- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Film

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Seducing the audience

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Early in Gail Jones’s novel Black Mirror (2002), an Australian artist dives into the Seine to retrieve a bundle that may contain a drowning baby. Before rising to the surface, she experiences a kind of epiphany in the face of possible death – ‘a willed dissolution, a corrupt fantasy of effacement’. Later she revisits the experience in dreams, swimming through a surrealist underworld of discarded bric-a-brac: plainly, a metaphor for dreaming itself, as an act of plunging into mental depths and searching for hidden treasures.

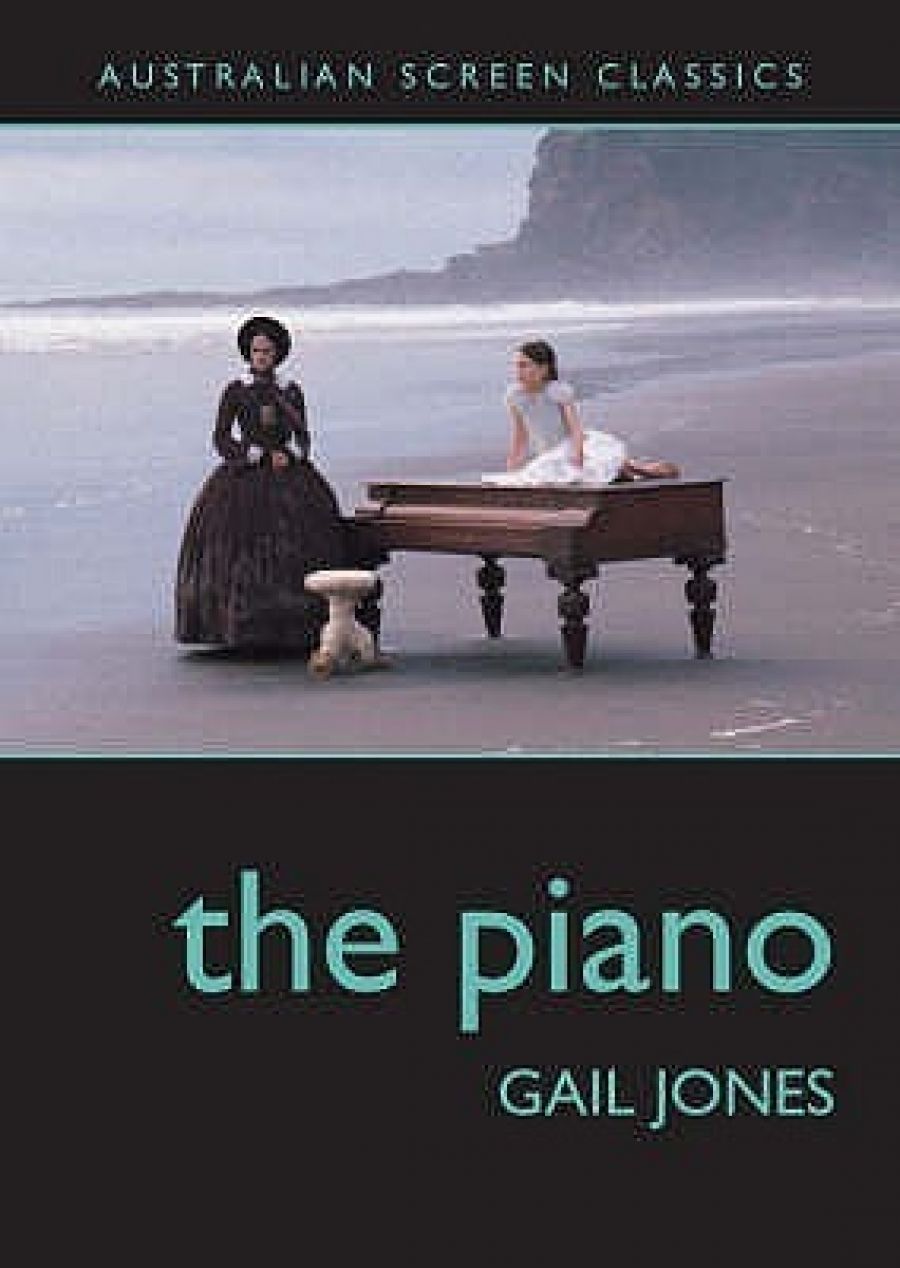

- Book 1 Title: The Piano

- Book 1 Biblio: Currency Press, $16.95 pb, 96 pp

It is easy to see why Jones was chosen to write this book, one of the strongest yet in the Australian Screen Classics series, and a showcase for Jones’s vivid and acute writing at its best. For all her creative vigour and critical intelligence, she can be frustratingly uneven as a writer of fiction: her clotted prose can seem at once too purple and too knowing, like a rush of sensuous apprehensions viewed in a theoretical mirror. As a critic, she is able to glide more easily between the abstract and the concrete. The Piano (1993), in many ways, is particularly well suited to the kind of extended critical treatment it gets here. Enigmatic without being entirely opaque, it holds back just enough of its meaning to open up space for a range of personal responses, a reticence figured, within the narrative, by the silence of its heroine Ada (Holly Hunter), who arrives in nineteenth-century New Zealand to be wedded to the unsympathetic Stewart (Sam Neill).

Since childhood, Ada has been defiantly mute – though she ‘speaks’ to the other characters and to the viewer through facial expressions, gestures, sign language, and, above all, by playing her piano (which, as Jones notes, is practically an extension of her body). Thus a critic writing on the film is faced with a peculiarly delicate task. As Jones says in another context, it is a question of ‘the paradoxical “wording” of silence’, of finding language to match Ada’s perceptions (and Campion’s) without denying their otherness.

Jones’s way of tackling this challenge involves approaching The Piano from a variety of different angles, proposing interpretations that tend to be more speculative than definitive. Chapter by chapter, she moves through the plot roughly from beginning to end, taking each episode as an occasion for a digression on a different theme: Campion’s use of tactile imagery, for example, or her take on the ‘colonial economy’ operating in the background of the main action.

Gradually, it becomes clear that much of the drama in the film stems from transactions between apparently opposed realms: male and female, European and Māori, land and ocean, adult and child. Likewise, Jones draws attention to a repertoire of images (hands, blades, veils, prosthetic devices) that recur in different contexts and link up in sometimes surprising ways.

Repeatedly, Jones compares the film’s way of assembling and dispersing possible meanings to a series of breaking waves. It is a metaphor that captures the flowing yet disjunctive quality of Campion’s style, with its highly charged images that often seem to rise above their narrative context before being cut off short.

Discussing the ‘slow escalation of physical contact’ between Ada and her suitor Baines (Harvey Keitel), Jones implies that the film itself practises a kind of seduction of its audience. So too does this book, which relies on evocative rhetoric as much as argument to make its case for The Piano as an artistic achievement.

In the interests of fairness, Jones makes clear that the film has come in for its share of criticism, quoting authors who suggest that the Māori characters are patronised as ‘happy-go-lucky natives’, or that Baines’s use of the piano as a bargaining tool in seduction amounts to rape. But without denying the possible validity of such charges, she seems to take them in her stride, as if they were part of the inevitable turbulence of a wave.

Comments powered by CComment