- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: First among equals

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In the epilogue to the latest, massive contribution to his populist and nationalist enterprise, Charles Kingsford Smith and Those Magnificent Men, Peter FitzSimons laments that ‘the true glory days of the pilot are substantially gone’. He charts an heroic, pioneering age of aviation. The ‘magnificent men [in their flying machines]’ include not only the Australians, Kingsford Smith and his partner Charles Ulm, but the German Manfred von Richtofen, the Dutchman Anthony Fokker, the Frenchmen Louis Blériot and Charles Nungesser. Most of them saw service in the first aerial combats, above the trenches of the Western Front in the Great War. Kingsford Smith, a dismounted motor-bike despatch rider at Gallipoli, was accepted into the Royal Flying Corps. He called this ‘the chance of my flying life, and it was a decision I made without a moment’s hesitation’.

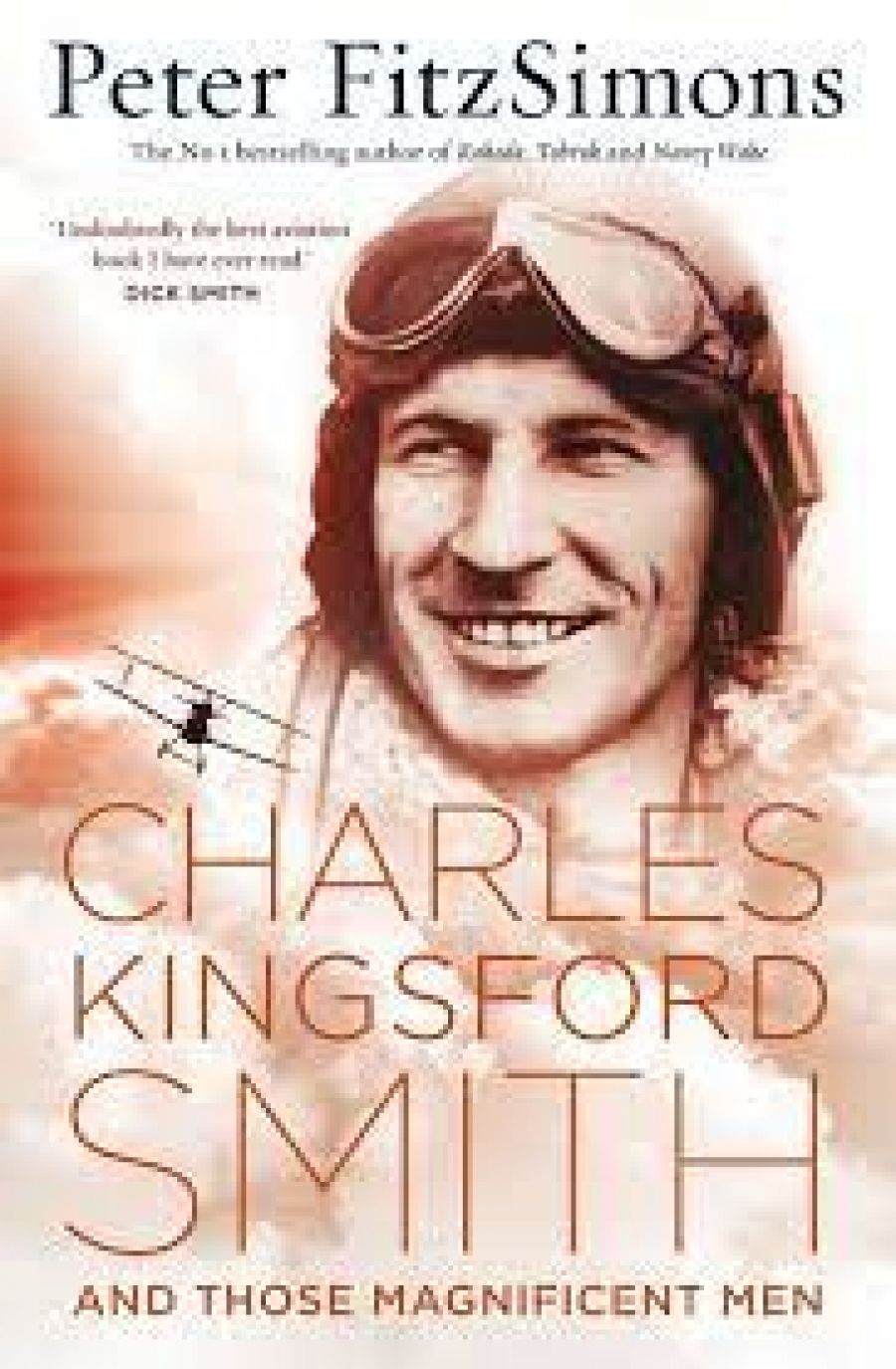

- Book 1 Title: Charles Kingsford Smith and Those Magnificent Men

- Book 1 Biblio: HarperCollins, $49.99 hb, 679 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

For FitzSimons, the chance to write another biography of a fabled Australian – following, among others, Steve Waugh and Les Darcy, besides their legendary countrymen en masse at Tobruk and Kokoda – came in March 2007. He was asked ‘to have a cup of coffee with a couple of blokes who wanted to make a documentary about Charles Kingsford Smith’. With a speed that his subject would have admired, the job was done in two years. Here was the story both of an ‘iconic figure’ and the ‘wonderful sagas’ in which he and fellow pilots featured. FitzSimons’s laudable aim was ‘to have Kingsford Smith and his companions fly again’. He drew on many secondary sources to produce ‘end-noted fact’, but also on ‘judicious use of the poetic licence I keep in my wallet’. If, sadly, that is not the end of the ordinary jokes in a long book, FitzSimons had a rich field in which to work, replete with reckless endeavour, improbable survivals and, more often, disasters.

He quotes Kingsford Smith’s resonant declaration that ‘I came into the world of flying at its dawn, and what a glorious dawn’. This was the era of experiment in aircraft design, the instantly vicious use of aerial warfare, exploration of how far and where rudimentary planes could fly, and of the purposes for which such feats could be exploited. One constant narrative line in the book is the adaptation of adventure to commerce, beginning with the use of pilots’ skills to develop aerial networks to deliver mail and passengers, first in modest numbers and over short distances, ultimately across oceans and around the world. Kingsford Smith, as FitzSimons convinces us by vivid and technically detailed episodes, was a great pilot. His ability to endure danger and discomfort, foul weather and mechanical breakdown was legendary. Thus another Australian larrikin was eventually promoted to wing commander and a postage stamp, knighted, and had Sydney airport named after him.

Kingsford Smith’s father was a bank manager who went broke after guaranteeing a dud loan. The family moved to Canada before settling in Sydney, where Kingsford Smith had been born in 1897. As did many thousands, Kingsford Smith talked his parents into letting him join the First AIF. In the RFC, he received a British commission and the Military Cross, boasted to his mum of ‘[bagging] my first Hun’, was shot down and lost two toes, and survived the most lethal branch of any Great War service. The war made him a pilot. In civilian life, flying – especially record-breaking – was the basis of his fame, if never ofa fortune that he held on to for long.

FitzSimons’s Kingsford Smith is first among equals as a pilot. His greatest triumph, the first-ever crossing of the Pacific by plane, partnered by Ulm, Harry Lyon and Jim Warner, was almost stymied for lack of funds. At various times, Kingsford Smith worked for other airlines than his own. He also made money by barnstorming, stunt flying, offering joy rides for those uninitiated in the air. In important respects, he does resemble the heroes of saga – the solitary venturer, brave beyond reason, fabled for his exploits, yet trammelled by the demands of smaller men, whether these involved money, politics or both. Kingsford Smith was, for FitzSimons, ‘that wonderful, laughing man – so full of energy, fun, vitality, charisma, derring-do, wisecracks, courage, vigour’. However, like so many other ‘flyers of daring’ – from von Richtofen to Bert Hinkler and Ulm – he would die flying, perishing somewhere in Burma, late in 1934.

There is much to applaud in FitzSimons’s book: the cameo from Harry Houdini at Diggers Rest, outside Melbourne; the future George V whispering to the dying king that his horse, Witch of the Air, had won at Kempton; the extramarital misbehaviour of Hinkler and Charles Lindbergh. On a larger scale, the forced landing of the Southern Cross in outback Western Australia, from which Kingsford Smith and his crew nearly perished, and after which his estranged friend, Keith Anderson, died trying to find them, is strongly told. The aftermath was obloquy for yesterday’s hero, although an inquiry exonerated Kingsford Smith and Ulm. Bill Taylor’s feat in saving Kingsford Smith’s plane in a flight from New Zealand – by climbing onto the horizontal strut to drain oil from a damaged engine to feed into the one still working – is a Boys’ Own tale of daring. FitzSimons tells it straight, to maximum effect. It is a pity that so often he does not.

His prose is splattered with italics, exclamation marks, repetition and capital letters, emphases suggesting that he has little faith in his abilities as a writer or that this book would have more fairly presented itself as Young Adult fiction, or as a distended comic. Puerility is everywhere. There are inept similes – Kingsford Smith is born with ‘a face like a dropped pie’ (no source given) – sallies of schoolboy French and German at the Voila and Maintenant level – a Pacific Ocean that is ‘majestic’ one moment, ‘mighty’ twelve pages later. Historical fabrication has the dying Austrian archduke ‘[gurgle]’ his last words to his wife, having been shot after ‘magisterially progressing down a street in Sarajevo’. In fact the car had been backing up after a wrong turn. When usually one gets no for an answer, FitzSimons gives us ‘No. No. No. No. No.NO!’ An unhappily favoured adjective appears often and to ill effect: ‘Smithy’ at war ‘became a veritable angel of death’. His adventures provoke ‘a veritable bushfire of coverage’. His craft is ‘a veritable glowing ghost plane crackling its way through the heavens’.

In a book so long there is surprisingly little social history (padding with flying anecdotes apart). There is a single comparison with the other Australian hero of the age, Don Bradman (who does not make the index). The uses that newspapers had for aviators’ exploits and the latter’s need of them are touched on too briefly. Politics and economics (except for the costs of fitting out flights) are hardly mentioned at all. One might also tease out an alternative view of Kingsford Smith as careless of others, ruthless, reckless, self-adoring, but that is not how FitzSimons wants his magnificent man. After the adulation that he heaps on him, one can only hope for a subsequent cooler appraisal of Kingsford Smith. Of course, the same goes for Bradman.

Comments powered by CComment