- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Nature Writing

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Divinely lovely

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

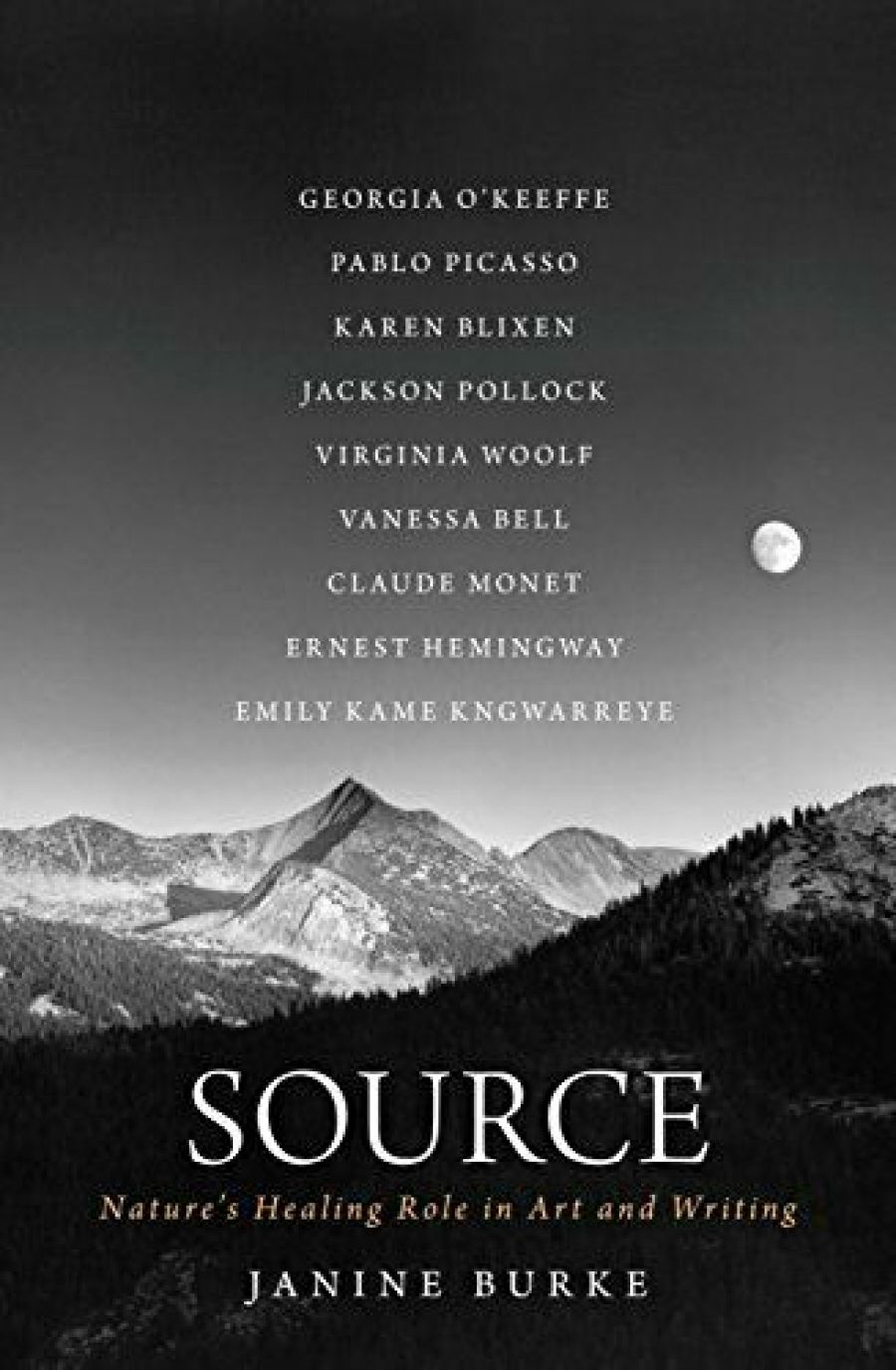

Don’t be put off by the subtitle. This is not a work driven by some New Age personification of Nature. If you’re looking for a gloss on the one-word title, you might focus instead on the inspired austerity of the cover photograph: Autumn Moon, the High Sierra from Glacier Point, by Ansel Adams. Then again, the book contains no mention of Ansel Adams, or of Glacier Point. During the course of the chapters, many inspiring and extraordinary places are visited, but this is not one of them.

- Book 1 Title: Source

- Book 1 Subtitle: Nature’s healing role in art and writing

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $65 hb, 432 pp

Each chapter tells the story of an artist’s or writer’s journey back to some lost childhood place, not necessarily as a literal return to where they grew up, but as a recovery of elemental forms of connection. The genius of these great modern innovators is a genius locus. They have in common a turning away from the metropolitan centres commonly associated with aesthetic breakthrough, and are driven by deeply sourced psychological compulsions to be where they belong. Once they achieve this return, their most potent work wells up, as if of its own accord. Woven into these narratives of reconnection are accounts of the personal relationships that were often bound up with the choice of place and the decision to go there.

This raises the question of how Burke’s subjects were chosen. She states unashamedly that the main principle of selection was her own love of and admiration for their work. Underlying that, though, are surely tendencies of fascination, and my sense is that she is, if anything, more engaged with stories of personal relationship than with the creative mystique of place that is her avowed subject. In the chapters on Monet, Picasso, and Woolf, I felt that the theme of genius loci was being pushed uphill a little, while the chapters were driven by an involvement with the interplay of personalities and sexualities.

In the cases of Pollock, Blixen, O’Keefe, Hemingway, and Kngwarreye, forms of animism are clearly their driving force. For me, these chapters have a better balance and cut to the chase in more convincing ways. ‘The grass was me, and the air, the distant invisible mountains were me,’ writes Karen Blixen; or, as Pollock more succinctly declares, ‘I am nature.’ Emily Kngwarreye wouldn’t have needed to make any such declaration: the ‘I’ in her cultural environment does not make itself an issue in that way. Hemingway turns the dynamic around, inflating the ego by pitting it against the scale of the ocean. ‘To govern the sea is a superhuman dream. It is both an inspired and a childlike will.’ In pursuit of this dream, the individual self is drowned in energies so massive that they cannot be contained in its boundaries.

Some of the best moments in this book are those given over to the words of the artists, in expressions of epiphany. Blixen recalls a dawn vision on safari, as a great herd of buffalo seemed to materialise from the morning mist, ‘as if the dark and massive, iron-like animals were not approaching, but were being created before my eyes and sent out as they were finished’. Pollock, sitting on the dunes, ‘can hear the life in the grass’. Burke also has epiphanies of her own. She writes in the third person about the experience of visiting Pollock’s studio at The Springs on Long Island, and walking across the paint-splattered floor in the special slippers provided to her. ‘Suddenly, she feels the energy rushing up … from the web of painted lines, so fast and intense it seems she is lifted off the ground.’

To return to the subtitle: healing is one of the themes running through the chapters. These artists and writers are variously reclusive, depressive, obsessive, touched by psychosis, suicidal. For many of them, natural connection is a passion of last resource, as human bonds fail them. This is darker terrain, but Burke doesn’t show signs of wanting to follow them into it. Her preference is for the evocation of air and light.

The sceptic in me was provoked by this, especially in the chapter on Virginia Woolf and her sister, Vanessa Bell. These two inhabited a distinctive literary and cultural milieu, as part of a circle of creative geniuses, including their husbands Leonard Woolf and Clive Bell, the painter Duncan Grant, the innovative curator Roger Fry and the writer David Garnett. Against the broken patterns of mental and emotional response in which Virginia became fatally caught, there is something troubling about the smooth style of talk cultivated in her circle. Nature is a personalised paradise. In Leonard’s account, their rural retreat of Asheham is a ‘lovely house and the rooms within it were lovely’; from the windows, the view across the valley was ‘romantic, gentle, melancholy, lovely’. Virginia finds it ‘so lovely’ to walk out on the Downs. Leonard becomes ‘a fanatical lover of the garden’. In Vanessa’s painting, there emerges ‘a divinely lovely landscape’. Given their overabundant talent with words, how could these people be so vacuous? One gets the sense that they were in denial about something. The natural world is not all light and air. It doesn’t always heal. It has darker energies, and a potent connection to it must engage with these. Burke doesn’t exactly shy away from the doubleness of natural influence, but nor does she seriously address it.

I wonder how much this is to do with marketing preferences for a ‘feel good’ book: the cover blurb refers to Edens and beloved childhood sanctuaries. In a book for the general reader, it is much harder to deal with the realities of a demon-driven psyche in which alcoholism and suicidal tendencies ultimately defeat creative energy. The crux comes in the last chapter, where Burke recounts her journey to Utopia, in the Central Desert. ‘I feel I’ve descended into one of the circles of hell,’ she admits. The works of Emily Kngwarreye reveal a utopia that coexists with the misery, and achieve a massive serenity that provides a redemptive story on which to finish, but I am not sure that this works as a story of healing. The word is too easy to latch on to, and it offers false closures.

Comments powered by CComment