- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

It is quite extraordinary how often in this country we resort to caricature in our cultural expression. Think of the hammy acting in Australian films and television, the switches in levels of reality in Patrick White’s novels and plays, the new lead William Dobell gave to modern Australian painting or Keith Looby designs for Wagner. Peter Carey has made his fortune from it; Bill Leak has made it his trademark. And no, we won’t start on the politicians, thank you.

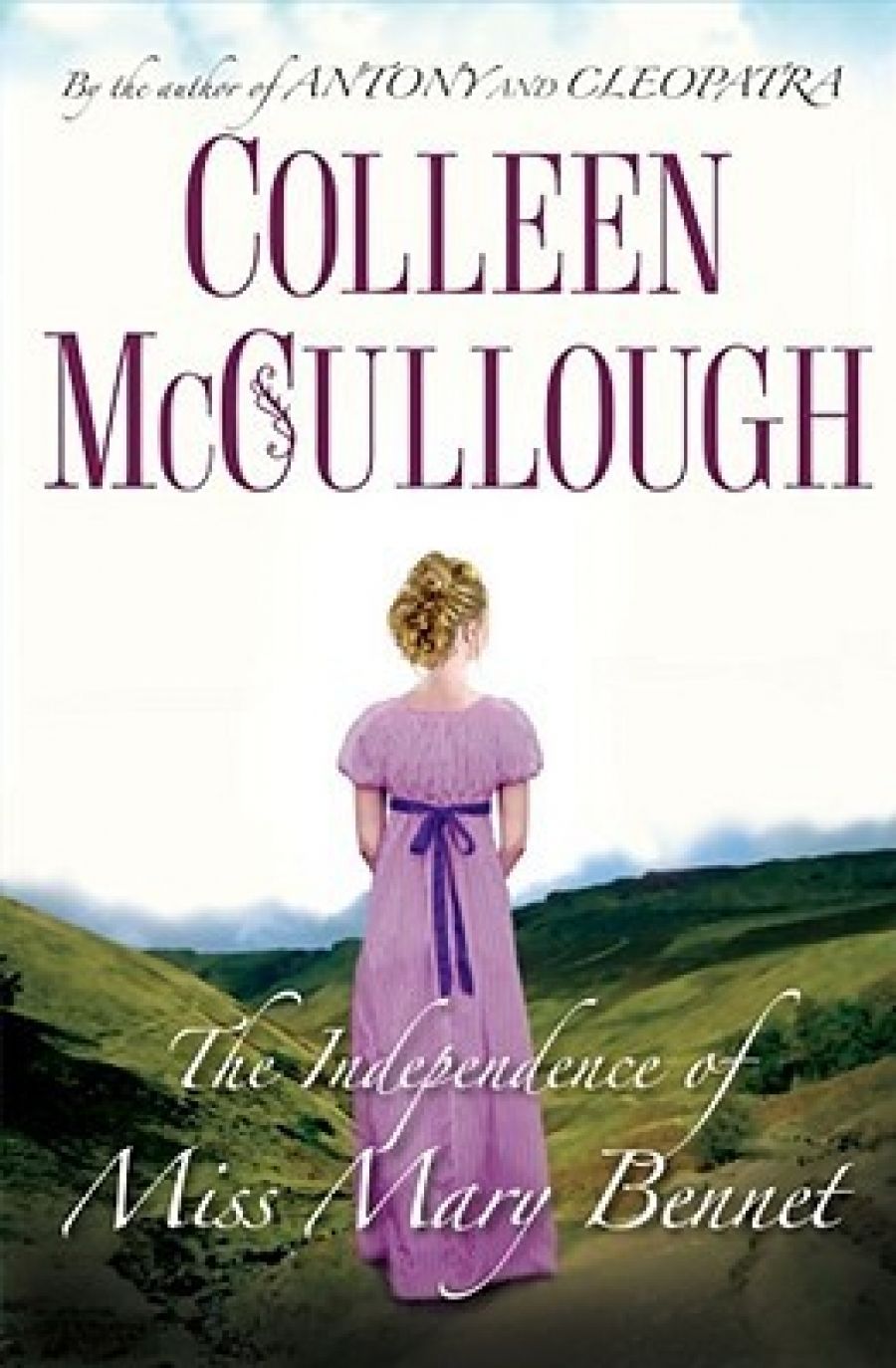

- Book 1 Title: The Independence of Miss Mary Bennet

- Book 1 Biblio: HarperCollins, $49.99 hb, 470 pp, 9780732287221

Something like these kinds of ruminations are triggered by Colleen McCullough’s latest book, in which she takes up the cudgels for Mary Bennet, the dullest and most insipid of the five Bennet sisters in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice (1813). I have to confess that I have not spent many restless nights wondering whatever happened to Mary. When I was a student, the essay ‘How Many Children Had Lady Macbeth?’ was required reading, as it hypothesised one of the cardinal critical fallacies we had to avoid. That was before Tom Stoppard turned such rigid purism inside out and upside down.

So McCullough has Mrs Bennet drop dead on page two, and Mary, who has been left to look after her for seventeen years, gets a life. In that time she has read everything she can lay her hands on, and has ranged considerably further than the pious literature which had made her youthful observations so banal.

The problem with taking up a Jane Austen character and working out her destiny is that there should be some sort of connection between the original and the sequel; more, that is, than just the names of the characters and the formal relations between them. You might expect something like an attempt at archness, if not fine irony, in the observation of the character. That is not McCullough’s way, though. Not for her Jane Austen’s ivory miniatures.

When Mary pours the tea she puts the milk in first, just like the staff below stairs. That is not what brought on her mother’s demise, but it is indicative of the missing refinements. When Mary reflects on the odious Mr Collins, she comforts herself that she has been ‘over that’ for twenty years. She is only one syllable from being so over it. The idiom is not high Regency, though on another occasion McCullough fusses over a parenthetical explanation of what a guinea is worth, without feeling called upon to explain what a reticule is for putting them in. She seems uncertain of just how many BBC bonnet and frills productions we have watched over the years, uncertain of what has to be explained and what can be taken as well known. Cliché is rampant: chaises inevitably bowl along; men pound their thighs (apparently without bruising).

McCullough is even more uncertain about expression. Mary, disgusted that Jane is pregnant yet again, wonders why her brother-in-law, Charles Bingley, doesn’t ‘plug it with a cork’. McCullough, like her subject, is so taken with this vulgarity that she comes back to it several times throughout the novel. It is one thing for Mary to be disturbingly frank in her opinions, but this kind of coarseness, and the saltiness of Lydia’s public outburst at Darcy’s dinner party, are (one is ashamed to admit) for the modern reader. They are unthinkable in Austen’s world, or any extension from it. So the question comes again: just what does McCullough want to achieve by this crudity? Is it a mockery, a reviling of the iconic status of Austen’s kind of writing, and of the world she writes about? If so, is coarseness the means to achieve that?

As for the story, it is bad form to give that away; but it involves the abduction of the resolutely independent Mary, her imprisonment in a caged cell in the caves beneath the Peak District, and a mad monk who keeps a workforce of children underground while he manufactures potions to sell in the neighbouring villages. He is a kind of alchemist. In other words, the story turns into the kind of Gothic melodrama that Austen burlesqued in Northanger Abbey (1818). But instead of this all being a broad literary joke, it is inescapably a rip-snorting bodice-ripper, with horses cantering through the countryside at night, cold-blooded murders, highwaymen and brothel keepers, and a cloyingly rapturous sexual reconciliation between Elizabeth and Darcy – the whole box and dice.

In the end, Father Dominus and the cowled Children of Jesus are more reminiscent of Snow White’s dwarves than anything else; and Mary’s situation as his enforced amanuensis is too melodramatic to be poignant. When the children are rescued from their slavery and temporarily housed in Pemberley’s splendid ballroom, the narrative descends into farce, as they poo and pee everywhere and avenge themselves on philanthropic intervention.

In one sense, the novel gets the period preoccupation right. It is the literary equivalent of a folly. It is, at times, quite a lot of fun. Its projection of what Mary might have turned into is actually quite interesting, but it carries an awful warning about where unsupervised reading can lead you.

Comments powered by CComment