- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Journals

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Eros and politics

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Roland Barthes called language our second skin: ‘I rub my language against the other. It is as if I had words instead of fingers, or fingers at the tip of my words. My language trembles with desire.’ Which should make the latest Meanjin, ‘On love, sex and desire’, a veritable Kama Sutra of literary massage. Yet it opens, perversely enough, with a denunciation of the erotic. John Armstrong’s honest, elegant and sharply self-critical essay recounts an early sexual experience during a brief trip to Paris. Giving his father the slip one morning, the teenager snuck off and spent his money on a prostitute. Afterwards he wandered the streets, full of loathing: ‘I was wicked, stupid, naïve, vile, corrupt, irresponsible, thick, wasteful, out of control, nasty, brutish.’

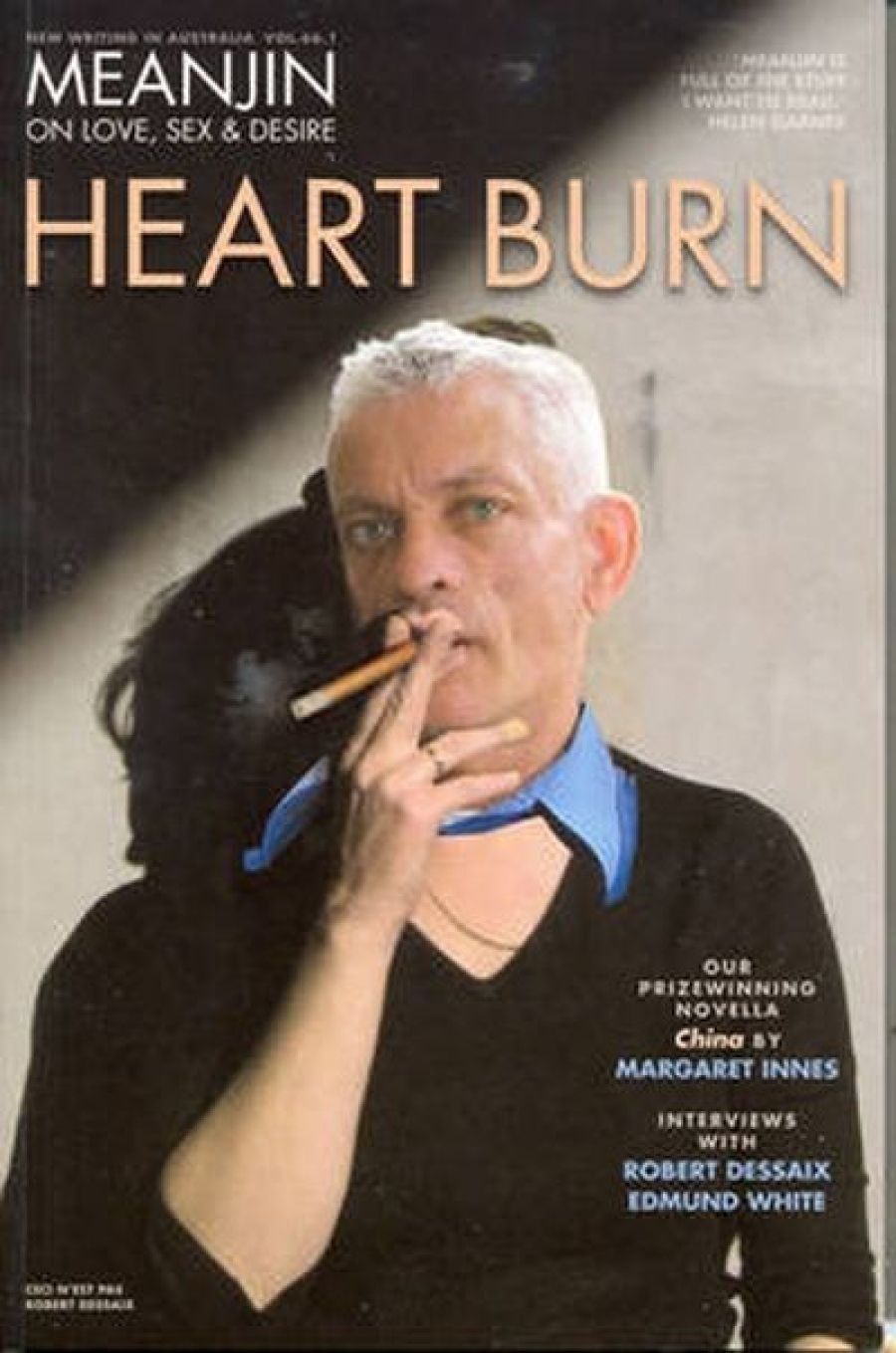

- Book 1 Title: Meanjin Vol. 66, No. 1

- Book 1 Subtitle: On love, sex and desire

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne University Publishing, $22.95 pb, 234 pp,

- Book 2 Title: Overland 186

- Book 2 Subtitle: The frightened country

- Book 2 Biblio: $12.50 pb, 96 pp

Armstrong sees in this scenario a re-enactment of that ‘endless struggle between sex and civilisation’. He draws the conclusion that there is no such thing as ‘eros without tears’. Sex without higher ambition – Plato’s noble desire, which seeks to enhance and increase beauty – is mean. ‘Eros manifests itself in base people. What we call erotics – the “science” of sexual arousal – turns out to be residue, what’s left over when things go wrong …’

He could be right. But had Armstrong overcome the temptation to climb to that ‘hot little attic’ in the Pigalle, and instead gone to the Louvre or spent his francs on improving books, would he have been qualified to make the judgment? He writes that the encounter left him feeling locked inside himself: cut off from the pure, disinterested beauty of art, books, music. I would have thought he had opened himself up to a clearer sense of their virtues.

James Ley, reviewing two recent novels by Rodney Hall and Kate Legge, is less interested in eros than in romantic love. He ponders whether Freud is right – that love is an overvaluation, a projection of our own feelings toward the love object – or Auden, who considered that love creates its own reality, that we truly know someone only by loving them. Although Ley admits to being an incorrigible romantic, he concludes that these positions are locked in dialectical embrace:

Love points to how things ought to be. It faces the future rather than the past and, in this sense, it is a form of idealism: not simply utopian but, as literature has so often depicted it, rebellious … Love thus contains the seeds of tragedy, but it is also a form of hope.

There are also several fine capsule biographies of literary relationships. Anne-Marie Priest half admires the ‘passionate, fragile and contradictory’ figure of D.H. Lawrence, examining his sad early liaison with Jessie Chambers before moving on to his tumultuous marriage to Frieda von Richthofen. According to Brenda Maddox, the pair got it on within twenty minutes of first meeting.

Meanwhile, Michael Ackland looks at two literary couples. He writes of Henry Handel Richardson’s embrace of spiritualism, a touching attempt to maintain contact with her beloved partner of four decades, John George Robertson, in the Great Hereafter (he continued to dispense solid financial advice to her from beyond the grave, apparently) before moving on to Christina Stead’s enduring love for the redoubtable polymath Bill Blake. Ackland writes that theirs was ‘one of the great literary partnerships of twentieth-century Australian letters’. I’d say: of twentieth-century letters, period.

The deeply uneven quality of the poems in this number reminded me of Auden’s aversion (curious, given his own first-rate efforts) to love poetry. However, Lucy Holt and Craig Billingham’s contributions – along with the first of Benjamin Cornford’s two poems – stand out. Whether oblique or angry or just plain strange in approach, their success lies in avoiding the usual weary tropes.

Other pieces to turn to first include Peter Rose’s meditation on poetry and obsession, ‘The Yellow of Unlove’, Lachlan Strahan’s anatomy of male friendship – examined through the lifelong bond between his archivist father, Frank Strahan, and the Renaissance scholar Ian Robertson – and Beverley Farmer’s marvellously brisk and biting essay, ‘Eros in Dreamland’. One to skip is John Heard’s queasy Q&A with Edmund White:

J.H: Would you ever make a porno?

E.W. Only if you did it with me.

From pornography, then, to real obscenity. The new Overland (‘The Frightened Country’) looks at the Howard government and the politics of fear it has so successfully and destructively bruited since 9/11. In his introductory essay, outgoing editor Nathan Hollier quotes Carmen Lawrence on how the current mob have

used fear to legitimise questionable actions, to attack its detractors, and to foster a climate of timidity … Its apologists have made an art form of vilifying critics, apparently hoping to muzzle them with abuse. Fear has proved a potent device for managing dissent and silencing those who object to government policy or who seek a greater share of power and resources. A drift towards authoritarianism has likewise been evident in many areas of government policy.

Overland has always been a journal fuelled by righteous indignation, and to be fair the quoted passage indicates how Howard has provided an almost inexhaustible supply of the stuff. But must everything it touch turn to politics?

Katherine Wilson’s ‘Thought-Crime and Punishment’ is a clear and powerful exposé of one result of this country’s juridically repugnant anti-terrorism legislation. I had not been aware of the situation of the Barwon 13 and was glad to learn of it – undoubtedly it is a travesty of justice. But surely we have only so much anger to husband. I would have saved mine for the forty-two Iraqis murdered by a car-bomb overnight, rather than railing against the ‘noisy, over-air-conditioned vans’ used to ferry the Barwon prisoners to court.

Likewise, in ‘The International of Excreta’, which examines the fraught relationship between ‘national’ literatures and globalisation, Andrew McCann makes a worthy case for giving the finger to Verlagsgruppe Georg von Holtzbrinck et al. And yet his prose is packed with over-egged with quotations from Adorno, Benjamin, Fredrick Jameson, Alexander Kluge, Negri and Hardt – a mandarin of theorists (to coin a collective noun). I persisted, but lost my temper at the point where McCann argues that aesthetic autonomy from economic forces is best achieved by texts which ‘shatter coherence’ (in this case, Juan Goytisolo’s State of Siege [1995]). This, to borrow McCann’s own term, is excreta. One of the central features of the transition from industrial to post-industrial societies, aside from evil publishing conglomerates appropriating marginal literatures, is an exponential rise in theoretical knowledge. Critical theory is thought exiled to the ghetto of the academy, where it can discuss the potentially liberating effects of shattered coherence without troubling the powers that be. In an age of corrupt political discourse, coherence is the most radical and least politically beholden response I can think of.

So it was with relief that I turned to poetry editor John Leonard, whose crisp, schoolmasterish guide to not writing terrible verse was refreshingly practical. Also worthy of note is Keith McKenry’s account of how the young Rev. Percy Jones became, almost by accident, the man who saved such folk songs as ‘Click Go the Shears’ and ‘Botany Bay’ from oblivion, as well as Dennis McIntosh, whose novel extract, ‘Waratah Station’, has a rough-hewn intensity that surprised and engaged me. Anthony Ashbolt’s education essay also turns to theory, but does so with verve and a pocket full of (damning) facts about the public/private school funding divide.

Still, overall, the feel is that of a magazine which has spent too long on the back foot. In his valedictory editorial, Nathan Hollier writes that ‘while I greatly enjoyed editing Overland, I also found it stressful and felt myself to be isolated within the Australian literary and intellectual public sphere …’ Indeed. Which made me think of Cyril Connolly, writing of Orwell’s lonely journalistic efforts during World War II: ‘But O the boredom of argument without action, politics without power.’

Comments powered by CComment