- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Deep purple

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

I was thinking a while back about some of the ways novels begin; not just the famous ones – ‘Happy families are alike’ etc, ‘Call me Ishmael’, ‘Unemployed at last’ – but also some contemporary examples. If I had read Michael Wilding’s National Treasure at that time, I would have conscripted it immediately: ‘Plant slipped down lower in his car seat as the man down the street was beaten up.’ Resounding first sentences often create the problem of where and how to proceed. Wilding manages very well: ‘He was quite a young man being beaten up, and the men beating him up were quite young too. So was Plant for that matter. Young. This was a young country. A young culture.’ These few lines signal quite a lot about how things are to unfold: the blandly matter-of-fact nature of the observation, so at odds with the nastiness of what is being observed; the non sequiturs breaking wildly beyond the apparent bounds of the narrative; and that isolated word ‘Young’, with its insistence, its tinge of impatience lest an obvious point be missed. My little burst of close critical reading is intended to foreshadow that among National Treasure’s various treasures is some wonderful writing.

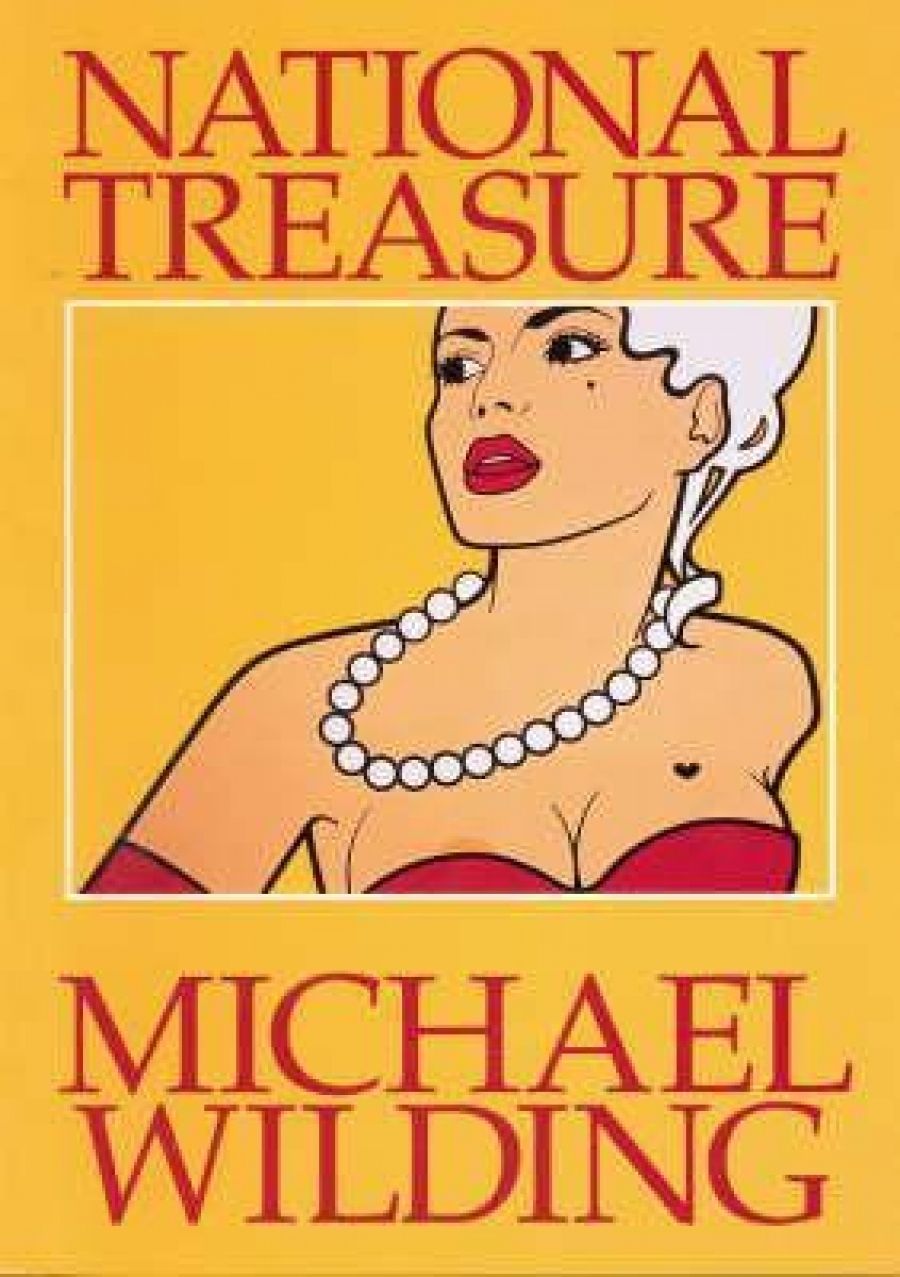

- Book 1 Title: National Treasure

- Book 1 Biblio: Central Queensland University Press, $25.95 pb, 259 pp, 192127400X

The beaten-up man’s name is Fullalove. Make what you like of that: all the way from ‘full of love’ (which Fullalove assuredly is not) to whatever evil resonance it picks up from being a reminder of Gordon Burn’s scarifying novel Fullalove (1995). Names, in any case, are important in this novel. By delivering the smashed-up Fullalove to the address he is given, Plant meets Scobie, a drug-raddled novelist – the ‘national treasure’, indeed – and his domineering partner, Claudia. The action is launched by means of several long, often zany conversations during which Wilding takes aim at, and unerringly hits, a wide range of mostly literary satirical targets. Writers employing research assistants, for example. ‘Everyone has them,’ Scobie tells Plant. ‘All the big names. You’re nobody without a research assistant.’ The implication that research assistance is potentially ideas assistance and eventually ghost writing for the imaginatively impoverished doesn’t stay buried for long.

These conversations, which advance the plot minimally, are transparently the vehicle for the satire and the jokes, which in turn are so good that you accept the device. Whether it is a series of epistles, a straight-faced, modest proposal or a fantasised wartime island off the Italian coast, satire needs its devices. Wilding’s, in National Treasure, is conversation, in which his control of rhythm, tone, interruption, cross purposes, insult and riposte is mostly pitch perfect. Early on, Plant learns that Scobie’s current novel, which is about the illegal trade in organs robbed from mortuary bodies, will be called Body Parts. Research assistant Fullalove, Scobie explains, had been ‘Digging up the data … The newspaper story gave me the skeleton. Fullalove was helping flesh it out.’ Neither Scobie nor Wilding can help himself. Almost every chance for a pun, a wisecrack, a joke is taken, which inevitably means that there are some he should have passed on as too easy – Claudia’s Volvo being called a Vulva, for example. But in general the wit is exhilarating, confident and pointed.

The Australia Council, literary grants, Australian Studies, globe-trotting literature professors, postmodernism, literary fraud, plagiarism, ‘discovered’ Aboriginality, the 1960s and much else, all get due and often corrosive attention, with every now and then a brilliant, encompassing précis of some big picture or other. Like Claudia’s Sixties:

Sarongs. Bare breasts. Indian prints. Here at Ginsberg’s feet. There laying hands on Burrough’s rifle. Here exchanging smiles with Timothy Leary. There with the Marchioness de Fauxmonnayeur. Here with Lady Brewinglord. Love-ins. Smoke-ins. Country inns. Pheasant shooting. Rock concerts. Parties. Parties. Rock concerts. Moments of protest. More parties. More rock concerts. More Lords and Ladies. Long purples. Deep purple. Purple lined passions of sweet sin.

But Wilding’s target above all is publishers and publishing. Plant, gazing on the harbour, dreams of owning a boat, a ‘powerboat … A publisher’s boat rather than a writer’s. Serious wealth’; and Scobie snorts at the publishing world, packed with twenty-four-year-old women, all named Fiona. Scobie’s publisher, Bentley, is a predatory, plausible, low-life fraud.

A post-it note at page 55 tells me where I began to suspect the answer to the growing enigma in this book – not because I am so smart but because there are carefully planted, oblique clues if you can look past the fireworks.

National Treasure is the thoroughly enjoyable, sometimes hilarious story of eccentric, if not ‘mad’, people who live through outlandish events and imbroglios (a Wodehousian word, appropriately enough, because Plant, at one point sounds and acts like a butler and parrots Jeeves’s very words). But it is not lightweight: it is tough, well-calculated, smoothly witty satire.

Comments powered by CComment