- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The Castles claque

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The roll-call of Australian female singers of the past resounds like a comforting resurrection of anachronisms: Ada Crosley, Florence Austral, Gertrude Johnson and the epitome of stardom, Melba. The name Amy Castles represents another thing, as Jeff Brownrigg’s recent addition to the cultural history of early Australian songbirds attests. Born into a Catholic and unmusical background in Bendigo in 1880, she was destined to suffer a condition not unknown to musical novitiates: vastly more hype than talent or accomplishment.

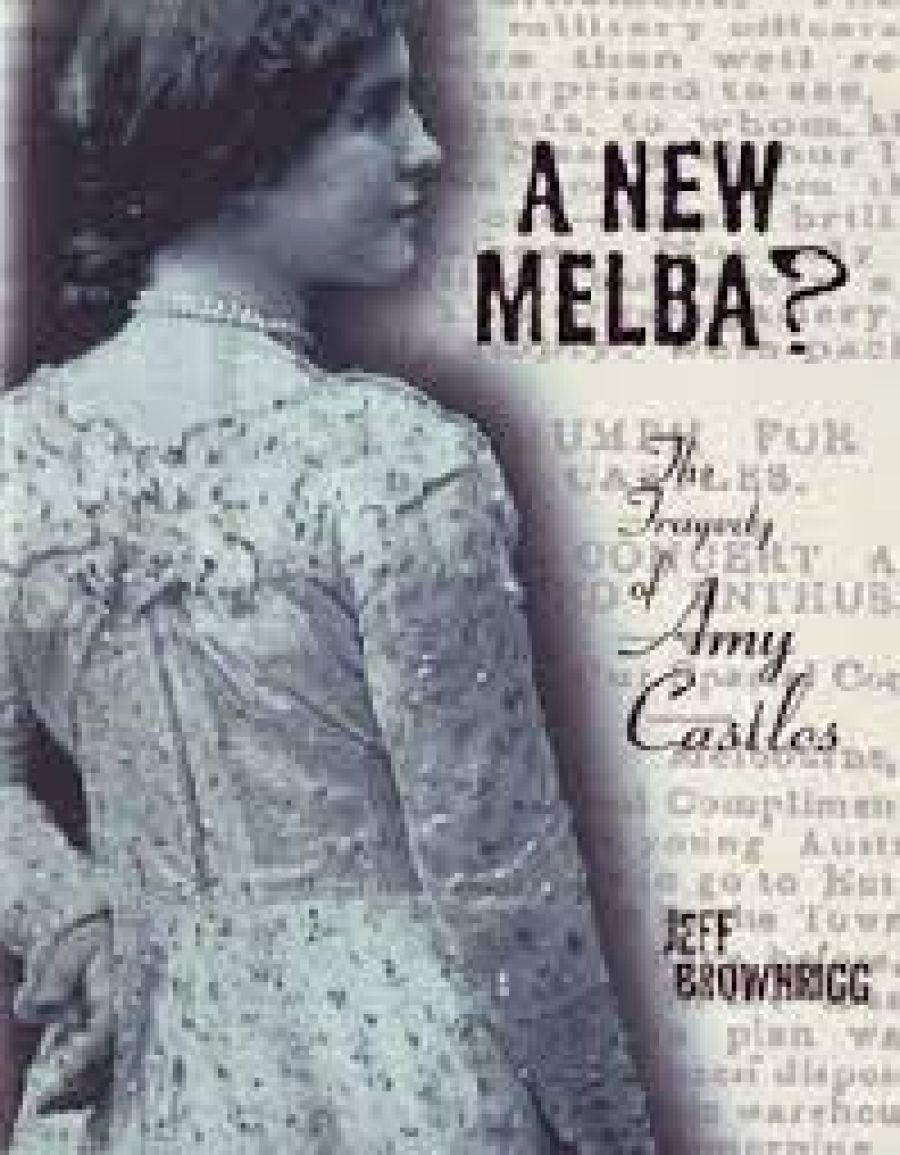

- Book 1 Title: A New Melba?

- Book 1 Subtitle: The tragedy of Amy Castles

- Book 1 Biblio: Crossing Press, $49.95 pb, 300 pp, 0957829191

Brownrigg’s meticulously researched volume does not spare us the extent and sheer musical ludicrousness of this hype. Intensely sectarian in origin, ‘the Castles camp’ was to become the tool of a Catholic backlash against the secular, gaudy and Protestant Melba, all intermingled with a wave of national guilt that Australia had failed to discover she whom Europe effectively enshrined as the greatest living soprano of the era.

Castles’ attributes were clearly limited. Gifted with attractive tone production, she never seems to have conquered scrupulous intonation. Her languages were poor, her professional training – some of it with Melba’s great teacher, Marchesi – brief and sketchy. The detailed account Brownrigg supplies of her professional appearances indicates a performer unsuited to opera and only moderately less uncomfortable on the concert platform. Add to this a tendency to exaggerate her achievements, including the likelihood of a fraudulent claim to the Hapsburg title of Kammersingerin, and the lack of artistic mettle is further tarnished by deceptive misrepresentation.

Indeed, some of the most interesting parts of Brownrigg’s book relate to the extent that Castles’ dubious career became a vehicle for interested parties to lambaste the reputation and character of Melba. Critical adulation of Castles equated to demeaning Melba. Brownrigg supplies copious reviews that praise Castles’ innate sound and her nervous schoolgirl stage presence, and that either implicitly or explicitly condemn a range of Melba’s supposed deficiencies, ranging from alleged moral slackness to vocal disengagement. Ultimately, however, Melba’s accomplishments, always supported by a ravishing talent, flourished, while the Castles movement, supporting a mediocre talent and even less of a genuine career, simply withered. There are, of course, risks in writing so detailed a biography about a central character whose major career achievement was failure. The most obvious risk is disengagement with the central character, made more likely by Castles’ own mature hand, as well as the hands of her proponents, in creating fabricated accomplishments and exaggerated abilities. What might be authorial intention to arouse sympathy for the manipulated plight of a simple country girl approaches erosion by the weight of evidence that Brownrigg presents suggesting that Castles was a fraudulent failure. One wonders where the ‘tragedy’ in this really lies.

Evidence there is in plenty. Perhaps because of the author’s background as an archivist and social historian, the book is crammed with reviews, letters, commentary and observations, to the extent that it sometimes reads like an explicatory critique of Castles’ critical reception. Long quotations from sources such as the Bulletin, the Freeman’s Journal and almost an entire chapter devoted to the views of the Yarrawonga Chronicle and the Goulburn Evening Penny Post certainly indicate a wealth of research, but they also give the book a decidedly thesisor academic paper-tone, which risks bogging down more central preoccupations about Castles herself.

Then there is the matter of what might be called the culture of music. It can be dangerous territory for non-musician authors to embark on musical insights and judgments. It must be conceded that Brownrigg traverses this cultural quicksand with some success. His portrait of Peter Dawson, for example, is alive, informed and engaging. Less comfortable is Brownrigg’s ignorance of the ongoing standing of such a major historical figure as the wondrous contralto Clara Butt: ‘if she is remembered at all today it is not for her singing.’ The playing of the great Teresa Carreño is tersely underestimated as ‘strenuous, flashy pianism’. One would also wish for a more exact account of the classifications of the soprano voice, in particular the musical uses of the terms ‘dramatic’ and ‘spinto’.

In general, this is a handsome book. Its research seems meticulously detailed, and the volume contains many fascinating illustrations relevant to Castles and her epoch, and many nuggets of cultural history. One does detect an historian’s training in the number of uses of ‘sic’ to correct the arguably laxer writing habits of that era. It is a pity therefore that the publishers were not similarly exact in such errors as ‘Bourke (sic) Rd Camberwell’, the pianist Victor ‘Buesst’ or ‘Buest’, or the garbled German in ‘eine schonsten Sopranstimmen … selten zu horen’ (all sic). Finally, one which I suspect Melba might have enjoyed: Ella Caspers ‘was the sister of composer Agnes Caspers and brother of the organist at St Mary’s Cathedral’.

Comments powered by CComment