- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Primary colours

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Nicolette Stasko’s poetry is as far from the postmodern baroque as it is possible to be. This is not to say that her work lacks awareness of contemporary theories of art, but rather that her style eschews self-consciously clotted imagery, radical syntactical dislocation, and the production of high-sounding obscurities. There is nothing rebarbative here. At their best, the limpid surfaces of these poems invite the reader into aesthetic experiences where the pictorial is rendered with such clarity that the images resonate deeply. As we might expect from a poet who writes one of her best sequences in response to Cezanne and another following Van Gogh, the most satisfying of these poems recreate that moving stillness characteristic of figurative painting.

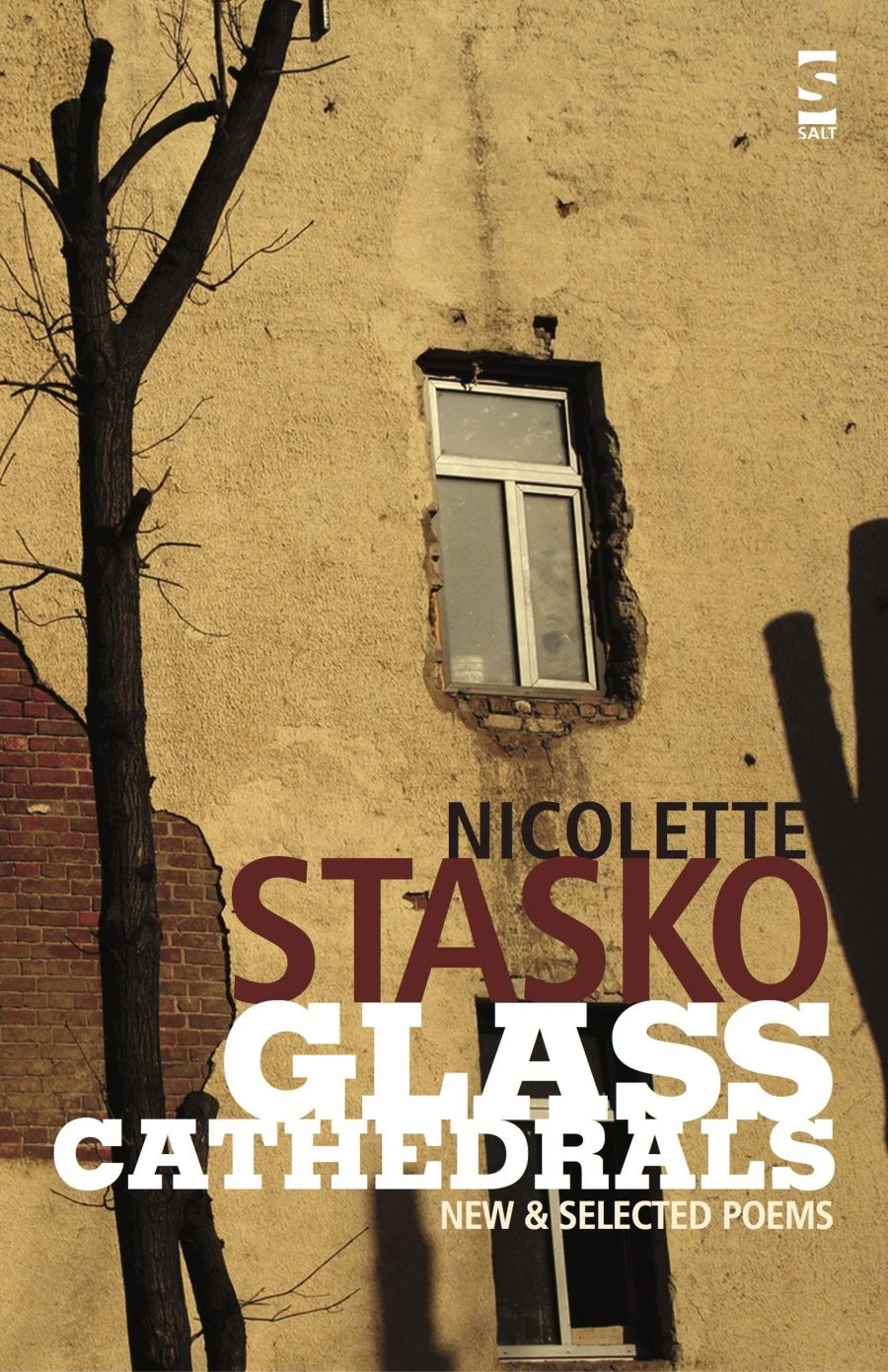

- Book 1 Title: Glass Cathedrals

- Book 1 Subtitle: New and selected poems

- Book 1 Biblio: Salt Publishing, $39.95 pb, 204 pp

In some of the poems, the dislocations articulated are not only geographical, but also emotional and intellectual. In ‘At Depot Beach’ or ‘First Lies’, for instance, the poet experiences joy through perceptions of her daughter, yet such emotion is hard won and we are rarely left unaware of the darker, more painful aspects of generation and regeneration:

I try to tell you – try

somehow to defeat

that sense of loss

we seem to inherit

with the colour of our eyes

and our mother’s old clothes

saying ‘the power

of creation’ not wanting

to speak of pain

the bloody sheets you always ask about …

Stasko has a painterly eye; light is important to her. Many of the poems shimmer with the brightness of primary colours (the poet is brave enough to repeatedly chance ‘red’, ‘yellow’, ‘blue’ and ‘green’), and the quotidian is often rendered with precision and delicacy. Yet the blackness of depression and the pain of lost love form the contrasting ground against which the poet pitches her words.

Some readers will protest that some of the line lengths are arbitrary and that the composition of single-word lines constitutes a technical cop-out – an extreme example of playing tennis with the net down. Others will miss a sense of the political world in these poems and will lament that the social tends to arise in a distanced and decorative aspect rather than from the point of view of an engaged participant.

It is true that Stasko’s writing is risky. The ease with which the poems may be read and the sometimes unremarkable language in which they are couched can lead to the impression of a lightness at odds with the ostensible seriousness of the subject matter, and the almost invariable placement of the poems in beautiful, not to say genteel, surroundings sometimes whispers of a species of art for art’s sake. But the majority of these poems yield pleasures which make the risks worthwhile. Stasko manages a balancing act whereby flatness, bathos, and preciosity are avoided and the achieved poem is greater than the sum of its parts. Art is dealt with here not as an abstract escape but as part of lived experience. The most admirable aspect of the poems is the way that Stasko recreates the illusion of a speaking voice that is at once recognisable yet mysterious, cool yet intimate.

Readers already familiar with Stasko’s poems may be disappointed with the relatively small quantity of new work. But some of the opalescent diary poems from the sequence ‘Tressant’ are as good as anything she has previously written, and are signals of more good things to come from Stasko’s pen.

Comments powered by CComment