- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Travel

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Intrepid or intrusive?

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Jane Austen’s latest biographer, Jon Spence, observes that by deciding to support herself by writing rather than live on a husband’s income, Austen was spared the likelihood of annual pregnancies, exhaustion, infection and early death, fates that confronted many married women of her day. Another means of avoidance was travel abroad. That was not the only motive, of course, of the many European women who, from the early eighteenth century, attracted admiration, censure and curiosity by combining writing and travel. Nor did it always work.

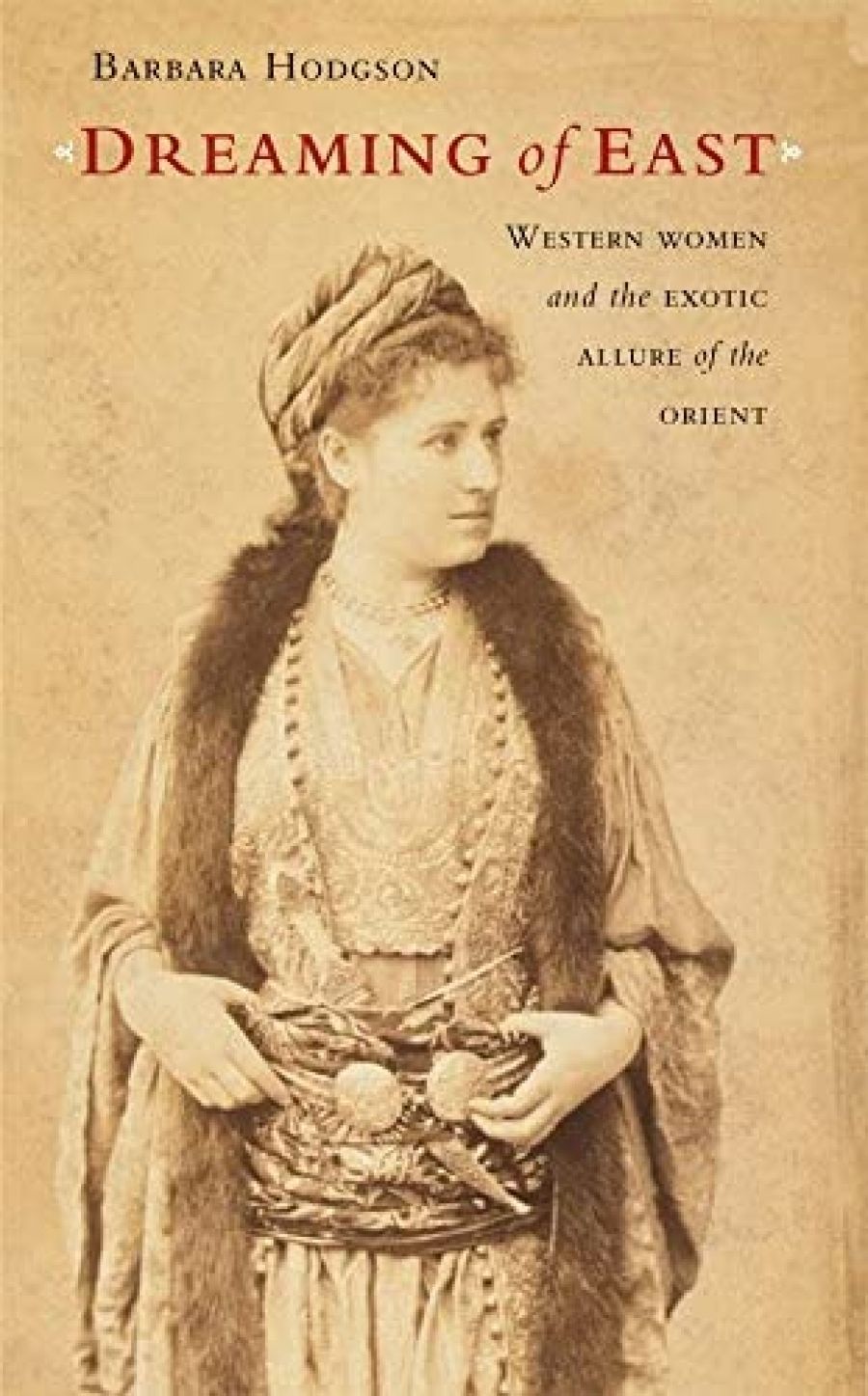

- Book 1 Title: Dreaming of East

- Book 1 Subtitle: Western women and the exotic allure of the Orient

- Book 1 Biblio: Hardie Grant Books, $29.95 pb, 184 pp

- Book 2 Title: Women of the Gobi

- Book 2 Subtitle: Journeys on the Silk Road

- Book 2 Biblio: Pluto Press Australia, $29.95 pb, 262 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

Some of the women travellers to the ‘Orient’ fell in love with their dragoman guides, many had affairs and a few had babies. Others took along women partners who remained discreetly anonymous. Several sported exotic local outfits, while others, notably Freya Stark, dressed as Middle Eastern men. The formidable Lady Hester Stanhope headed a touring party that included male advisers and a lady’s maid. Some, such as Isabel Burton and Anne Blunt, travelled with their husbands; others went with brothers or daughters.

The women they met in the Middle East, Barbara Hodgson records in Dreaming of East, reciprocated the travellers’ interest and offered hospitality. This gave the European women an edge over male writers in being able to report from inside the harem, ‘behind the veil’. But that privileged access didn’t save them from furious assertions by men with a particular patch to protect, that the women were incompetent and should stay at home where they belonged.

For centuries, gentlemen had headed into the unknown, typically taking along Herodotus and Thucydides, or some equally battered living companion. They would then write about their experiences with a combination of erudition, nuttiness, wit and eloquence. The best travel writing is still done by insouciant Englishmen, who always seem able to do it without exaggerating or bragging. If an upper-class Englishman had been searching for the Muslim tomb in western China, Kate James reflects enviously in Women of the Gobi, he would first have visited specialty bookshops in London,

where he was on a first-name basis with the charmingly eccentric owners.

In Jiayuguan, he would have hired a four-wheel drive, a driver, and a translator. They would have travelled out to the Muslim tomb village together, discovered the tomb, and spoken to the caretaker [who] would have told the translator fascinating stories and taken everyone home for lunch.

Whether Barbara Hodgson’s women travellers went as scholars, artists, tourists, adventurers or ‘free women’, the experience changed their lives. Some never readjusted to European society afterwards. In spite of the prevailing belief that ‘Oriental’ males were so oppressive that European women would be happy to escape their clutches, many recorded the courtesy and respect shown them by men. Moreover, Hodgson points out, throughout the period that she covers, from 1717 to 1930, women’s rights were circumscribed in Europe, too. Indeed, it was in the Middle East that many of them could escape such restrictions and manage their own lives for the first time.

Hodgson, who lives in Canada, has written several other books about women’s travel. She is also a book designer, and Dreaming of East includes a sumptuous collection of historic images, including paintings and photographs made by the women themselves. The catalogue record for the illustrations can be seen on the website of the National Library of Australia.

Kate James’s parents were missionaries in India. James, having abandoned their faith, has been a journalist and an editor for Lonely Planet. In Women of the Gobi, her first book, she asks the same questions about women travellers as Hodgson: why did they go? why is it interesting? Her few pictures don’t match Hodgson’s, and she barely mentions comparable Englishwomen Gertrude Bell or Isabella Bird; nor does she say anything of such Australians in China as Hedda Morrison or Peggy Warner. James’s focus is tighter: instead of surveying dozens of women over two hundred years as Hodgson does, she goes back in history to 1893, and physically retraces the journeys made by three English missionaries to the western edge of China.

Eva and Francesca French and Mildred Cable were only in their twenties when they went to China in the 1890s to save souls. The Trio, as James calls them, spoke Mandarin, ran a successful girls’ school for twenty years, and adopted a deaf-mute Mongolian girl, whom they called Topsy. Later they travelled repeatedly across the Gobi desert in a mule cart – teaching the Gospel, even giving Communion – and wrote nineteen books. Celibate and abstemious, they often lacked food and shelter, and were threatened and robbed. When they were arrested during the missionary-hating Boxer uprising, they sat silently like three Buddhas rather than argue, and managed to escape. James recounts their tribulations and near-miss experiences, but stops just short of implying heavenly intervention. When Mildred had a frostbitten nose, she was lucky, James writes, not to end up looking like Michael Jackson. The Trio returned to England in 1936, where one by one they died. Topsy died in 1998.

With a publisher’s advance, James did preliminary research on the Trio in England and Germany, and took Mandarin lessons, before setting out across China to the western desert, mainly by train and bus. The little camel figure that divides sections in the book is purely decorative: neither she nor the Trio travelled by camel. With the aid of modern technology – an MP3 player, a Game Boy, a laptop and a mobile on which to phone her mother and boyfriend in Melbourne – James had a quicker and less dangerous journey than the Trio, with Internet cafés all the way. Even so, she was pretty intrepid herself, fending off amorous advances, surviving illness and finding her way without much language.

James was joined at the edge of Han China by her similarly apostate brother, who was keen to eat donkey. But Jack shared her interest in the Christian Trio, her liking for cold beer and her taste in pop music. American songs blasted at them in Chinese buses, trains and restaurants; they even heard Kylie Minogue in Uyghur. James drily evaluates hotels, dumplings, noodles, kebabs and toilets, à la Lonely Planet. Each chapter is headed with a witty passage from Monkey, the modern English translation of the Chinese classic Journey to the West. James entertainingly interweaves local history into her search for places written about by the Trio, culminating appropriately in Urumqi with Heaven Lake, their favourite.

So what, in the end, were all these women’s exploits worth? Some of the Middle Eastern ones remain famous, or notorious, but clearly they did not dispel notions in the West about the Orient. The Trio made few converts, and are little remembered in China, where Christians are still a confined minority. James decides she admires not so much what they did but the way they did it, laughing at themselves, but holding to their beliefs, and respecting those of others. They all deserve to have been rescued from near oblivion.

Comments powered by CComment