- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

In 1976 Carleton Gajdusek received the Nobel Prize for his scientific research into Kuru, a degenerative brain disease that afflicted a small population of Fore people in the Highlands of Papua New Guinea. This book is the story of the complexities of that scientific discovery as a social process. It is also the story of Gajdusek, a medical scientist whose intellectual energy and boundless egotism ensured that the fame and glory associated with this medical advance were his, unambiguously and singularly.

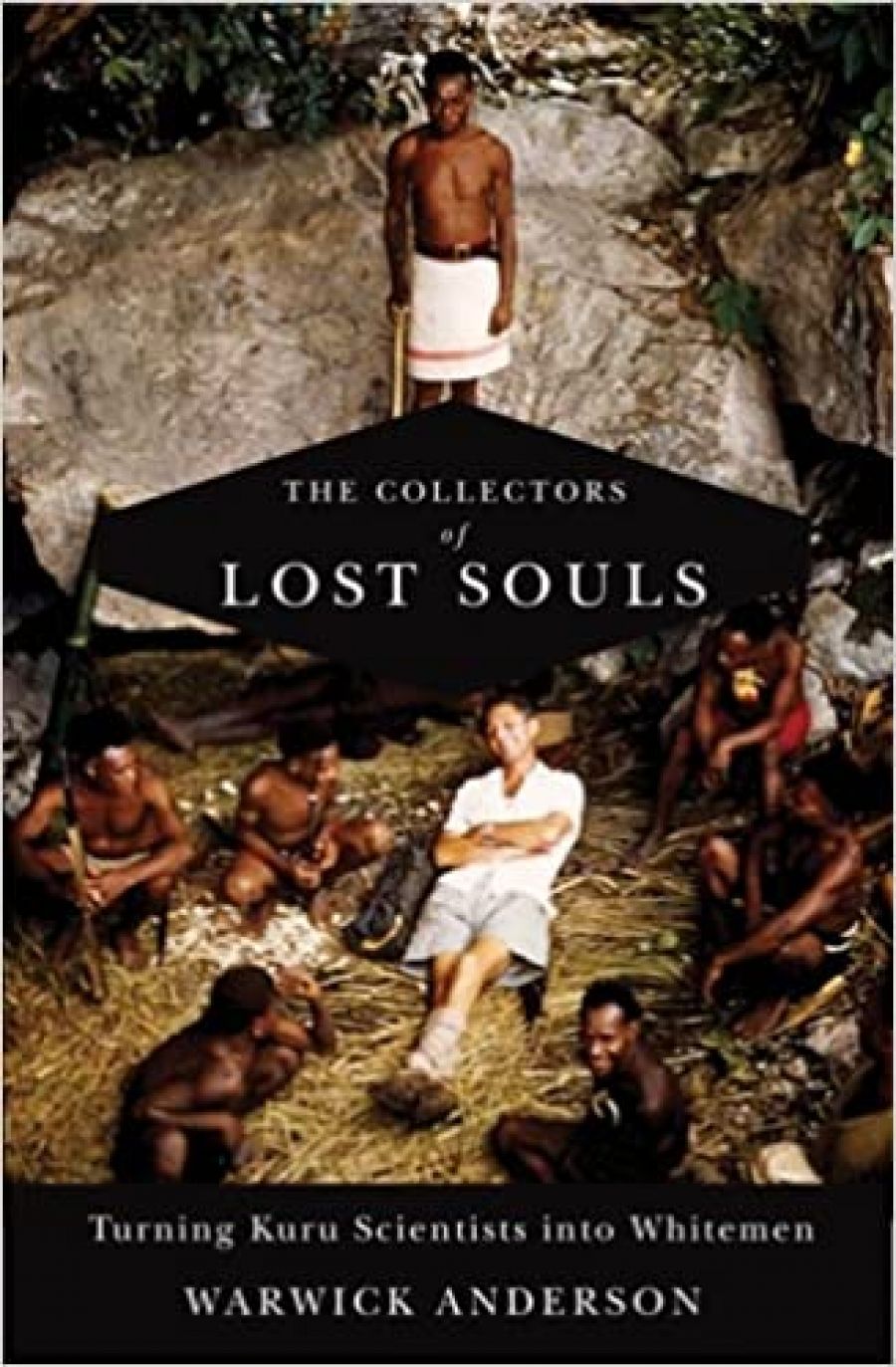

- Book 1 Title: The Collectors Of Lost Souls

- Book 1 Subtitle: Turning Kuru scientists into whitemen

- Book 1 Biblio: The John Hopkins University Press (Footprint Books), $49.95 hb, 318 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/zWDYO

Gajdusek took up a fellowship at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute late in 1954, but found Melbourne and the majority of his colleagues dull and bourgeois. On a visit to the Australian National University, he ‘deftly and irresistibly attached himself’ to Charles and Edie Valentine, anthropologists who were about to set off to do research in Papua New Guinea. He worked with them in East New Britain and then returned to Melbourne. But his interest was sparked, and in 1956 he received funding from the US National Institute of Health to embark on research in the Highlands region of Papua New Guinea. There he met Vin Zigas and encountered his first case of Kuru: a young Fore girl who was already seriously ill and displaying symptoms of advanced neurological disease. None of the tests identified the cause of her illness. Her family was convinced that she was a sorcery victim and would inevitably die, which she did after several months.

The Fore people had been the subject of anthropological research in the early 1950s, when Ronald and Catherine Berndt worked there. Ronald Berndt’s ethnography, Excess and Restraint: Social control among a New Guinea mountain people (1962) portrayed the men as aggressive, misogynistic and bellicose. He documented their mortuary cannibalism and their sadistic sexual violence in prurient detail, describing the prevailing social atmosphere in grim terms, with sorcery and the threat of vengeance permeating all relationships. Berndt presented sorcery in functionalist terms, arguing that it provided the constraints and checks on male aggression that ensured that an uneasy political equilibrium could be maintained. He studied various types of sorcery, including Kuru, but concluded that the symptoms described were consonant with hysteria and were a psychosomatic reaction to the dramatic social changes the Fore were experiencing.

Warwick Anderson suggests that an analysis of the networks of exchange in the region might have provided a better explanation for the social cohesion that bound Fore men together, creating relations of trust and obligation that overrode their tendencies to fight and kill one another. This emphasis on exchange relations has characterised anthropological inquiry into Melanesian sociality for several decades. Anderson’s use of its terminology and tropes moves it into new territory, as a way of interpreting the dealings between Western medical scientists and Fore families whose relatives contracted Kuru.

Gajdusek’s relationships with Fore people were, like his relations with his scientific colleagues and friends in America and Australia, based on his own narcissism and needs. He had always preferred the company of children and adolescent boys; in Papua New Guinea he was able to ensure that he was constantly in their company. He trained a group of youths as ‘dokta bois’ (medical assistants). They travelled from village to village with him. He revelled in their energy and zest for life; he, in turn, delighted and entertained them. He professed himself ‘enchanted’ by the Fore people generally and by some of the boys in particular. In his early twenties, he had expressed the wish to be Peter Pan ‘and live always in Never-Never Land’; the Eastern Highlands seemingly provided him with this opportunity.

Anderson’s research included interviews with medical colleagues and others who had worked with him. The image of Carleton Gajdusek that emerges is contradictory. He captivated some and alienated others. All were in awe of his intellect and his energy, even Macfarlane Burnet, who was critical of his lack of collegiality and suspicious of his obsessive pursuit of scientific glory. Gajdusek evoked loyalty from some people who worked for him, but there is little evidence of his capacity to form close friendships with adults, even with those who admired him. While Anderson explores his diverse relationships, both professional and personal, the overwhelming impression he conveys is of a person of prodigious intelligence and imagination who remains emotionally infantile and unable to develop relations of mutual trust and respect throughout his life. Vin Zigas, the young doctor who first worked with him in Okapa in the Eastern Highlands, appears to be the only man with whom he established a relationship that was mature, but in terms of the research project into the causes of Kuru, it is clear that Gajdusek considered him his professional inferior. A substantial portion of the book is devoted to their constant pursuit of blood, tissue and brains from the recently deceased. The relentless desire for more scientific specimens meant that recently bereaved Fore people were harassed and cajoled, plied with gifts of food and other goods, in an attempt to relinquish body parts to the scientists. This macabre exchange of basic items of consumption (rice, sugar, tinned meat) for fragments of a person, and the hasty autopsies, with their ready similarities to the practice of cannibalistic butchery – the very practice that probably spread Kuru – cannot be glossed as transactions comparable to any in Melanesian custom. Even in those societies where human flesh was exchanged for valuables, the value of the flesh resided in its origin in a person and was never commensurable with commonplace goods. Gustatory cannibalism appears to have been extremely rare, and in many societies the ritual consumption of people killed in battle or of deceased relatives was an act of reverence or vengeance and surrounded by taboos.

It is in this context that Anderson’s use of anthropological theories of exchange, especially those transactions that have been interpreted as generating and engendering personhood and adult status, often seems contrived and inapposite. There are analogies, which he exploits, notably the ways that successful exchanges enable people to gain status and prestige, but throughout I was made uneasy by the lack of moral equivalence between the Fore participants and the scientists. Moreover, there is a special irony in the fact that the demise of Kuru is attributable to the cessation of mortuary cannibalism – as a practice that was prohibited by the Australian administration and discouraged by the missionaries – and not because the scientific research led to any cure. Indeed, Anderson’s own recent fieldwork interviews suggest that Fore people’s relinquishment of brains and tissue was done in hope that the doctors would find a successful treatment. What they also hoped for was the establishment of long-term relationships with white men that would facilitate their incorporation into the rich economy of their world. Their hopes were dashed there too, and now the Fore, in true Melanesian fashion, seek compensation for these failed, unequal exchanges.

There is a substantial literature on scientific discovery as a social phenomenon and the ways that colonialism provided new fields for research. The strange alliances between administrators, patrol officers, missionaries and anthropologists, each with their projects for knowing, subduing and managing their subjects, have been observed by numerous historians and anthropologists. Anderson’s contribution to this body of work is scholarly and ground-breaking. He combines the analysis of the trajectory of ‘discovery’ with the complicated web of personal relationships and political struggles in ways that simultaneously expose the myths of scientific ‘method’, of medical research as an intrinsically humanitarian endeavour and of the colonial enterprise as unitary. The person of Gajdusek – ‘the scientist as hero’, the romantic adventurer, the avid collector of ‘specimens’ and the zealous, persistent investigator of a scientific problem – embodies the range of forces at work in winning his Nobel Prize. It also allows us to contemplate the ways that scientists were able to distance themselves from the sordid and demeaning political relations between whites and ‘natives’, while availing themselves of the opportunities they afforded for unimpeded research. Gajdusek (long an exile in Tromso, Norway, dying there in December 2008) belonged to an era where he could style himself as a researcher in childhood development or viral diseases and opportunistically pursue his inquiries without questions being asked about his expertise, his ethical practices or his obligations to the subjects of his research.

Comments powered by CComment