- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘Ice is everywhere,’ observes the narrator of Ice, Louis Nowra’s fifth novel, before succumbing to a bad case of the Molly Blooms and giving us a few pages of punctuation-free interior monologue. No wonder he’s so worked up: ice, in Ice, really is everywhere. It is subject, motif, organising principle, and all-purpose metaphor; it is death, life, stasis, progress; it is seven types of ambiguity and then some. For variety’s sake, Nowra occasionally wheels out a non-frozen alternative – taxidermy, waxworks – but the design is clear: these are merely different nuclei around which the same cluster of metaphors gather.'

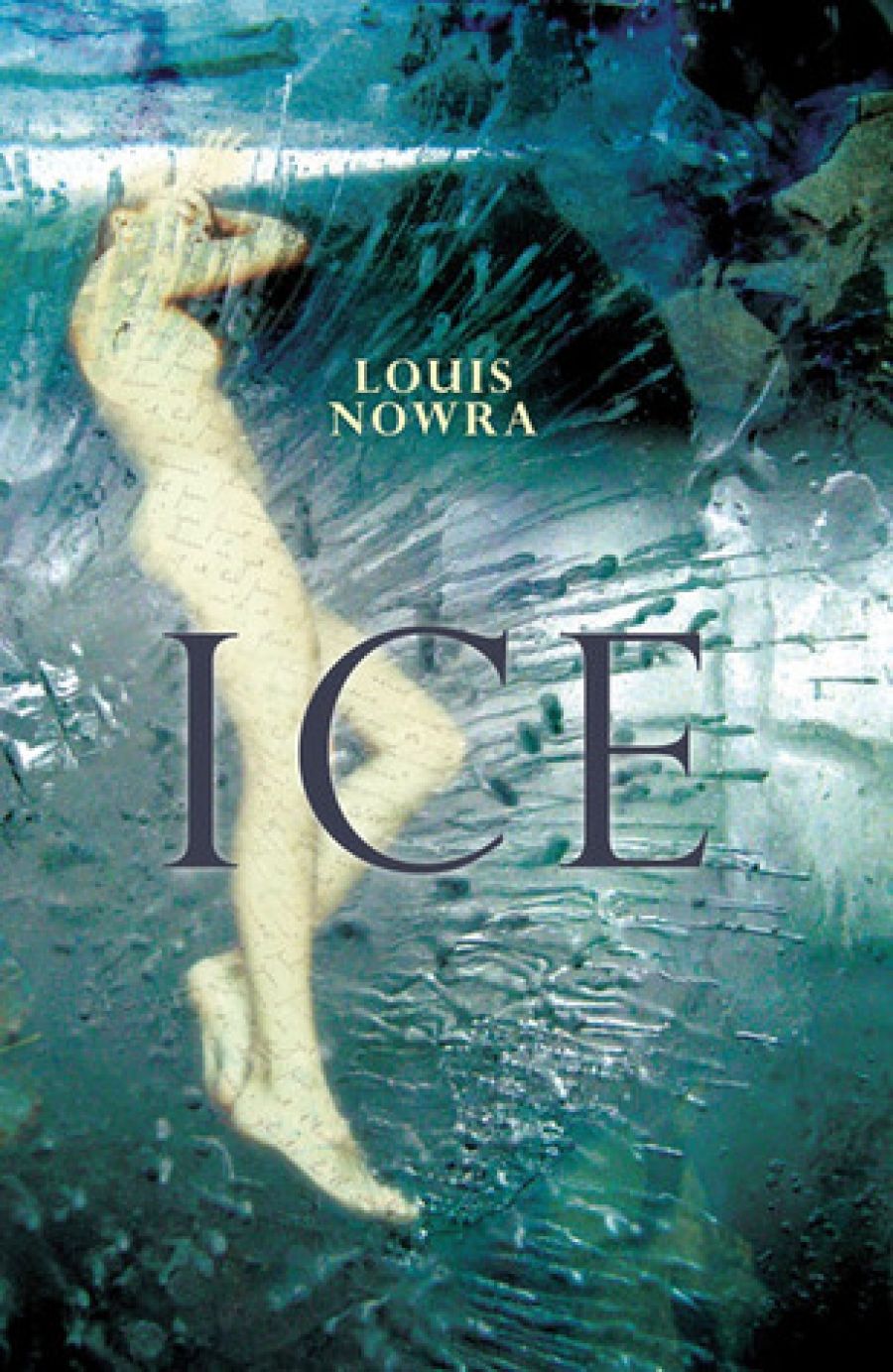

- Book 1 Title: Ice

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $32.95 pb, 336 pp, 9781741754834

Ice, preoccupied as it is with the eponymous substance and its metaphorical derivatives, could so easily have become just an exercise in ‘spot the motif’. Fortunately, Nowra is too canny a writer to serve up such journalistic and reductive fare. The narrator sees ice everywhere because, from his perspective, ice – in its various literal and metaphorical manifestations – is everywhere. Moreover, the story the narrator is engaged in telling is concerned with a parallel and still more pervasive ice fixation. Far from casting about for thematic unity, Nowra is instead skilfully drawing together form and content.

Ice begins with the spectacle of an iceberg being towed into colonial Sydney Harbour. The size and purity of the berg – ‘an incandescent block of corrosive light’ – stuns the assembled crowd into silence. Symbolism quickly accrues: Sydney’s lord mayor proclaims the iceberg an augur of coming democracy and civilisation; others see it in religious terms, as radiating ‘the effulgent light of heaven’. Soon, however, the imperatives of capitalism begin literally to chip away at the fast melting chunk of ice. Shards of iceberg become an ephemeral currency, and the city is briefly gripped by a kind of ice-drunkenness, its streets resembling ‘a riotous bacchanalia where God was forgotten and Australians had reverted to paganism’.

As the iceberg dissolves into the Harbour it discloses an enigma. At its core is the body of a young sailor, frozen in space and, it almost seems, in time. Malcolm McEacharn, one of the Scottish engineer–entrepreneurs behind the iceberg project, marvels ‘at the miraculous preservational qualities of ice’, and notes that, ‘although seemingly filled with life, [the sailor] was incapable of being resuscitated’.

This proves no idle observation. The narrative takes us back to Malcolm’s childhood fascination with ice and on to his marriage to Ann Pierson, the pagan daughter of a Yorkshire squire. The union carries an intense erotic charge to which Malcolm submits completely, allowing his ambition and curiosity to taper. However, less than a year into the marriage, Malcolm wakes one morning to find Ann still, as though sleeping, yet cold to the touch.

Malcolm is rescued from his subsequent boozy grief when he chances upon the scheme of a half-crazed ship’s captain to tow icebergs to Australia. Intrigued, Malcolm, along with his business partner, Andrew McIlwraith, becomes immersed in the project. The ostensible object is for the two men to impress the world with their audacity and ingenuity, but McIlwraith discerns in Malcolm a deeper motive: ‘The iceberg was the supreme gift [to Ann].’

The iceberg dissolves into the brine at Circular Quay and the sailor it has held in frozen captivity is released to its putrid fate on a coroner’s slab. Preservation of flesh becomes Malcolm’s – and the novel’s – guiding concern. Malcolm, a man of science, explores man-made means of preservation, dabbling in primitive ice machines, taxidermy, embalming. Flesh must not rot; memory must be given corporeal form. Like some latter-day Victor Frankenstein, Malcolm experiments with electricity as a means of reanimating dead tissue. Suspended animation vouchsafes memory but the effect is bitter-sweet, offering the illusion of continued life but lacking the warm actuality.

Nowra’s complex intertwining of motif and metaphor is given further depth by a modern-day subplot involving the narrator, Rowan, and his wife, Beatrice, who lies comatose in a hospital bed, the victim of a savage and random act of violence. Distraught and incapable of influencing the concrete reality of Beatrice’s situation, Rowan vows to complete the biography of Malcolm McEacharn that she was working on prior to the assault. Rowan, like Malcolm, is interring his lost love in the ‘mythical country of ice’, which, in Rowan’s case, also happens to be the mythical country of Ice.

Malcolm McEacharn and Andrew McIlwraith are historical figures, and we can assume that Beatrice intended her biography of Malcolm as a sober, factual work. Rowan’s Ice cleaves close to history but makes excursions into psychological speculation and fantasy, albeit fantasy of the most grounded, non-escapist variety. What at first appears to be a kind of low-wattage magic realism (the iceberg, the frozen sailor) turns out to be a tale of despair constructed by a mind derailed by grief. Rowan’s sorrowful apostrophes to his unconscious wife echo Malcolm’s post-mortem letters to Ann, just as Ice parallels Malcolm’s attempts to incarnate and memorialise his wife in ways that can only fall short.

Nowra’s handling of the intertwined narratives is masterful and, with one minor exception, the many ice and ice-related motifs and metaphors gel nicely. Ice is a strange and skilful novel, and, contra its title, so warm, so alive.

Comments powered by CComment