- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Custom Article Title: Richard Harding reviews 'The Unforgiving Rope' by Simon Adams

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: 'If I English, I not be hung'

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Simon Adams’s thesis is that capital punishment was crucial in how the West was won: ‘The gallows were a potent symbol of an unforgiving social order that was determined to stamp its moral authority over one-third of the Australian continent.’ But hanging was discriminatory; it ‘was never applied fairly or impartially in Western Australia’. Adams points to the fact that ‘there were 17 men hanged between 1889 and 1904, all of whom were “foreigners”: two Afghans, six Chinese, one Malay, two Indians, one Greek, one Frenchman and four Manilamen’, but not a single ‘Britisher’. Capital punishment was racist, reflecting the ‘distortions and prejudices of the British colonial legal system’.

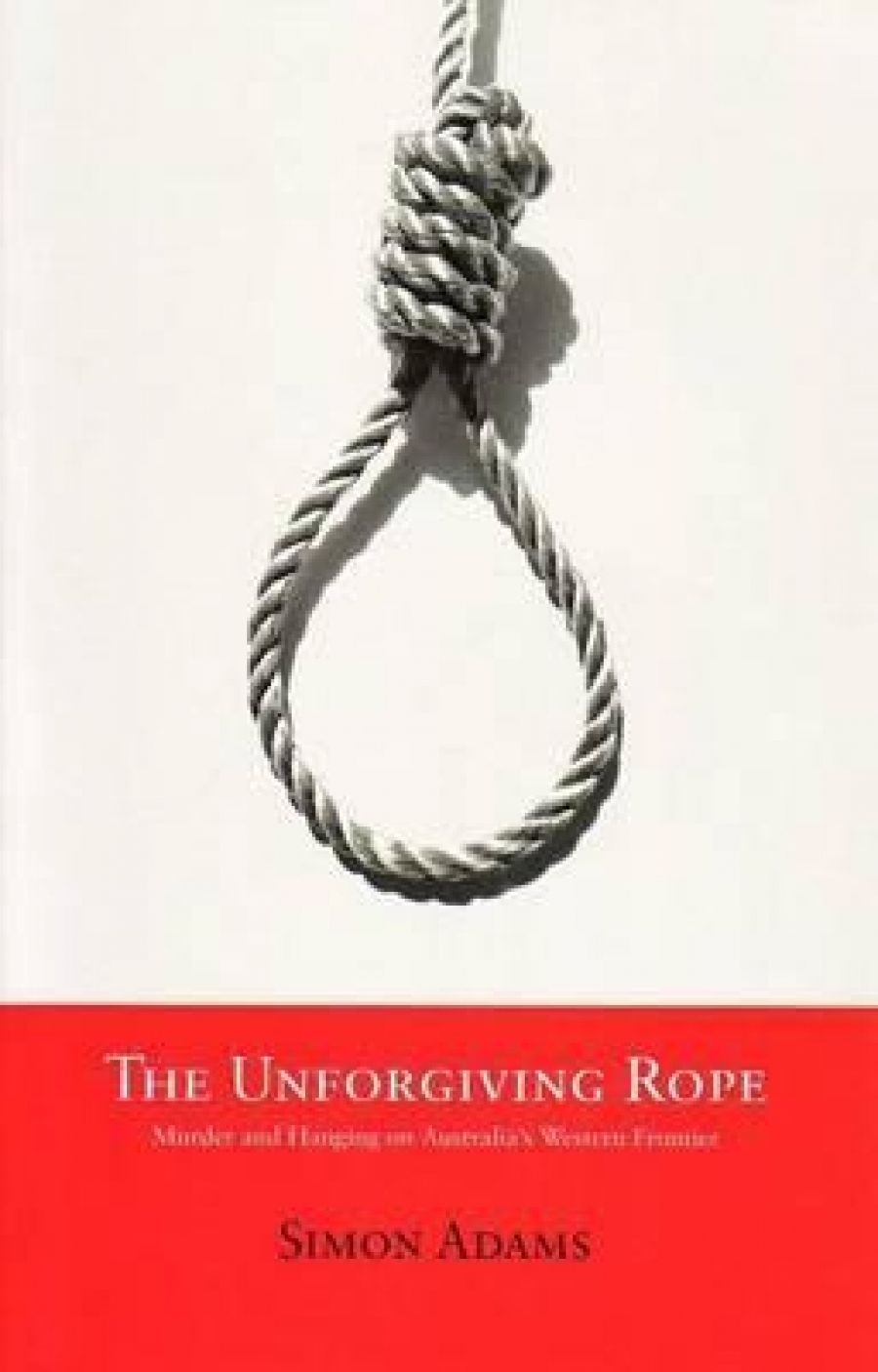

- Book 1 Title: The Unforgiving Rope

- Book 1 Subtitle: Murder and hanging on Australia's western frontier

- Book 1 Biblio: UWA Publishing, $32.95 pb, 310 pp

Adams certainly establishes his argument in relation to the Aboriginal population. In 2010, structural racism in the criminal justice system continues, minus the additional stain of capital punishment. With the other ethnic groups it is not quite as clear; there was racism in abundance and there were hangings of ‘foreigners’, but the cause–effect link is loose. However, Adams reveals some fascinating material – blood-curdling yarns and forensic analysis, interspersed with the social and political history of the times. For example, ‘Murder in a Coolgardie Mosque’ describes the shooting of Tagh Mahomet, the richest cameleer entrepreneur in the Eastern Goldfields, by Goulam Mahomet, a poor worker in the industry. From Goulam’s perspective, this was a pre-emptive strike against a man who had a contract out on his life. Adams weaves this in with the collapse of cameleering once the railway line had been extended to Coolgardie from Southern Cross, and with the consequent disappearance of Australia’s largest Afghan community.

A year before Tagh’s murder, a ‘Britisher’ had killed two Afghans after an argument at a water hole, which they were using for their ablutions before prayer. At trial he was acquitted. Goulam’s last words on the gallows high-lighted his discriminatory treatment:

I gave myself up. I believed there was justice in Englishmen; but now I not believe there is justice. I give my life into their hands, and they not do justice to me. I am innocent! Why, then, hang me? If I English, I not be hung. An Englishman shoot two Afghans, and he was let go. Thanks to God, I am not guilty before that one Judge, before whom I shall be soon.

This case would seem to support Adams’s thesis. However, in cases relating to Japanese and Chinese and Irish murderers, he does not fully establish that the systematic racism in the colonial culture accounted for the decision to execute some unpleasant characters.

As for Aboriginals, they constituted sixty-six per cent of the death sentences and thirty-nine per cent of the executions. These figures far exceeded the tiny indigenous population. The rate of commutations seems surprisingly high, but even mercy was racist. The murder of one Aborigine by another didn’t really matter that much. An 1865 editorial in one of the local papers differentiated between ‘a crime committed by a savage, in blind deference to barbarous custom, for mere purposes of expiation, and one committed by a person of superior race for revenge or passion’.

Executions were public events until 1870, after which they took place behind closed doors. However, an 1875 law permitted hangings of Aborigines still to be public. In 1892 three Aborigines were hanged in the East Kimberley, with sixty other Aboriginals being rounded up and compelled to watch.

Adams refers also to the various punitive expeditions by police and settlers. For example, in 1865 about twenty Aborigines were shot and killed in the West Kimberley in revenge for the killing of three white settlers. The number of non-judicial executions of Aborigines over this period substantially exceeded the number of authorised hangings.

The techniques of hanging were crude, often leading to decapitation or strangulation. Adams refers to the development of the ‘long drop’ technique at the newly constructed gallows in Fremantle Prison, in 1888. Citing the evidence that this produced a clinical breaking of the neck, The West Australian denounced the ‘contemptible and maudlin sentimentality’ of those who continued to oppose hanging.

Other stories will resonate with modern observers. Most notable is that of Martha Rendell, hanged for child murder in 1909. Adams seems to believe she was innocent. Like Lindy Chamberlain, the accused woman didn’t be-have in the expected manner: ‘Through all the sordid details of a gruesome and nerve-wracking trial the woman never quailed, but sat stolid and brazen,’ said The West Australian.

Eventually, capital punishment faded away in Australia, though Western Australia was the last state to abolish it formally. A turning point was World War I. Adams finds this ironic in a context where so much killing was happening in Europe. Actually, the two phenomena are directly related. A crucial issue for Australia was whether to allow its troops to be tried by British courts martial, and then shot, for supposed cowardice. It was irreconcilable with the evolving national identity to allow class-based prejudices to be imposed on free Australians. The Australian government interceded. That was the first significant turning point in the capital punishment debate in Australia, and though another fifty years passed before the last execution (Ronald Ryan in Victoria, in 1967) the political appetite for executions diminished from that time.

Comments powered by CComment