- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

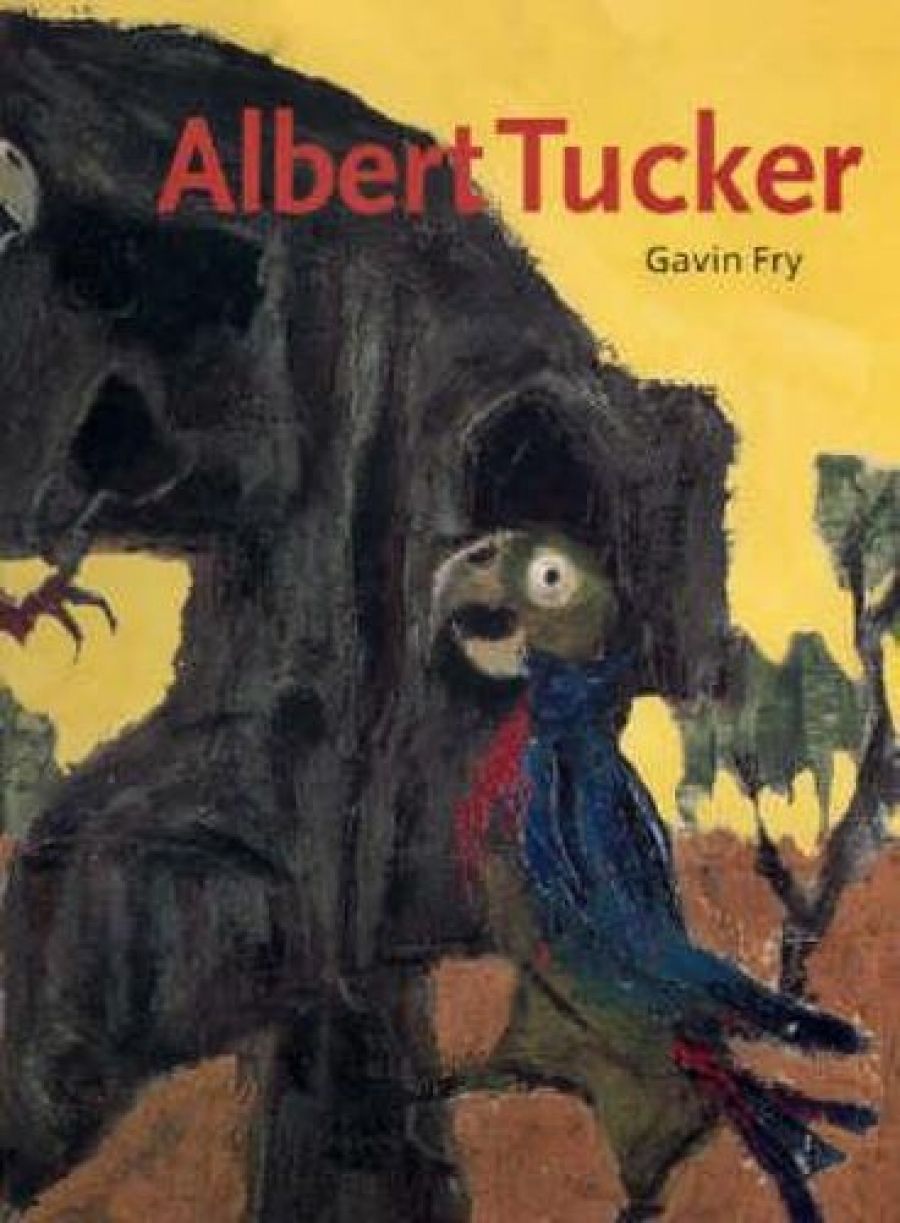

Handsomely illustrated, beautifully produced and authoritatively written, Gavin Fry’s monograph on Albert Tucker aims to establish him as an important artist within the Australian twentieth-century canon. Fry begins his introduction with the statement that Tucker ‘was a man who inspired strong feelings and his work likewise required the viewer to make a stand. Many found his work difficult, some even repellent, but the artist and his art demanded attention. Equally gifted as a painter, and possibly more so as a draughtsman than his contemporaries Nolan, Boyd and Perceval, Tucker belongs with this élite who revolutionised Australian painting in Melbourne in the 1940s.’ But is this really so? Was Tucker really so much better than his contemporaries, or even as good as them?

- Book 1 Title: ALBERT TUCKER

- Book 1 Biblio: Beagle Press, $120 hb, 252 pp, 0947349472

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/KoeYy

The arguments for some of Fry’s book may be assessed in relation to two exhibitions that coincide with its publication. There is a small show at the newly refurbished Heide, Melbourne’s museum of modern art: Meeting a Dream: Albert Tucker in Paris 1948–1952, an inaugural exhibition for the new Albert and Barbara Tucker Gallery. The gallery was bequeathed to Heide on condition that there will be a series of never-ending Tucker exhibitions, with works by Tucker seen in the context of other artists such as Sidney Nolan, and recreations of Tucker’s exhibitions, such as the one in Rome in 1954 with Nolan. Can Tucker take so much exposure, and can the curators present endlessly novel views of this artist? It will be a challenge. Another current exhibition in Melbourne captures a decade of Picasso’s life with Dora Maar, entitled Love and War, 1940 to 1950, and which examines Parisian painting in the period that precedes Tucker’s years in Paris. This exhibition could have been chosen to develop and challenge the arguments advanced in Fry’s monograph.

Fry claims that the melancholic darkness that pervades Tucker’s early works was taken from Yosl Bergner and Danila Vassilieff, two migrant artists, who opened Tucker’s eyes to a style of European expressionism. So far so good, except that Bergner’s novel invention of cityscapes, such as his painting House backs of Parkville (National Gallery of Victoria) was a radical and original vision of Australia which Tucker failed to equal. It might be argued that Nolan understood Bergner’s cityscapes better than Tucker did. Who before or since has captured the bliss of a Parkville back street like Bergner? In other ways, Bergner was capable of developing an enduring vision in such works as those about the indigenous poor in Fitzroy.

Fry claims that Tucker’s distorted heads are formed from Picasso’s approach to distortion, in such pictures as are at the NGV. But is it not more likely that Tucker’s images of modern evil may be considered merely an imaginative response to his wartime job of drawing injured heads? Picasso’s wit and passionate sexuality failed to enter Tucker’s vocabulary. Similarly, the claim that Dubuffet was an influence on Tucker, when the latter was in Paris in the 1950s, is disproved by the telling juxtaposition at Heide of a Dubuffet on loan from the NGV with Tucker’s rather densely hung, dark and, to quote Fry, ‘repellent’ surfaces. The presence of Dubuffet’s painting illustrates just how little Tucker understood his surfaces. Unlike Fry, I see little of Giorgio de Chirico in Tucker’s work, none of the fantasy and classicist surreal of the Italian’s imagery. However, the impact of British painting, the brutalist kitchen-sink style of John Bratby and also something of the portraiture of Graham Sutherland seems to have engaged Tucker at various points in his development. These are the sources with which Tucker is in dialogue, rather than the super-sophisticated sgraffito surfaces of Dubuffet. Tucker’s adaptation of expressionism, and his vision of the evil of St Kilda, are always explained as his reaction to World War II. Yet his own real experience of urban conflict only occurred in the late 1940s when he visited Japan and saw the aftermath of the war. Could St Kilda have been that terrifying in wartime?

Throughout the book, Fry makes frequent comparisons between Tucker and Nolan, such as, ‘Like Nolan, Tucker explored the myth of the bush’. This is a rather harmless assertion, but Fry also claims that Tucker triggered Nolan’s creation of the Ned Kelly series with his symbolic crescent head. In 1962 Robert Hughes noted, in an article on ‘Irrational Imagery’ in Art and Australia, that ‘Tucker’s red crescent shape, in the Night Images introduced the idea of an abstract symbol form to Australian art’. On reading Hughes, so Fry claims, Tucker remembered how Nolan had been ‘bowled over’ by a painting in his studio. Nolan asked if he could swap the work for one of his own, an offer Tucker declined. Tucker recalled that Nolan sat studying the picture and then left the studio. The first images of Ned Kelly appeared immediately afterwards. I find this rather difficult to believe, as Ned Kelly’s witty, irreverent head does not depend in any way visually on Tucker’s crescent-shaped imagery. Nolan’s first engagement with Ned Kelly is usually dated 1946–47, about the same time as the Images of Modern Evil. When I interviewed Tucker many years ago, he told me a similar story. Perhaps Tucker had sown the seed of the story in an interview with Hughes. For most writers, such as T.G. Rosenthal in his recent monograph on Nolan (2002), there are composite formative influences at work in Nolan’s development of this self-image as Kelly. How facile to explain Nolan’s series as being triggered by something so visually different. Can one believe Tucker on Tucker?

Throughout his life, Tucker was a fabulous photographer, especially when he travelled. He was capable of quite wonderful self-portraiture, and witty images of European travel, such as the shot of his caravan on the edge of the Seine in Paris, where he is said to have camped for some time. The photographs enliven the book and are a relief from much of the repetitive, even ugly, surfaces of the paintings. The author is strangely defensive about Tucker’s photography, which seems odd at a time when photography dominates the contemporary art scene. Tucker expressed the wish that he did not want to be remembered as ‘merely’ a photographer, but for this reviewer at least, Tucker was at his best as a photographer. As Fry argues, the Japan trip opened up photography as a medium for Tucker. In 1983 Tucker’s Japanese photographs were printed for the first time by the Australian War Memorial. Undeveloped and seemingly forgotten photographs are emerging all the time. Dora Maar’s erotically charged photographs of one of her first meetings with Picasso, never printed during her lifetime, open the Picasso show at the NGV. Negatives from Nolan’s tobacco box were used to great effect by Damian Smith in his essay on Nolan as a photographer in the 1950s, for the exhibition at the NGV in 2003: Sidney Nolan: Desert and Drought. What more may be revealed in this fashion? For Tucker, it has been a saving grace.

Comments powered by CComment