- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Conjuring exiles

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Here are two novels of exile, one contemporary, the other about coming to Australia in the nineteenth century. In Carol Lefevre’s Nights in the Asylum, Miri, a middle-aged actress, escapes from Sydney and her tottering marriage, and drives back to the mining town of her childhood. On the way, she picks up an escaped Afghan refugee, Aziz, and drops him off in town, where he immediately falls foul of the inhabitants and ends up on the doorstep of Miri’s family home, uninhabited while her aunt is in hospital. The house becomes asylum for more than one outcast: Zett, the abused wife of the local cop, has already found herself there, baby in tow.

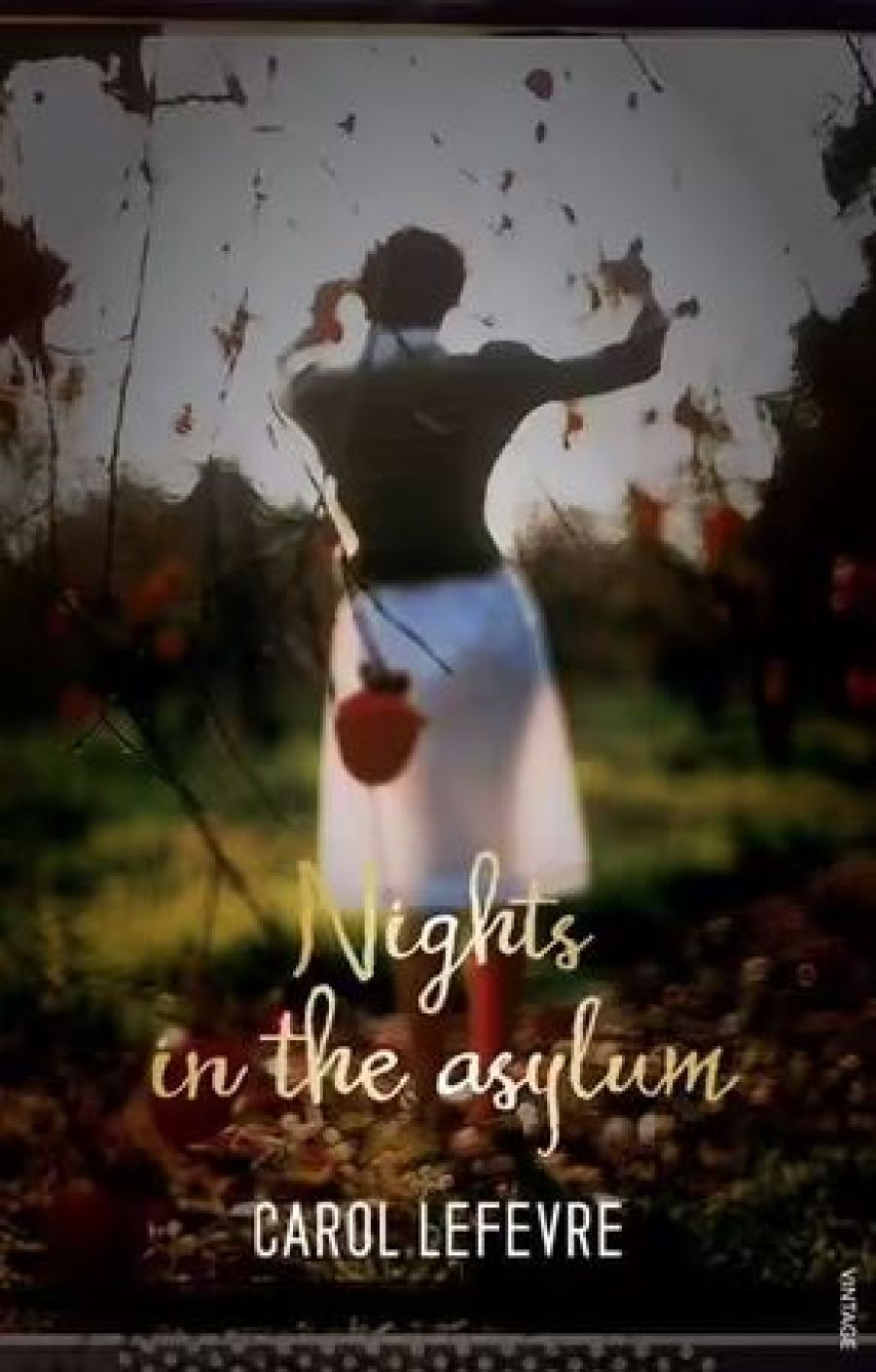

- Book 1 Title: Nights in the Asylum

- Book 1 Biblio: Vintage, $32.95 pb, 316 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: www.booktopia.com.au/nights-in-the-asylum-carol-lefevre/book/9781741665338.html

Lefevre offers us nothing so lurid, although a scene at the end, involving Zett, Jude, a gun, and a polaroid camera, is fairly rich. The set-up may have more than a whiff of sentimentality to it, though page by page her treatment is self-possessed enough not to outrage one’s sensibilities.

For all that, the most powerful sequences in the book are not about small-town prejudice but are the flashbacks about Miri’s relationship with her university-age daughter as she withdraws and then breaks down completely, leading to the funeral that opens the book.

You also wonder if our recent interest in asylum seekers is encouraging a new progressive form of Orientalism, with soft-eyed, dark-skinned men the new odalisques, the new embodiments of an exotic sexuality. Aziz is contrasted both with Jude’s blond beastliness and with Miri’s tomcatting film-director husband. In the Hannie Rayson play Two Brothers (2005) and the David Williamson Influence (2005), Middle Eastern immigrants were presented as saintly sufferers, as latter-day Smikes or Little Dorrits; Lefevre is more subtle, but her vision of Aziz is severely circumscribed by Occidental romanticism. Passages like this have a rather Condé Nast flavour:

From the beginning, Aziz had favoured the rich red Turkmen carpets, but he appreciated the simplicity and vigour of lesser rugs. There was poetry in carpets, especially the tribal designs, whose colours and patterns vibrated in harmony with some inner gland that both calmed and stimulated his senses. The work was hard, but Aziz never minded.

and later:

Her beauty was of the same calibre as a rare antique carpet his father had once owned, its silken surface busy with hundreds of flower motifs, honeybees, butterflies and tiny hummingbirds. His father had prized this carpet for the beauty of its dyes infused from walnut husks, pomegranates, autumn apple leaves, chamomile, saffron, cinnabar and indigo, and for its holy image of a garden, an intricate blue and gold paradise, behesht.

This kind of deluxe culture-fetishism is a bit better than thinking that they’re all terrorists or wife-beaters, but really, it won’t do.

Eugene's Falls by Amanda Johnson

Eugene's Falls by Amanda Johnson

Thompson Walker, $34.95 pb, 360 pp

A grander exile is the subject of Amanda Johnson’s Eugene’s Falls, also a début, and the book is formally and intellectually much more ambitious. Johnson’s subject is the life of Eugene von Guérard, from his childhood in the Vienna of Franz I through his Italian years and thence to the Victorian goldfields and his attempts to interest the new colony in heroic landscape painting. It is a folly stuffed with talent well and badly deployed, any real structure buried beneath its author’s fascination with what she can bring to bear on the subject: the history of Romanticism, the early history of the steam train, Aboriginal languages. The method is essayistic rather than dramatic: Johnson proceeds by absorption, and while this makes the book locally powerful, it also makes it hard to assimilate at length. The climax of the book is not so much an action as it is a tableau – von Guérard and a group of English and Aborigines he encounters in the forest – and it is both over-elaborated and inconsequential.

It also takes a while for the style to calm down; the book only comes into its own when von Guérard reaches Naples. Johnson spends too much time at the beginning on the postmodern throat-clearing, which tells us that what we are about to read is a story, a construct, a product of the here and now, rather than masquerading as pure emanation of the subject matter. This she never lets us forget, introducing all kinds of anachronisms into what might carelessly be read as a free, indirect style: we may think we are seeing things through von Guérard’s eyes, but when Johnson compares the line of the Alps viewed in the late 1820s to a cardiogram, we know the author is hovering not far away (Eugene and his father are traipsing across to Italy). It is a perfectly respectable strategy, but sometimes this makes the writing go completely flat: there are passages where the style embodies no one’s perception at all and starts to sound like the more flowery forms of scholarly nonfiction:

The new push [photography] was all about exposing and metering; shuttering and emulsifying. A vastly different thing to fitting together some poor mosaic landscape scraps. The whole continent had been speedily shuttered and recaptured as colourless silver spirit … On the other hand, this rather tense business of artisticology meant that painters like Eugene had been forced to theatricalise themselves in matters of dress and behaviour, styling themselves into silhouettes of genius or numb-headed savant; with nothing else in between.

It is a manner that suggests neither prosy, fact-filled naturalism nor the gleaming ruminations of Robert Musil or Milan Kundera, but the sound of someone trying and failing to turn their research into the material of art, and echoing the academic tone of their sources into the bargain. The book spends a lot of its time sounding more an experiment in postmodern biography (remember ficto-criticism?) than it does like a novel.

Comments powered by CComment