- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

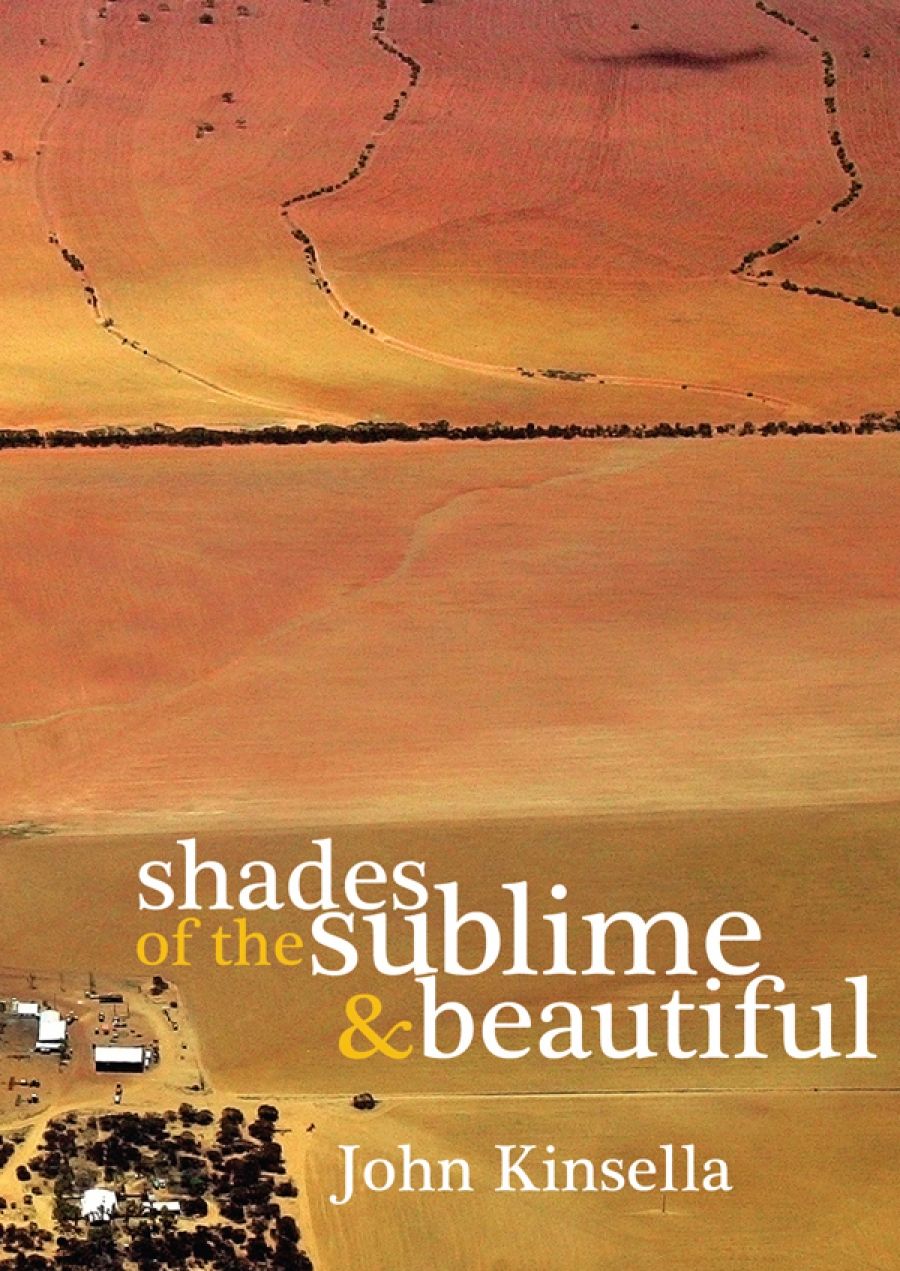

Another poet might invoke Edmund Burke’s famous treatise on the Sublime and the Beautiful as a piece of phraseology or a pleasing adornment, but with John Kinsella, such a title is dead serious. Elliot Perlman’s superb novel Seven Types of Ambiguity (2003) ingeniously makes the reader think of William Empson’s, and the idea of plural signification it evokes, but not instantly to reread it. Kinsella’s use of Burke’s title prompts one to reread the original – ideally, in a Kinsellan métier, on the internet, late at night. Additionally, the ‘shades’ in Kinsella’s title is an important supplement – shades as variations, colourings, but also shadows, undertones.

- Book 1 Title: Shades of the Sublime and the Beautiful

- Book 1 Biblio: Fremantle Press, $24.95 pb, 111 pp, 9781921361098

The public image of Kinsella remains that of an innovator and prodigious enfant terrible. But this volume demands that we enlarge and reframe this image; Kinsella emerges as not just an innovator but as an intellectual, with a tinge of sagacity inflecting his still-buoyant energy and verve. Kinsella joins Les Murray and Kevin Hart as Australian poets of world prominence who are ‘professorial’ in the best sense – poets to whom the reader looks not just for verbal ingenuity but for conceptual wisdom, and who all also have an instructive gentleness which studs their brilliance and cogency. Kinsella is adamantly avant-garde, a crucial gesture which has prevented Australian poetry of the past generation from being tempted to ‘move beyond’ modernism or to synthesise it into a new conformism. But Kinsella is also a very referential poet, though his referentiality is often indirect. As the poet says, speaking in the first instance of his grandfather, ‘Kinsella is an overlay’. But the poet is still talking about ‘topics’ (in the root sense of the word, given Kinsella’s preoccupation with place) that the reader can understand. One suspects that, in Australia, the term ‘mature’ as a gesture of critical approbation still sounds reminiscent of S.L. Goldberg, but this collection is a new clearing for Kinsella, a vigorous reckoning of fresh prospects. Excessive energy has been spent in encomiastic or castigating responses to Kinsella’s work; not enough on analysis. The tenacious passion of this volume demands this more concerted attention.

Kinsella’s understanding of the sublime and the beautiful is in line with recent moves in Romanticist criticism, where the elevation of the sublime as somehow both a straightforwardly grand and vertiginously deconstructive trope has yielded to an awareness that the powers of the sublime are mediated and that the ‘proportion’ of the beautiful, can be asymmetrical indeed, as the work of Susan Stewart – with whom Kinsella has collaborated – demonstrates. Nor is the beautiful as well behaved or as determinate as we picture it, instead of the pleasingly trimmed hedgerow that Kinsella describes as ‘a screen full of triangles / gone suddenly blank’. Kinsella is also attuned to the ‘racism of the Sublime’, the way theoretical invocations of ‘astonishment’ beyond representation often unconsciously privilege a white noumenality.

In our age, Burke’s association of the sublime with fear and terror generates more than a frisson. Citing the 7 July 2005 bombings in London, Kinsella muses: ‘We sympathise with those who suffer having suffered ourselves / We “delight”? We watch vicarious.’ Kinsella also solicits terror’s seeming obverse, the sacred: ‘The snakes, restless / whisper in their stillness, / What I’ve always heard as Deo favente.’ Kinsella, Murray, and Hart all have very different positions on religion; Between them, they comprise the serious, range of positions on this subject available today. But in all three cases spirituality is a defining issue. That Kinsella’s stance is respectfully yet resolutely non-Christian should not occlude this fact.

For Kinsella, the West Australian landscape puts European aesthetic categories into question, or at least provides a new tableau for their enactment. The landscape poems in this volume image the ochre and parrots of the wheatbelt, familiar to Kinsella’s admirers. Kinsella assays the various senses of the wheatbelt, attending to each in turn but also conjuring an associative synaesthesia, reaching an unnerving peak as the poet listens ‘calmly to AC/DC’s Highway to Hell, white gums equivocal in smoke, pall’.

The juxtaposition of the intense and the obdurately strange here prompts recourse to Alain Badiou’s idea of the multiple: a condition irreducibly plural, ‘partitive’, but also the only manifestation which does not end up being chimerical the way postulated unities always are. Kinsella also, in ‘Terror’, displays a Badiouesque sense of the imaginative possibilities of the mathematical.

For Kinsella, what limits is also what generates potentialities for breakout. In ‘Clearance’, a grim picture of small-town life, is followed by involved opening:

Sky-flex falsifies perception, so fixed on

Windscreens, windows, telescope sights, portals,

Divination: they take the straight and narrow

Out of … here; fixate.

‘Fixate’ is a verb, an imperative to look beyond the given that destabilises the ordinary idea of a fixated gaze, being a merely pinioned one. But fixate is also adjectival here, in the sense that a non-moving state is a ‘fixate’ one. Yet Kinsella reveals ‘the fixate’ as always suffused with motility.

In the soaring ‘Lover’s Leap’, Kinsella quotes Burke as finding, in unfinished sketches, ‘something which pleased me beyond the best finishing’. Kinsella’s poems are not incomplete because of their sketchiness but because of their plurality, yet they also shimmer with unfinished potential. They demonstrate how poetry can parade a lack of plenitude, how privation can nonetheless ‘fixate’ transcendence.

Comments powered by CComment