- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: 'Courage in your own'

- Article Subtitle: Maintaining the rage over the Balibo Five

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

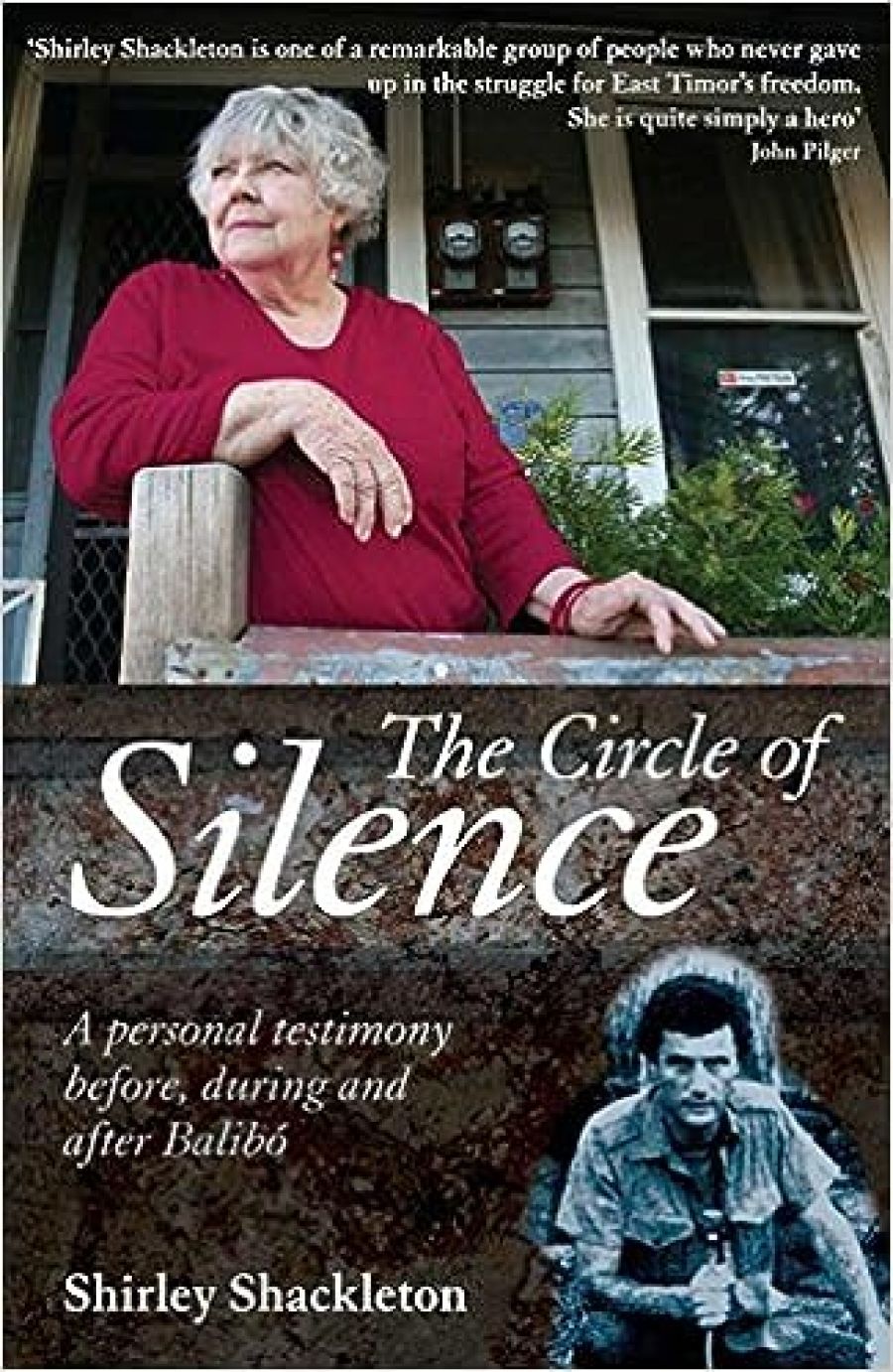

Shirley Shackleton is well known to those acquainted with the story of the fight for justice by the families of the Balibo Five, the five reporters who were slaughtered in 1975 in a border town of what was then Portuguese Timor. Her husband, Greg Shackleton, and his colleagues, Gary Cunningham, Tony Stewart, Brian Peters and Malcolm Rennie – all in their twenties – were killed by Indonesian soldiers at dawn on 16 October, shortly after filming a major infantry, naval and air attack on the town of Balibo.

- Book 1 Title: The Circle of Silence

- Book 1 Subtitle: A Personal Testimony Before, During and After Balibo

- Book 1 Biblio: Pier 9, $34.95 pb, 392 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

The Whitlam government compounded its sins by covering up the circumstances of the journalists’ deaths. This aroused considerable public anger and divided Cabinet in the days leading up to the Dismissal of 11 November 1975.

In following years the issue tended to fade, but Shirley Shackleton was among those who kept it in the public eye with her resolute campaign to uncover the truth about her husband’s death. Her determination to publish her own story was part of this struggle; she approached publisher after publisher without success. Now in her seventies, she hopes that The Circle of Silence, her first book, will be followed by others.

The author prefaces her book with an extract from Adam Lindsay Gordon:

Life is mostly froth and bubble,

Two things stand like stone,

Kindness in another’s trouble,

Courage in your own

Few people have doubted her personal courage. Her grit was demonstrated in 1989 when she visited Indonesian-occupied Timor in order to investigate the circumstances of Greg Shackleton’s death. Senior military brass, including defence commander Benny Murdani, who planned the attack in which the Five were killed, were gathering in Dili in a vainglorious mood; they had persuaded Pope John Paul II to visit, an event which they saw as endorsing the occupation. Shirley Shackleton decided to confront Murdani in the dining room of the Hotel Turismo, the 1960s Portuguese hotel favoured by travellers, journalists and secret policemen. I had shared a meal with the Five there shortly before they left for the border. A fortnight later, it was the setting for my interview (conducted with ABC reporter Tony Maniaty) with Guido dos Santos, the first eyewitness to describe their deaths.

According to the author’s own account, the hard man of the Indonesian campaign equivocated when she asked him how her husband had died at Balibo. She pressed him on the subject:

I spoke slowly, describing how badly his troops behaved towards their own people and how unnecessarily cruel they were to the Timorese. I asked if he knew how many young men being tortured had Indonesian fathers who had raped their Timorese mothers. ‘When you allow your troops to commit atrocities you make sure that Timorese will never accept you and neither will these sons of rapists whose mothers care for the cuckoos in their nests.’

Later, she attended the papal mass with the late Paddy Keneally, a fellow activist and a World War II veteran of the Australian campaign in Portuguese Timor. Indonesian plans went awry as Timorese youths staged a brave demonstration in the pope’s presence. It heralded the beginning of a spreading urban revolt which backed the guerrilla army still fighting in the mountains. The author’s firsthand descriptions of scenes such as this one, which captures her colourful banter with Keneally, are the strong point of the work.

Shirley Shackleton’s bravery may be indubitable, but at times she lacks compassion towards others, particularly the other Balibo families. She treats Greg Shackleton’s mother (and her former friend), Olwyn ‘Shonny’ Dryden, harshly. Shonny never recovered from her only son’s death and committed suicide in 1982. The issue is clouded by the fact that Greg and Shirley’s marriage had ended three months before he went to Timor, a question which the author deals with sensibly. Greg had gone to live with his new partner, Madeleine Feller, a relationship that Shonny accepted after initial doubts, but which led to her estrangement from Shirley and her isolation from her grandson, Evan. Shirley Shackleton’s portrait of Shonny as a deranged person who had been rejected by Greg lacks credibility. I met Shonny with Feller in early 1976, when she was the only family member who was politically active over the deaths. Shonny was an unconventional person and clearly as grief-stricken as all the relatives were, but she was also lucid, highly intelligent and respected by activists at the Timor Information Service, where she worked as a volunteer. Because Greg named her as next-of-kin, his passport and notebooks had been returned to her, indicating that they had remained close.

The family of Gary Cunningham has objected to the author’s claim that his father wrote letters to the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT), ‘insulting his son’s intelligence and blaming him for his own murder’. They have found no documentary evidence for it. It is worrying, too, that the author claims credit for initiating the historic 2007 Glebe inquest, undeniably the work of Maureen Tolfree, the sister of Brian Peters.

It is Shirley Shackleton’s nature to upset people. This helped to keep the Balibo issue alive for years when it was off the public radar. Journalists could always rely on her for a strong quote. It was unfortunate that they ignored the other four families, who were also campaigning in their own ways for the truth to be revealed.

In 2003 the Victorian government acquired the house in Balibo where the journalists had sheltered before their deaths. Premier Steve Bracks and Timorese president Xanana Gusmão inaugurated it as a memorial community centre for the Balibo population. The families were flown in for a service which was the nearest to a funeral ceremony they ever had, given that their loved ones were buried in Jakarta in 1975, without their informed consent.

Earlier, family differences had been inevitable, given the trauma relatives suffered, mourning in isolation as they did, and treated with contempt by the DFAT mandarins. This history was put aside on this sorrowful occasion, and attitudes have continued to mellow since. It would be unfortunate if The Circle of Silence reopens old wounds.

Various Timorese eyewitnesses to the killings came forward after Guido dos Santos testified in 1975. By 1999 there were around seven credible witnesses, most of whom appeared at the 2007 Peters inquest. They identified retired general Yunus Yosfiah, then a captain in Indonesian special forces, as having led the Balibo killings, with henchman Christoforous da Silva. The court found that there was sufficient evidence to indict the pair on war crimes charges under the Geneva Conventions, and handed the case to the federal attorney-general to pursue. Further investigations are well advanced, raising the hope that a measure of justice is possible. Shirley Shackleton can justly claim much credit for this success.

Comments powered by CComment