- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The Book of Human Skin details the trials and tribulations of an innocent Venetian noblewoman named Marcella Fasan, a girl ‘so sinned agin tis like Job in a dress’, Gianni delle Boccole, loyal family servant and bad speller, explains. Marcella’s principal antagonist is her older brother Minguillo, who, out of filial jealousy and a desire to be the sole heir to the family’s New World fortune in silver, makes her a prisoner, a cripple, a madwoman, and a nun. Think Jacobean tragedy meets Gothic novel, then add some – namely a crazy Peruvian nun called Sor Loreta, who, in between fasting and self-flagellation marathons, terrorises the saner sisters at the convent of Santa Catalina in Arequipa. It is these four characters – Gianni, Marcella, Minguillo, Sor Loreta, plus the kindly Doctor Santo Aldobrandini, a specialist in skin and its maladies – who, unbeknown to one another, take turns narrating this novel.

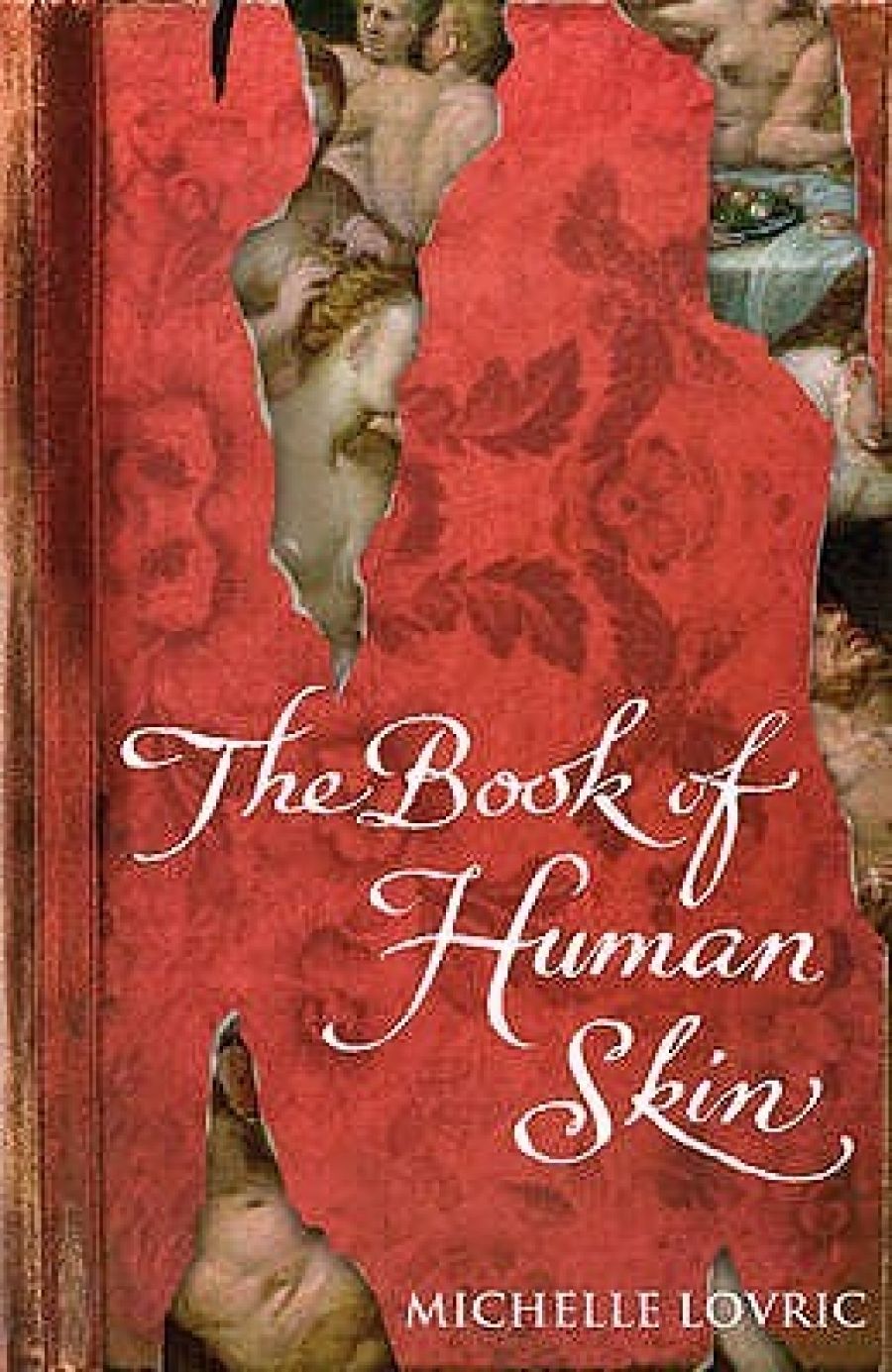

- Book 1 Title: The Book of Human Skin

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $32.99, 500 pp

The first half or so of The Book of Human Skin invites us to relish, as Minguillo does, ‘the unpleasantness of things’. We are told by Gianni, with Marcella and Santo the novel’s only reliable narrators, that Minguillo is ‘one o Nature’s erratas, one o God’s ferrule things’. He beats his mother’s belly black and blue in utero. A giant earthquake destroys ten cities in Peru the minute he is born. Butterflies drop dead when they fly over his cradle. Minguillo commits his first murder at four years of age (the victim is his older sister Riva, the method is poison mixed with ground-up glass). From here on, his atrocities become more and more macabre: kittens are killed with rusty nails, chickens are beheaded in a mock-up of the Reign of Terror’s guillotine, pins are inserted in the family bread and Marcella’s knee is blown to bits in a William Tell-like game of shooting between her petticoats. Meanwhile, in Arequipa, Sor Loreta ramps up her scourging, emulating the more grisly behaviour of medieval female saints. She turns boiling water, chains, pins, whips and pepper and lye upon herself in the pursuit of heavenly ecstasy, but also, her priora suspects, because she covets earthly fame. Sadomasochism, in this novel, isn’t just the villain’s modus operandi or the road to mystical experience for the religious – it is also assumed to be the central source of readerly pleasure.

Clearly, Michelle Lovric wants Minguillo to win us over à la Richard III. We are supposed to find his breezy brutality and his direct address (‘many warm hellos to Him again!’) shocking but seductive. But Minguillo is less ingratiating than grating. He is not witty enough to wheedle, and his brand of evil is too affected to be that combination of fun and creepy. The overcomplicated mechanisms Minguillo puts in place to maim and besmirch Marcella exceed Bond villain stupidity, despite the fact that he proved himself capable of sororicide as a child. Minguillo gleans his ideas for torture from the Marquis de Sade; he abuses countless whores because he thinks it goes with the territory, and he collects books bound in human skin for no other reason than to ensure that there’s always a prop at hand to stroke malevolently for the next wholly contrived wicked thought. But the most undermining thing about Minguillo’s evil is that it is overdetermined. Behind the bad behaviour lies ‘a mean portion of mother-love’ and the corrupting influence of the city of Venice itself. As Minguillo says, ‘We had got used to being ashamed of ourselves. Sitting in a warm bath of our own filth, we ceased to smell our disgrace.’

Minguillo’s evil is of the moustache-twirling variety, but Sor Loreta is another story. She is the novel’s more inspired villain because her self-delusion is complete. Sor Loreta is scary in the way violent fanatics really are: she is unafraid to turn that violence upon herself. Her asceticism is vainglorious; she is as vigilant in making sure that she is the skinniest woman in the convent as is the next catwalk model, and she regards other nuns’ blindness to her stigmata, halo, and angels as evidence of their lack of enlightenment. Meanwhile, she licks her lips at the sight of the Holy Eucharist and drinks the pus of sick sisters in the infirmary. In a novel that doesn’t understand the meaning of the word ‘subtle’, the most unsettling detail is the trail of blood that drips from the furtive cilice wrapped around her thigh. The Book of Human Skin’s tedious beginnings with Minguillo become compelling when Sor Loreta becomes the novel’s epicentre of evil.

Since Carnevale (2001), Lovric’s fiction has taken its inspiration from Venice. The Book of Human Skin is at its best when it departs this over-mined literary location. Of particular note are the scenes of crossing the bitterly cold Andes and of everyday life at the convent of Santa Catalina, which are vivid in colour, atmosphere and general liveliness. For some, the attraction of reading historical fiction is that the pill of fact is gilded. Readers wanting this brand of kindly education will not find it in this novel, despite the thirty-three pages of historical facts and bibliographical information that follows the novel itself. We hear of the heinous execution of Túpac Amaru II, the Great Earthquake of Arequipa in 1784, and Napoleon’s rampage across Europe, but these events are simply cataclysmic backdrops to the private terrors of the novel’s characters. Lovric, in interview, has stated that ‘proper writing should have a perfume, not the dust of the library’.

I don’t usually read books like this. My tastes run to the more austere. If you settle in for a night’s reading at a straight back chair and a lead pencil at the ready, The Book of Human Skin will challenge your every readerly urge. But as Minguillo notes early on in the novel, ‘There’s no pleasing everyone.’

Comments powered by CComment