- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: No chance

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Some stories are very familiar to us, as a society, stories whose ugly truths we seem to have accepted, may even have, belatedly, apologised for, but the story of Joy Janaka Wiradjuri Williams, as told by Peter Read, reveals how much White Australia still has to learn about the complexity of our national past and the tragedy of its continuing legacy. Eileen Williams, three weeks after her birth in 1943, was sent to the United Aborigines Mission Home at Bomaderry, where she was renamed Joy. She grew up in state institutions and was later incarcerated in psychiatric hospitals, spending many years struggling with alcohol and drugs. As a young woman she had a baby taken from her, a repetition of the trauma inflicted on her mother and her grandmother. Joy, a poet and activist, mounted a long and unsuccessful lawsuit against the New South Wales state government. She died of cancer, alone, in 2006.

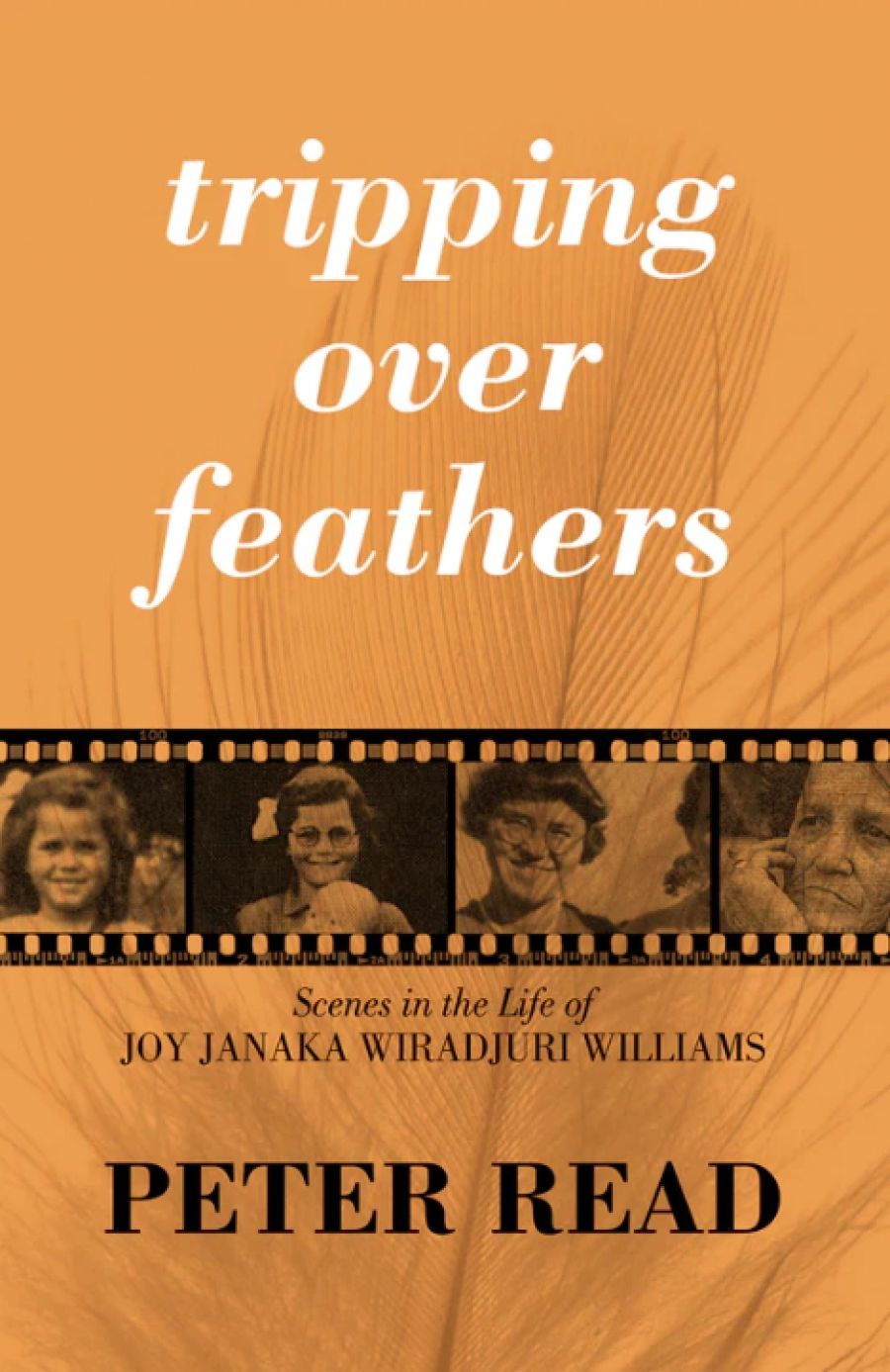

- Book 1 Title: Tripping Over Feathers

- Book 1 Subtitle: Scenes in the life of Joy Janaka Wiradjuri Williams

- Book 1 Biblio: UWA Publishing, $32.95 pb, 300 pp

Read’s use of direct speech is a riskier move. He argues that the dialogue is ‘historically informed’ through his own friendship with Joy and his thirty years as an historian of Aboriginal Australia (it is to Read that we owe the phrase ‘the Stolen Generations’). The introduction gives a helpful summary of the sources used for each chapter, but these do vary in reliability, ranging from personal recollections (including Read’s own) and official correspondence to photographs and the simple ‘imaginary’. This is perhaps a frank acknowledgment of what much biography, and a significant proportion of history, always is.

All biography involves some degree of ventriloquism, a vexed reality when the subject is a black woman animated by issues of voice and representation. But the figure of Joy Janaka Wiradjuri Williams emerges powerfully in these pages. This is partly because Read resists the easily sentimental. Tripping over Feathers does not offer the clear emotion of small children torn from wailing mothers. Confused as she was by medication and illness, Joy cannot say for certain whether her daughter Julie-Anne was forcibly taken or whether she consented to her adoption. Later, drink was the only currency that she and her mother could find to achieve closeness; just as sex was a substitute for affection. At each of the longed-for family reunions, hope is scuppered by disappointment and estrangement.

Read shows that Joy responded to the disastrous events of her life by developing a personality that ‘tended towards the abrupt, the calculatedly abrasive and sometimes the terrifying’, admitting that even as her friend and biographer he shared in the ‘fierce ambiguity’ of others who knew her.

Describing the treatment of children in traditional Aboriginal society in ‘Durmugam: A Nangiomeri’ (1959), W.E.H. Stanner wrote:

Aboriginal culture leaves a child virtually untrammelled for five or six years. In infancy, it lies in a smooth, well-rounded coolamon which is airy and unconstraining, and rocks if the child moves to any great extent. A cry brings immediate fondling ... Its dependence on and command of both parents is maximal, their indulgence extreme. To hit a young child is for them unthinkable.

This was not Joy’s experience. At thirteen she was told the ‘bad news’ that she was Aboriginal; her own daughter did not make the discovery until she was an adult and parent. When Joy finally located her mother at a Nowra hospital, Dora’s first act of greeting was to slap her in the face.

‘Never had a chance.’ This is Joy’s refrain to herself and, in one sense, the central thesis of Read’s book. But biography teaches us that our lives are always shaped, but never determined. As Brecht wrote, ‘Everything changes. You can make / A fresh start with your final breath. / But what has happened has happened. / And the water / You once poured into the wine cannot be / Drained off again.’ As individuals and as a nation we must acknowledge that ‘what has happened has happened’, and we need the courage and determination for that ‘fresh start’.

Comments powered by CComment