- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

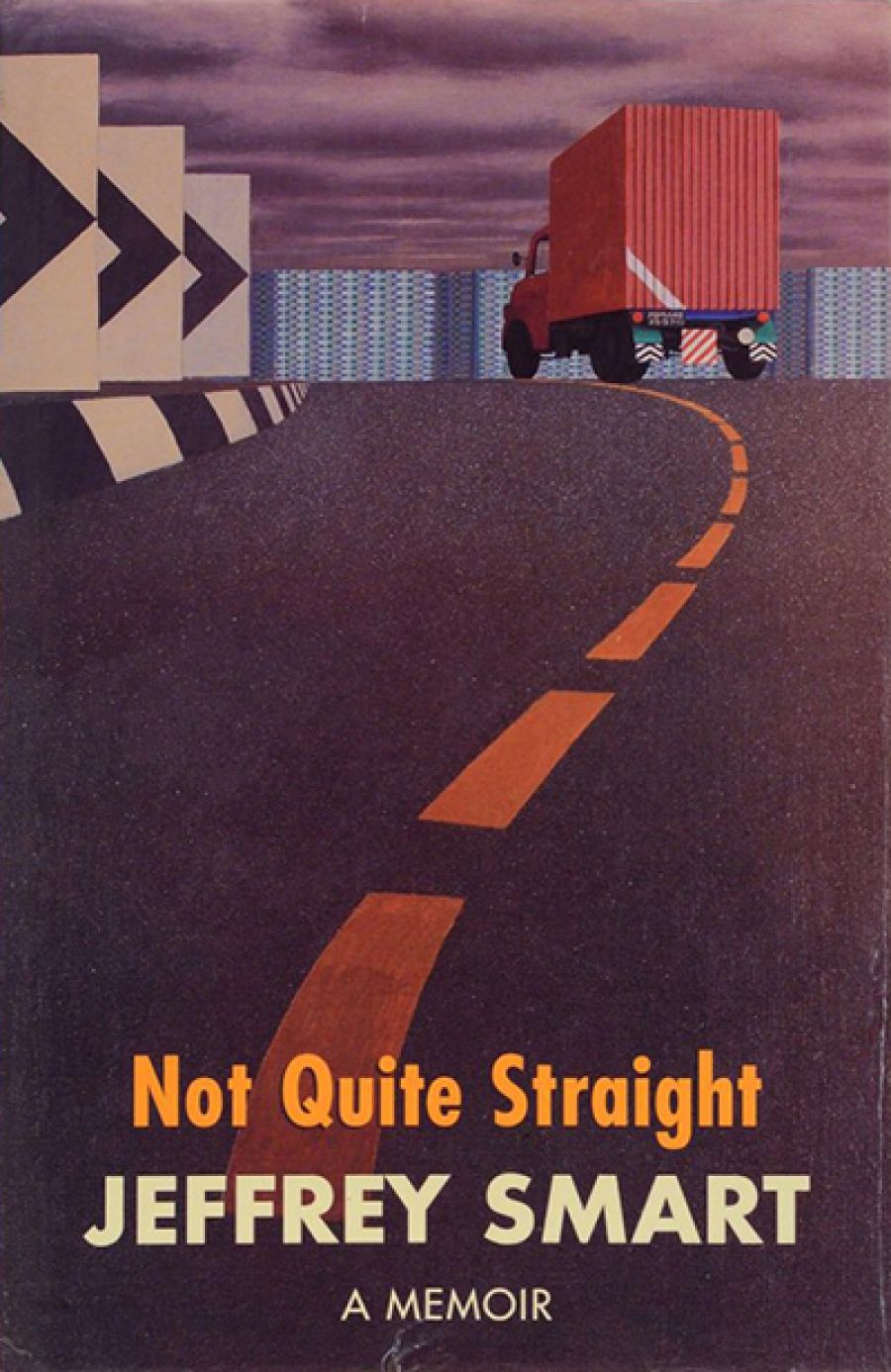

- Book 1 Title: Not Quite Straight

- Book 1 Subtitle: A memoir

- Book 1 Biblio: Vintage, $24.95 pb, 468 pp, 978174166 6274

I recently travelled by bus from Canberra to Sydney to interview Smart while he was revisiting Australia from his adopted home in Italy, so those lushly stark vignettes of the modern city and its hinterland that have become his hallmark were to the forefront of my mind. How uncannily they blended, I continually sensed, with the passing succession of views framed by the bus’s windows. Down to the smallest details – the arrows painted on the road, the corrugations of a metal fence, the artless graffiti on a factory wall, the patterning of rivets on an overtaking truck – it was as if such quotidian features of our visual diet had all been conceived and designed by Jeffrey Smart for our unwonted contemplation, as in any number of his canvases. Trompe l’oeil rampant: so much so that the illusion works in two directions. The reality assumes the guise of the art as much as the art assumes the guise of reality, so that any conventional distinctions between the two are unsettlingly called into question.

In another context, poet and critic Charles Simic recently observed in the London Review of Books (20 March 2008) that ‘art doesn’t represent reality, imitate life, or copy nature. Experience is primarily an aesthetic matter.’ But it usually takes an artist, in whatever medium or genre, to keep alerting us to this and to insist on confronting us with it.

Without pretensions to being an artist in any verbal medium (he expressly distinguishes himself from such), Smart was almost bound to disappoint fans of his paintings when it came to producing his memoir of 1996, Not Quite Straight. (See, notably, David Marr’s exasperated review in ABR, November 1996.) Neither in the tale nor the telling of Smart’s own ‘experience’ here is there much you could call ‘aesthetic’. Fitfully, all but incidentally, he drops some tantalising hints about the artistic or literary influences on the development of his work and sensibility, and alludes to some detail of his professional technique, his work routine or his chosen subject matter. But he appears more concerned to drop the names of celebrities past and present whose path he’s crossed at various stages of his life, and to rehearse the sexual enticements of a succession of more or less obliging younger men. There is a poignant sense of transience to such moments, as he records them here, and also of thwartedness: the opportunities he had, but just missed, for meeting yet other famous ‘names’ still haunt him down the years; strike him as ‘tragic’ in the case of an aborted dinner date with Marlene Dietrich in the early 1950s. But the piling up of such hits and misses is no way to give any sense of structure, proportion, shape, form, or disciplined composition to the writing – the qualities that are so radiantly impressive in his painting – and the cumulative effect is desultory in the extreme, where not (inadvertently) comic.

What’s frustrating about this for readers is that there are occasional signs of real verbal flair (in such pungent phrases as ‘rumoured to be vegetarians’ or ‘a Bloomsbury bacchanal’) and of a capacity for set pieces that can grip without recourse to social and sexual chit-chat. Smart’s nightmarish evocation of his stint as a ‘pantry boy’ aboard a ship travelling to Europe via North America has something of the intensity of Dickens’s or Conrad’s darker chronicles. He manages to stretch this across nine chapters; it’s a Gothic mini-saga that completely avoids his ritual invocation of the rich and famous, though they have a way of creeping back in to his reports of the onshore interludes en route, and not untypically when he misses out on meeting them: ‘I had friends here [Philadelphia] to whom I had written. The conductor Eugene Ormandy was one … Alas, Mr Ormandy was away on tour …’ Alas, alas!

‘I feel that perhaps my painting is better than ever before,’ Smart tells us on a more upbeat note at the start of his ‘Postscript’ to the just-released paperback edition of his memoir. But characteristically he recoils from dwelling on this subject of his creativity and proceeds to reflect on the costs and pleasures of celebrity, including his own. Why his obsession with this subject, I felt comfortable enough to ask at the end of our interview (which had mainly centred on his association with fellow-painter Donald Friend, the subject of my current research). The answer had more to do with modesty than with what he aptly calls in the postscript his ‘assumed pomposity’ (emphasis mine). He seemed genuinely taken aback by my imputation of name-dropping, and indicated (not disingenuously, I felt) that he simply thought the names in question would be the chief source of interest for audiences of the book. This chimes with his belief, articulated in the new postscript, that the subject of his own work and its recent success would be ‘too boring’. The sad irony remains that if (in the words of David Marr’s original review) Smart had ‘risk[ed] boring us’ more, he might have ended up disappointing us less. Two of us, at least.

Comments powered by CComment