- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Hoppy the hero

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

My memory of John Hopkins – in fact, the memories of most of my generation of Australian music-lovers – goes back to the Proms he conducted in Sydney and then Melbourne from the mid 1960s to the early 1970s. Hopkins was, to young audiences of the day, an anti-establishment musician who dared to strip the furniture from the stalls and, in the process, also strip away what he calls the ‘dynamic conservatism’ of the then Australian Broadcasting Commission. ‘Hoppy’, as he was known, was a hero – the Sir Henry Wood of the Great Southern Land. He was, after all, English, with a broad Yorkshire accent.

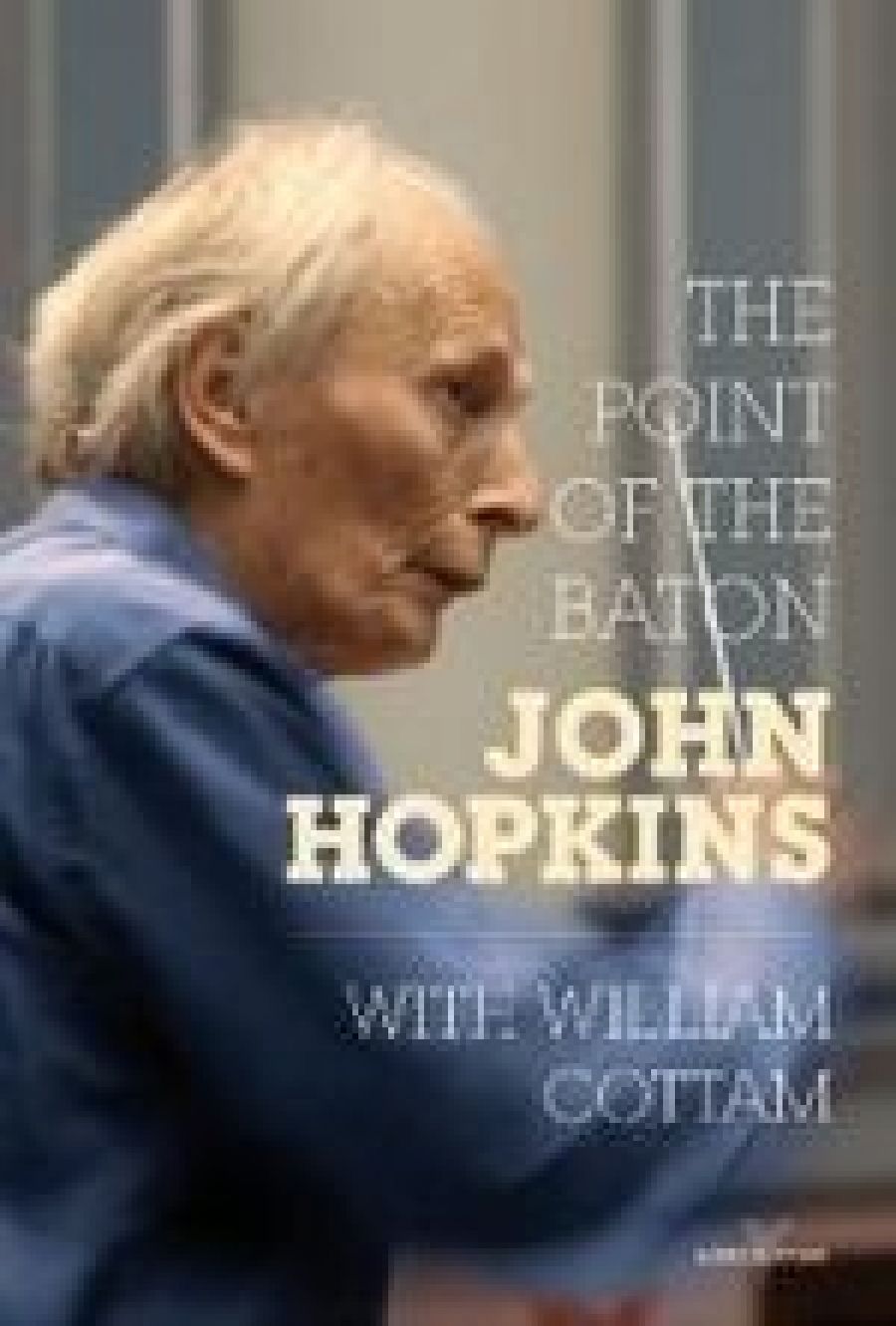

- Book 1 Title: The Point of the Baton

- Book 1 Subtitle: Memoir of a conductor

- Book 1 Biblio: Lyrebird Press, $66 pb, 259 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

The Proms were astonishing for their period. How Hopkins, who was also the ABC’s federal director of music, persuaded and cajoled his lords and masters into territory other than the well-ploughed furrows of the ‘celebrity concerts’ of the time is indeed something to be admired; even forty years on, this has to be seen as a masterstroke. Subscription audiences, he recalls, ‘knew what they liked and liked what they knew’, but Hoppy at least tried to persuade them or their descendants to know a little more and, perhaps, to like it a little more.

That tuxedo I remember well. As Hopkins himself recalls, in this witty and wise account of a long life in music, when he walked on to the Melbourne Town Hall stage with the leader of the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, Leonard Dommett, who was similarly dressed, someone from the audience called out, ‘Guess who’s Mum’s got a Whirlpool!’

Of course, the ABC knew better, didn’t it? By 1975, John Hopkins had left the commission to set up the school of music at the Victorian College of the Arts (an institution he was later to run, only to return to the music school), but was still keen to be involved with the Proms, at least in Sydney and Melbourne. Whereupon he was told he would share the podium with – if it can be imagined – Willi Boskovsky, who would bring a touch of the Danube to the Yarra and Harbourside. After this unpalatable mixture of schnapps and Stockhausen, the traditional queuing system was abolished; then the ABC decided that adorning the hall was a needless expense. Just look at the enduring and endearing survival of the BBC Proms (b.1895) and weep for the Australian ones, which died in 1975.

Not for nothing does Hopkins devote a chapter or more to what he calls ‘The ABC Cage’. It is the most fascinating part of this book in that it proves the infuriating obduracy on the part of the commission and individuals that has always dogged the national broad-caster. One conductor, on asking who allowed a musician to go missing and being told ‘Sydney did’, said, ‘Who’s Sydney?’ If the ABC had been an orchestra, it would have been understaffed, ignorant and out of tune. Yet Hopkins persevered and occasionally won. This tenacity, essential for a conductor, also served him well as an administrator and educator in Melbourne and, later, as director of the Sydney Conservatorium.

For an Englishman, Hopkins has spent little time in his homeland. He came to Australia in the early 1960s, after six years in New Zealand, arriving straight into the world of the late, great Sir Charles Moses, champion woodchopper and musician manqué, who ran the commission like Henry Wood ran the Proms. Moses was welcoming to the young English conductor, visiting his home with the soprano Rita Streich in the front seat and his axes in the boot, and encouraging his ideas; not so Moses’s successor as general manager, Talbot Duckmanton, who would reject Hopkins’s ideas on grounds of bureaucratic jealousy rather than idealism. When Hopkins proposed a national FM classical network, Duckmanton responded that he had gone too far, accusing him of arrogance.

I wish Hopkins had included more about his time at the ABC and perhaps less about his early days in England and New Zealand. A little too often there is superfluous detail that gets in the way of more interesting and profound occurrences. Great soloists, conductors and composers wander in, as if summoned from the wings of recollection, only to disappear before we have a chance to get to know them. Encounters with Shostakovich and Stravinsky flash by, yet a whole chapter is devoted to Hopkins’s association with Kiri Te Kanawa.

There are a few admirably pertinent thoughts on music and, especially, conducting. One of these observations, made at a time when the young Hopkins was studying at the Guildhall in London, is worth quoting at length, for it informs not only what he was to become but also helps to define and explain the mystical art that is his life’s work:

I would discover that one of the most important aspects of music is the creation of an orchestra’s special sound, and that the conductor is the catalyst for this sound. When a conductor has a clear picture of the sound he desires, his gestures and his whole approach to the orchestra lead the players in creating this sound. There are a lot of psychological aspects to the work of creating this sound, and an orchestra can feel these and will play because it enjoys producing what the conductor desires in the sound … The idea, the feeling, this creation of the sound the conductor sees and hears in his mind, is that subtle but critical thing he must convey to the players.

Elsewhere are more personal recollections of Hopkins’s family, especially his beloved wife, Rosemary, mother of his five daughters, who died of cancer at the age of fifty-one and, being a Christian Scientist, did not seek medical advice until it was too late. Hopkins writes well and pertinently of his questionings of Christian Science belief, especially in the light of his own illnesses. He also writes interestingly of his various travels, including to Soviet Russia and, more recently, South Africa.

‘Eye contact, while subtle, is enormously important in establishing the connection between a conductor and orchestra,’ he writes towards the end of the book. Now in his early eighties and living in Melbourne, Hopkins still pursues an active career. He attends many concerts and passes on his knowledge to a select group of students. I like that idea of eye contact. Certainly, it took someone like John Hopkins to look Australian music in the eye, and we owe him a tremendous amount for it.

Comments powered by CComment