- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘With a few strokes’

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

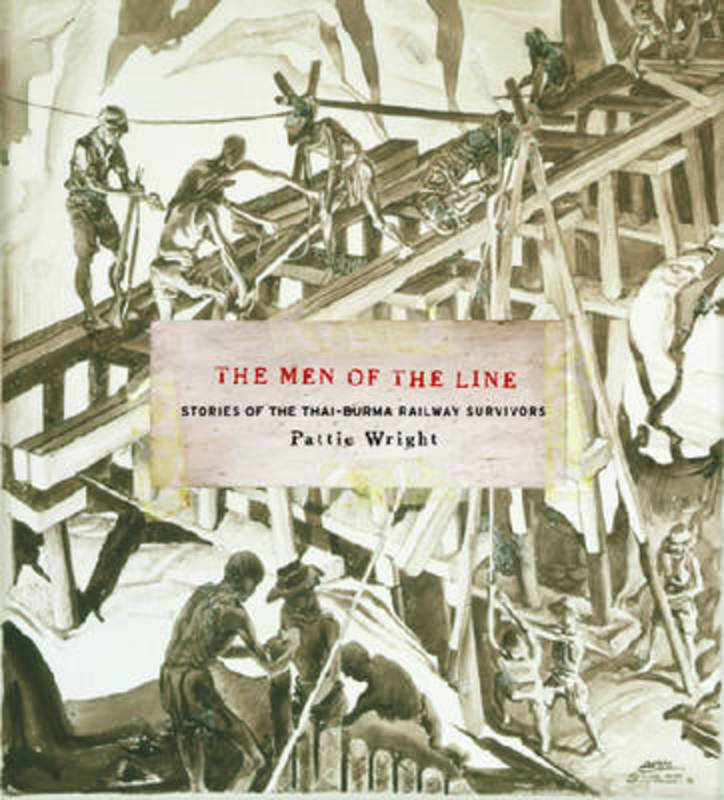

These two books on the building of the Thai–Burma railway in World War II are very different in format and tone. Australian film-maker Patti Wright’s Men of the Line is an exquisitely designed collection of stories and images by Australian prisoners of war who were forced to build the railway for their Japanese captors. Wright describes her book as ‘a tribute to the ex-POWs who experienced the best and worst that human nature can offer and returned to tell the tale’. Canadian journalist Robin Rowland’s A River Kwai Story: The Sonkrai Tribunal is a solidly researched investigation that concentrates on F Force, the group of Australian and British prisoners that suffered the worst death rate on the railway, and the postwar war crimes trial that found seven Japanese soldiers guilty of the ‘inhumane treatment’ of these men. Rowland concludes that the Japanese did commit war crimes; she also exposes failures by Australian and British officers that increased the POWs’ suffering.

- Book 1 Title: A River Kwai Story

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Sonkrai Tribunal

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $35 pb, 416 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Title: The Men of the Line

- Book 2 Subtitle: The Sonkrai Tribunal

- Book 2 Biblio: Miegunyah, $45 hb, 302 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

Despite these differences, both books share a sense of urgency based on current concerns. As Wright told the audience at her book launch just before Anzac Day, her aim was to collect ‘the authentic voices of the railway before they all left us’. For Rowland, the F Force war crimes trials are an indictment of the Bush administration’s policy of not applying the Geneva Convention to prisoners captured in the ‘Global War on Terror’. In 2002, Alberto Gonzales, legal counsel to President George W. Bush (and later Bush’s attorney-general), argued for ignoring the Geneva Convention because terms in it, such as ‘inhumane treatment’, had never been legally defined. As Rowland states, Gonzales, ‘with a few strokes of his computer keyboard’, erased the definition of ‘inhumane treatment’ that had been established in the F Force and other trials following World War II.

The anecdotes in Men of the Line are organised according to the work camp along the railway in which they occurred and are a mixture of humour, tragedy and poignancy. Arch Flanagan relates that his ‘saddest memory’ of his imprisonment was when Japanese soldiers pulled a sick Sergeant Mickie Hallam out of his hospital bed and bashed him to death because the men in the working party under his control had shirked labour. The stories are often powerful, yet they have been decontextualised; the book fails to evoke the Australia of more than sixty years ago in which these men lived, and from which they went into captivity.

The sheer bewilderment that Australian soldiers felt on being defeated and taken prisoner by the Japanese cannot be understood unless one understands the importance of race to the Australian identity in 1942. Australians believed they were racially superior to Asians. The humiliation these white men felt at being forced to labour for non-whites cannot be underestimated. Betty Jeffrey’s 1954 memoir of her captivity by the Japanese – one of earliest to be published – summed up this inversion in its title White Coolies.

The racial nature of the war against the Japanese meant that Australians were more brutal toward this Asian enemy than they were towards their German and Italian foes. The killing by Australian soldiers of wounded Japanese during the New Guinea campaign was sufficiently common that war artist Ivor Hele made a drawing in 1943 entitled Shooting Wounded Japanese, Timbered Knoll. Mark Johnston notes in Fighting the Enemy: Australian Soldiers and Their Adversaries in World War II (2000) that Australian troops continually refused to take surrendering Japanese prisoners, to the dismay of intelligence officers who wanted to interrogate them for vital information. One officer of the 2/3rd Battalion was forced to tie a Japanese prisoner to himself for two days in order to prevent soldiers from killing him.

Another key to understanding the stories in Men of the Line is the fact that the Japanese overwhelmingly defeated the Australian and other British Empire forces in Malaya and Singapore. The defeat cannot be entirely blamed on the British. Gordon Bennett, an Australian general, had command of all the forces in southern Malaya, but, as John Coates comments in his Atlas of Australia’s Wars (2006), his plan was ‘flawed from the start’ and the Japanese easily broke through his defences. Nor were the Australians part of an outnumbered force. It is normally considered that an attacking force needs to be larger than the defending force by a ratio of two or three to one. In Malaya, three Japanese divisions attacked and defeated a defending British Empire force equivalent to four (later five) divisions.

The stunning nature of the Japanese victory led many Australian soldiers to lose respect for senior Australian officers. One officer the soldiers particularly hated was Lieutenant-Colonel Gus Kappe, the 8th Division’s chief signals officer, who later commanded the Australian component of F Force on the Thai–Burma railway. This context is important for understanding Max Robinson’s story in Men of the Line. Robinson was a signaller and therefore had experienced the blustering Kappe as his commanding officer before the fall of Singapore. Kappe appears in Robinson’s story of the railway as an immaculately dressed officer who suddenly appears as the men are pile-driving while constructing a bridge. When a soldier rebukes Kappe, he threatens to put the man on a disciplinary charge. Robinson implicitly contrasts Kappe’s behaviour with two junior officers, Adrian Curlewis, who ‘worked as hard as any of us’, and Ben Barnett, who ‘was respected for what he did up there’.

Lieutenant-Colonel Kappe also features in River Kwai Story, where Rowland describes him as ‘an ineffective commanding officer’ who ‘deserted his own men’. After the war, when Kappe gave evidence during the trial of seven Japanese soldiers for war crimes committed against the men of F Force, he committed perjury at least twice in order to exaggerate his role in protecting POWs, Rowland finds. River Kwai Story argues that the seven Japanese were rightly convicted of war crimes, but adds that actions by Kappe and the senior British officers contributed to F Force’s high death toll. In an intriguing appendix, Rowland considers to what extent Pierre Boulle based his novel The Bridge over the River Kwai (1952) on real events. Rowland argues that F Force provided the model for the prisoners in the novel. He even suggests that The Bridge over the River Kwai’s main character Colonel Nicholson (played by Alec Guinness in the film version) was partially based on Kappe.

Men of the Line and River Kwai Story are part of the current publishing boom in books about Australia in World War II that is indicative of two trends. The first is an increasing interest in the Pacific War, which historian Peter Stanley sees as an attempt by modern Australia to find meaning in World War II by re-conceiving it, not as a worldwide struggle against tyranny but as a battle in which Australia defended itself in its own region. The second is a realisation that the World War II generation is declining. For younger Australians this means an increased interest in these men and women’s stories; for the veterans it means an increased willingness to tell their stories. As Arch Flanagan says in Men of the Line: ‘When I came back, I just got back on with my life. But now, more and more with my retirement and as I get older, I’ve become obsessed with thoughts of those who died up there.’

Comments powered by CComment