- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

There seems to be an ever-growing – I almost wrote market, but think I mean obsession – these days for the family history, the personal memoir, the parading of how I spent my childhood/adolescence/ protest years/personal and economic growth decades, before-finally-contributing-to-the-joy-of-past-and-future-generations-by-listing-my-achievements. Many of these are self-published. Kristin Williamson’s biography of her playwright husband is not, but perhaps should have been.

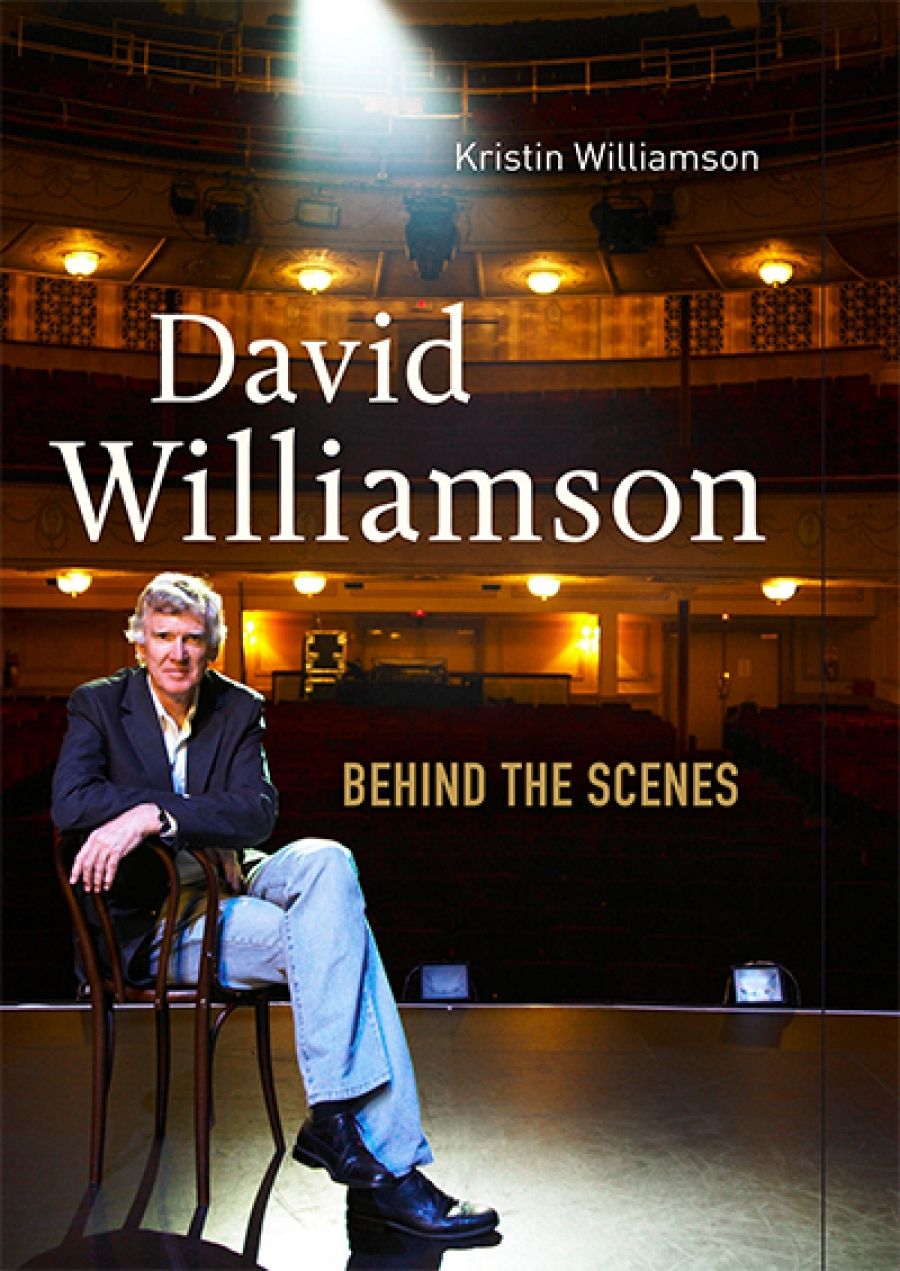

- Book 1 Title: David Williamson

- Book 1 Subtitle: Behind the scenes

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $49.95 hb, 560 pp

Alas, Kristin Williamson seems to have taken to heart the well-meant advice of that renowned cultural commentator and critic, Fred Dagg (aka John Clarke) who, several years ago, provided an admirable template for all would-be autobiographers (the present study is billed as a biography, but there is more than enough of the author’s own doings and views for the comments to apply):

This is a highly recommended form of leisure activity, as it takes up large chunks of time and if you’re a slow writer or you think particularly highly of yourself, you can probably whistle away a year or two … It’s not a difficult business and remember this is also your big opportunity to explain what a wonderful person you are and how you’ve been consistently misunderstood …

Any observer of the Australian theatre scene has known for years of David Williamson’s notorious thin skin when it comes to criticism. This book is studded with instances of the couple’s overreactions, and their tiresome obsession with putting any less than enthusiastic acolytes back in their box. As early as page fifty-two, we have Williamson bewailing the fact that ‘You had to be pretty tough to withstand the ridicule of those Tulane Drama Review-reading wankers in Carlton’. On page 154 he’s still complaining about criticism from Vincent Buckley and Dinny O’Hearn (‘Your words don’t sing’, a comment which alas still applies to some of Williamson’s dialogue). Five pages later, after the London production of Don’s Party, he complains that ‘The Australian Press in their typical paranoid fashion [surely a case of de te fabula?] reported only B.A.Young, Kretzmer and Barber [who had penned critical reviews]’. It would be nice to think that, after decades of success and with his position in the history of Australian theatre widely acknowledged, Williamson might follow the advice of Steven Berkoff (not given to moderate reactions towards critics) who recently suggested: ‘You’ve got to be grown up: take the bad with the good. You can’t be too uppity. And neither should you become like a narcissistic wimp that attacks critics.’

Just as disconcerting as the playwright’s sensitivity, however, are the author’s regular and enthusiastic attempts to redress the critical balance. A Handful of Friends, the first Williamson play I ever saw, in the 1970s, which left me quite bemused as to why he had the reputation he did in Australia, prompts the observation that ‘[it] reminded me of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, but seemed tougher because some of the characters were recognizable’. Apropos a workshop presentation of the play A Conversation at Vassar College in 2001, the author declares that the production was powerful (without giving any sense of how or why) but devotes more space to noting that ‘David had cleverly incorporated [the actors’] suggestions and even their humour into the script … but there were no gasps at the brilliant re-writes he’d stayed up till the early hours to create’.

This need for constant recognition is a tiresomely repeated note throughout the book. At the age of three, the playwright informs a doctor’s waiting room (and the reader), ‘I was born to be funny’. A few pages later we learn that he liked applause, ‘and … as a clever and gregarious little boy he grew up expecting it’. An autobiographical figure in a piece of fiction ‘can’t bear to be thought unexceptional’. You don’t need to be a pop psychologist to find an explanation here for Williamson’s feeling that, as W.S. Gilbert put it, he has never quite received ‘the deference due to a man of pedigree’.

Given the repeated assertions in the book that the playwright’s life feeds into his theatre, one might have expected that the author would have something uniquely interesting to say about the connection and how Williamson’s theatre compares to the dramaturgy of his contemporaries. No such luck. The level of critical insight is simplistic, the style by turns plodding or piffling, clamorous or commonplace. Hosts are charming, hamlets have pristine beauty, days are halcyon, food is unusually good, countries are culturally intriguing, critics are wretched mean-spirited moral zealots, a politician’s rapier wit flies fast and furious, people indulge in playful banter, Cuba is genuinely egalitarian (well, yes, but what about the gays and the dissenters?). It would be wrong to say the clichés come thick and fast: they roll relentlessly over the reader like the courses in the seemingly endless dinner parties that pad out the pages.

When this listing of trivia goes hand in hand with assertions such as ‘the stage … tends to be character driven, while film is plot driven’, or ‘The Department was also Chekhovian in that it had subtle moods’, one wonders precisely what the editors at Penguin were doing allowing such banalities to pass muster. But what can one expect when, according to the press, Ms Williamson’s editor can praise ‘the book’s fantastic texture … for which it takes real honesty’, and when its author can inform readers that her husband has now written more plays than Shakespeare? (Note: so have Alan Ayckbourn, around fifty at last count, and Jean Anouilh, more than seventy: neither, to my knowledge, put up their numbers against his to legitimise their theatrical CV.)

But why should one be surprised at this game of reducing theatre to a score-sheet, when the subject of this biography can assert, presumably in all seriousness, that ‘the arts are about fashion’? If this is David Willamson’s guiding principle, it goes some way toward explaining much about his choice of subject matter over the years and about his cultivation of his audience.

After ploughing through this unilluminating survey of the life and career of a major figure in Australian theatre, what really worries me is the possibility that, after Pamela Stephenson’s thoughts on Billy Connolly (2003), we may be about to be overwhelmed with a flood of spousal biographies (not something that readers of Ibsen, O’Neill, Brecht or Beckett had to worry about). I can already see looming on the horizon a fat volume based on Kathy Lette’s life with the orotund Geoffrey, or Norm’s insightful examination of Dame Edna’s artistic and social achievements (though, come to think of it …).

Comments powered by CComment