- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Exclusivist claims

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Living in Berlin during the rise of the Nazis, Christopher Isherwood wrote the stories that first brought him fame and later became the basis for the musical Cabaret. This was the period that Isherwood mined for his ground-breaking memoir, Christopher and His Kind (1976).

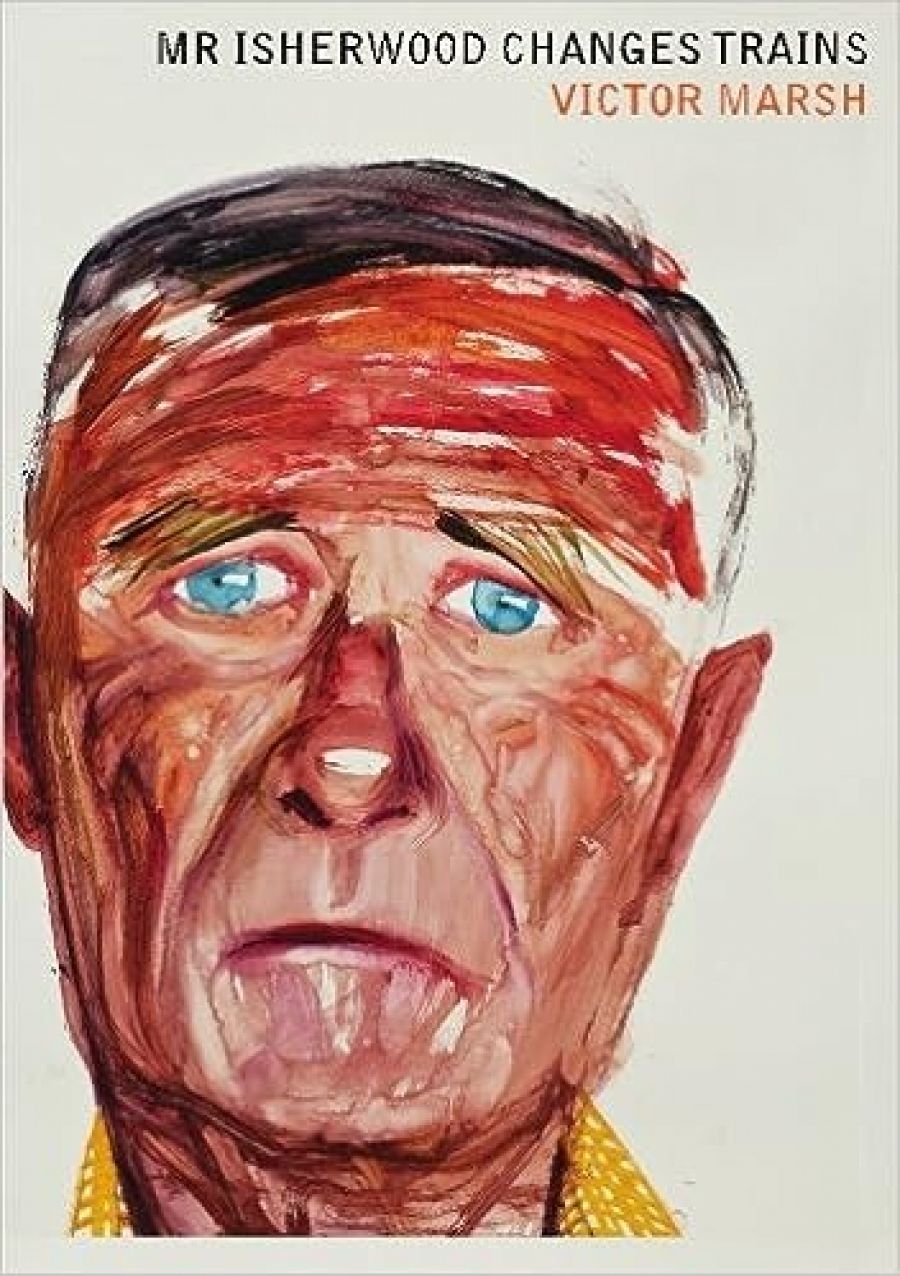

- Book 1 Title: Mr Isherwood Changes Trains

- Book 1 Subtitle: Christopher Isherwood and the Search for the 'Home Self'

- Book 1 Biblio: Clouds of Magellan, $29.95 pb, 310 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

It is this aspect of Isherwood’s life and work that is the subject of Victor Marsh’s Mr Isherwood Changes Trains: Christopher Isherwood and the Search for the ‘Home Self’. Marsh’s central preoccupation is with the question as to why Isherwood’s spirituality and religious writings have been dismissed or ignored by critics. The first reason, argues Marsh, is a ‘neo-colonial prejudice’ against Eastern religions; a predominantly British aversion, exemplified by W.H. Auden, who bemoaned his friend’s conversion to ‘heathen mumbo jumbo’. Marsh’s second, more compelling, argument is the presumption that gay men are, by definition, very much interested in sex and not at all interested in religion. Sex and spirituality, so this reasoning goes, are antithetical interests; one can commit to the body or the soul, but not both.

As Isherwood noted in his diary, his ‘personal approach to Vedanta was ... the approach of a homosexual looking for a religion which will accept him’. In it he found a tradition refreshingly unchristian in its attitudes towards sex. While Vedanta portrayed sex as a distraction from the goal of mystical union, it was not intrinsically evil and, significantly, sex between men was no more serious an obstacle than any other form of libidinous desire.

Marsh understands why queer folk (his preferred term) have abandoned religion with its ‘toxic, homophobic constructions’, but offers Isherwood as proof that there are kinds of spiritual practice in which they may find a home. Indeed, Marsh contends that the search for authentic selfhood, often prompted by the queer experience of marginalisation, is itself a form of spiritual enquiry.

This is an interesting subject. Unfortunately, the book is not. While Marsh is keen to distinguish his approach from the identity politics of the 1980s, Mr Isherwood Changes Trains feels painfully dated. Those who found themselves in a humanities tutorial during the last few decades will be wearily familiar with phrases dear to Marsh’s heart: the social and political construction of knowledge; postmodern interrogations of gender; the boundaries of culturally ordained subject positioning; unreconstructed moralistic and heteronormative assumptions, ad infinitum.

The result is a stylistic nightmare, while many of Marsh’s concerns are intellectually redundant. Take his announcement near the end of the book that ‘it is high time to ... apply this kind of criticism to the unquestioned exclusivist claims to knowledge authorised by the hegemonic constructions of meaning operated by religion’. If you take a deep breath and read slowly, it is possible to understand what Marsh is saying here, but surely religion’s period of ‘unquestioned exclusivist claims’ is long over. Similarly, Marsh’s intention to challenge ‘the figuration of the homosexual as either a religious pariah, or psychological misfit’ is the cry of a soldier arriving after the battle has ended. I am not pretending that the many varieties of human sexuality have found full equality, but statements like these ignore the enormous shifts in attitudes and rights created in part by men such as Isherwood.

Marsh sees conspiracy everywhere and is so eager to defend the honour of ‘this truly independent and original writer’ that he leaps in at the slightest provocation, upbraiding ‘blinkered views’ with the subtlety of a rubber mallet. This makes for unconvincing argument and exhausting reading. Marsh’s indignation at the critics comes to a head over a piece for Literature and Psychology, written by D.S. Savage in 1979. No doubt, Savage’s was a reductive psychoanalytic reading, but does Marsh really need to spend much of one chapter denouncing a thirty-year-old journal article?

If it is a flaw for a critic or biographer to have too little love, Marsh evinces too much. Despite Isherwood’s own cutting acknowledgment of what he referred to as ‘the darling ego me’, Marsh insists on his exemplariness. His sympathy for all Isherwood did and wrote is in stark contrast to Marsh’s caricature of other perspectives. Marsh rejects ‘the modernist view’ of the self ‘as a single solid entity set against an objective world’ (itself a bizarre claim: has he read Joyce, Woolf?), but only Christopher and his kind are granted the kind of vivid and protean subjectivity that Marsh extols. Every perceived ‘enemy’ is ploddingly homogeneous and static: ‘Britain refuses to relinquish its investment in empire’; ‘schoolmasters and family fully endorsed the official line’; Christianity is the source of ‘customary prejudices’ and ‘antique religious bigotry’.

Ironically, it is when discussing religion that Marsh’s prejudices are most evident. The book makes the clichéd distinction between religion and spirituality: put simply, the former is what your adversaries believe and do, while the latter describes your own authentic practice. No believer, not even Isherwood’s mother, dismissed for her ‘pious embrace of Anglicanism’, thinks they are engaging in dead ritual or moribund institutions. Spiritual enquiry is not the provenance of any singular tradition.

There is a strong personal sympathy between Marsh, ‘a postmodern, queer man’, and his subject, and Mr Isherwood Changes Trains has the air of emerging from a lifetime’s journey and, more latterly, from a doctorate. However, the validity of that journey does not in itself make for a good book. Perhaps I am betraying myself as one of the ‘myopic literary commentators, comfortably and even unconsciously ensconced within the cosy confines of the dominant meta-narratives’. Or perhaps I am right to expect better from our universities and publishing houses.

Comments powered by CComment