, as well as the much-discussed other woman in his life, Thea Proctor. Lambert became preoccupied by confrontational images of fully clothed, respectable gentlemen, often juxtaposed with seemingly unperturbed nudes, a tradition harking back to Giorgione, and repeated by Manet and others.

Gainsborough’s influence is seen in Lambert’s Miss Thea Proctor (1903), one of his more sensitive portrayals of a woman, and perhaps the first to introduce the mysterious image of an empty white glove. For almost thirty years, this symbol recurred like a leitmotif in pictures such as Pan is dead (1911), Miss Helen Beauclerk (1914), the astonishing portrait of a young Miss Collins camping it up in The white glove (1921) and The empty glass (1930).

Gray writes passionately about her subject and does not shrink from investigating the complex duality of Lambert’s private life: his exuberant theatricality on one side, and his melancholia on the other. Gray’s subjects – under subheadings such as ‘Friends, Colleagues, Artists and Students’, ‘Women and Children’, ‘Sexuality’ and ‘Recognition’ – are where she is most insightful. She also delves into Lambert’s preoccupation with his own image: whether dressed up as a Velázquez Philip IV lookalike, affecting the mannered gesture of a dandy in front of a bowl of gladioli, or the cheeky addition of his face in The convex mirror (c.1916).

In his theatrical self-portrait Chesham Street (1910), Lambert reveals himself bare to the groin, as in a marble Greek torso, an image that has something in common with the cover of Germaine Greer’s The Female Eunuch (1970). Is this tongue-in-cheek wit, or simply the reverie of a thespian manqué? When his controversial picture Important people (c.1914) was hung at the International Society’s 1914 exhibition, it received more critical attention than any of his previous works.

Despite Lambert’s claim to be Australian, he spent most of his productive life in England and his style remained quintessentially British. Since his return, his two major works depicting Australian rural life, Weighing the fleece (1921) and The squatter’s daughter (1923–24), may have acquired iconic status, but, as their titles suggest, they are artificial and say more about his connection to the pioneering Fawkner and Ryrie families than about any genuine relationship to his subjects. Lambert’s last decade in Australia was plagued by ill health and depression. Separated from his family in England, he was a lonely man, whose habits and compulsive commitment to work contributed to his early demise.

Since her definitive biography and catalogue raisonné, published in 1996, Gray has been the leading authority on Lambert. She knows her subject well: that is, as well as it is possible, given his complex nature. Lavishly illustrated, this catalogue shows the full range of Lambert’s work, from early bush subjects, large Edwardian portraits and figure groups, self-portraits, war paintings, his masterful drawings and later sculpture. Since it is seventy-seven years since his last major exhibition, this show is long overdue. Unfortunately, it is not travelling, which makes Gray’s catalogue the most comprehensive documentation of his works available outside Canberra. For quick reference, a short chronological outline would have been useful.

Comments powered by CComment