- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: 'Forget the housework'

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

If you didn’t read Meg Stewart’s gentle, courteous Autobiography of My Mother when it was first published in 1985, no matter. This second edition was precipitated by the research of others. ‘What My Mother Didn’t Tell Me’, the title of the additional chapter, is that Margaret Coen, Meg’s mother, had a long affair with Norman Lindsay in the 1930s. Lindsay was married, in his fifties; Margaret in her early twenties. The first edition is hardly altered, and only the new chapter challenges Coen’s reticence, causing us to think hard about oral history.

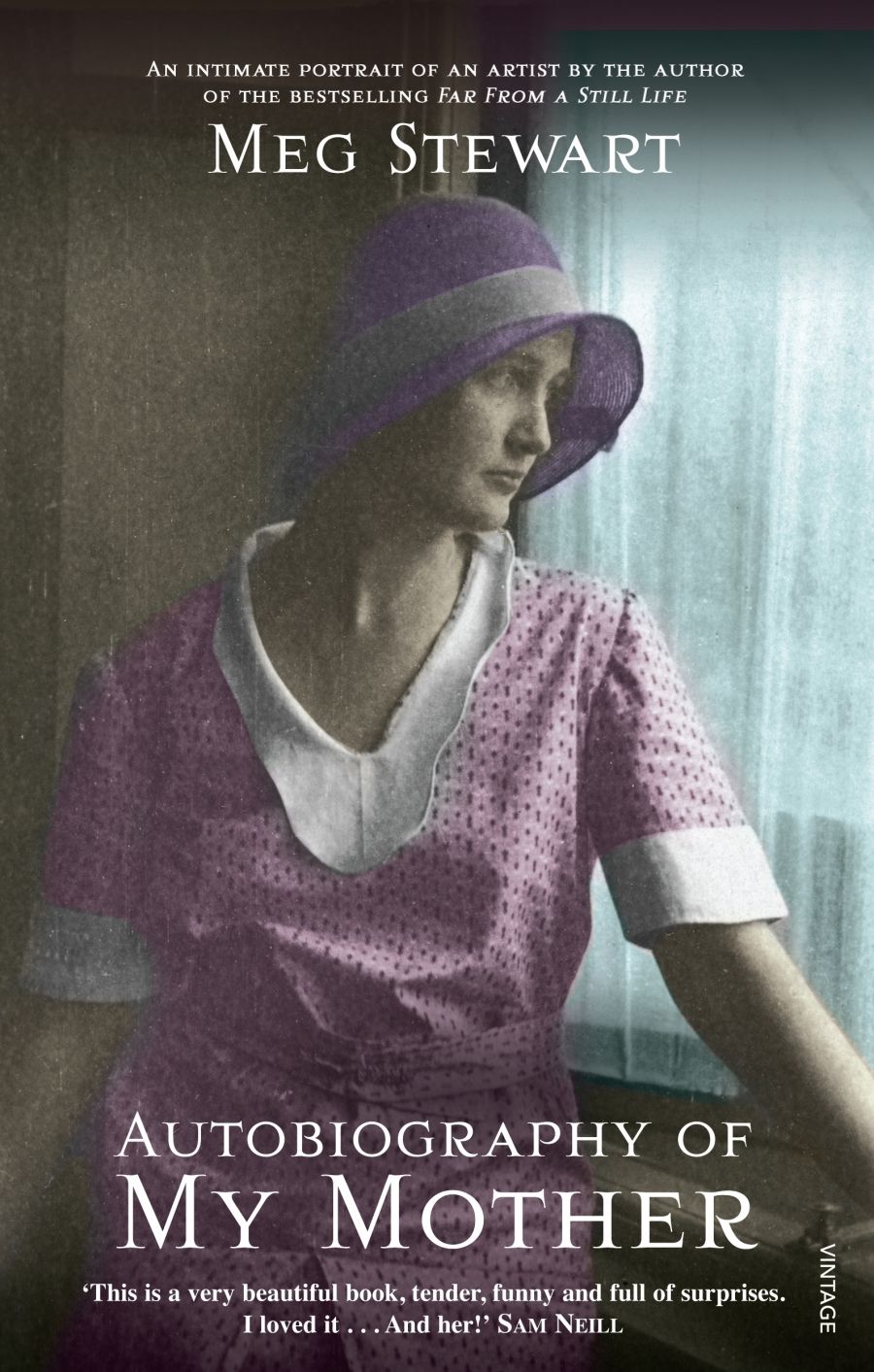

- Book 1 Title: Autobiography of My Mother

- Book 1 Subtitle: 2nd edition

- Book 1 Biblio: Vintage, $27.95 pb, 356 pp, 9781741668230

Coen, who would in 1945 marry the ‘dark, intense’ poet Douglas Stewart, was a talented watercolourist, neither more nor less. The lessons of her life and memories, for the reader, is that she was an artist. This is not simply how she described herself but what her life was about. The book shines with her calling, her dedication to drawing and painting. Late in life, she tells her daughter: ‘My advice to women who want to work is to forget the housework. Do your painting or writing or whatever first. It’s not a bad idea to make the bed ... If you do the housework first, you’ll be nagged by the feeling that you would rather be doing your own work ... Swapping gossip over the back fence or discussing husbands over cups of tea are definitely out. You must get on with your work. That’s how I survived nearly forty years of marriage and working at home.’

Yet when Coen, who had the stamina to make her living as a commercial artist in the 1920s and 1930s, when jobs were scarce, remembers the studios she shared with fellow artists, including Lindsay, in the bohemian heart of Sydney (all glitz and commerce now), there are enough stories about cleaning and caring and feeding stray cats to paint a picture of a thoroughly well-brought-up young girl who could do both. She took great joy in her friendships; if ever you are to be remembered by someone, then let that someone be like Margaret Coen.

Hazel Rowley, in her recent ABR/La Trobe University Annual Lecture (published in this issue), suggested three rules for a biographer: use the sublime, not the superfluous details; write a lively narrative; and always be in sympathy with the subject. It is interesting to apply these rules to what is at heart an oral history.

The narrative we must thank Meg Stewart for. Although she gives Coen the entire space to tell her story (the book’s uncommon and great courtesy), it is no mean feat to turn what were presumably taped sessions into a cogent, charming, even tender whole. Someone who knew Margaret well and who also knew many of the people in the book, said to this reader, ‘Meg has got Margaret’s voice down perfectly’. This is not the obvious outcome of an oral history. Sympathy is not the obvious trait it might superficially seem to be in a mother–daughter relationship either, but Stewart’s love for her mother, literally outside the pages, is in the air.

Does the revelation of Coen’s love affair with Norman Lindsay count as a ‘sublime detail’? None of the evidence is so bold as to include mention of the intimate act. Central chapters in Coen’s narrative combine to give a marvellous, lively picture of how poor artists and writers lived and loved and caroused in a now unrecognisable Sydney, but the casual, euphemistic phrases of a later era (‘sleeping with’, ‘in bed with’, etc.) are missing. Coen, educated by nuns at Kincoppel, was a nice girl who loved to draw and paint flowers. The mystery of what she chose to keep to herself, now revealed, remains, for this reader, a private affair. But not, one supposes, for Lindsay enthusiasts and scholars.

Three-quarters of the way into the book, we are only up to Coen’s twenty-fifth year; the next fifty years are snug in a mere eighty pages. Is this what one gets when old age paints the distant past most vividly, or is it evidence of a different reticence? Was Stewart going to ask to hear more, but later?

Reading the book again, you question things you did not notice first time around. This is never a matter of distrust. Coen was obviously a remarkable woman, and the marvellous energy she gave to her work, to friendship and fun, is evident. And one of the little wonders of what Coen chose to remember is that Sydney becomes a character, just as a different part of it did in Ruth Park’s novel Poor Man’s Orange (1949). Whatever adjustment one has to make in the light of what Margaret didn’t tell Meg, it is the story of a young girl’s love of painting and her education as an artist in that big city during a different time that is still the centre of the story.

Comments powered by CComment