- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Philosophy

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Douglas Adams’s The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (1979) suggests that the Babel fish, which, when inserted into the ear, offers instant translations of any alien language, cannot have evolved by mere chance. Similarly, proponents of Intelligent Design (ID) argue that, as Robyn Williams summarises, ‘there are parts of the natural world so complex and engineered with such precision that only a very smart intelligence, not blundering selection, could account for them’.

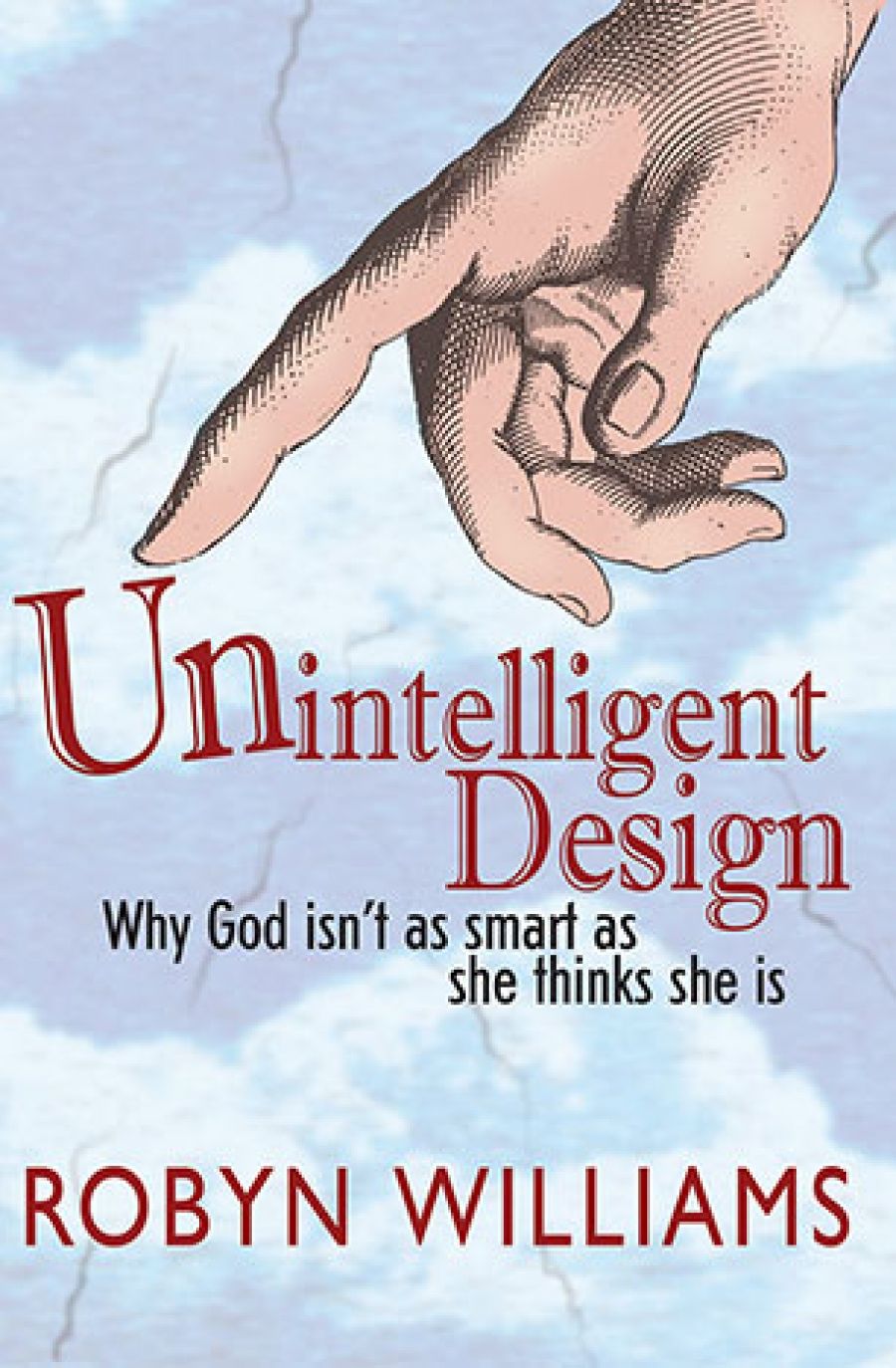

- Book 1 Title: Unintelligent Design

- Book 1 Subtitle: Why God isn’t as smart as she thinks she is

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $17.95 pb, 165 pp, 1741149231

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/56RNj

In response to ID’s aim to subvert the faith–reason dichotomy, Williams offers this incendiary summary: ‘ID is, in a way, terrorism focused on public education. The means are devious, the arguments deceitful and the consequences profound.’ Williams is particularly incensed by the fact that ID’s proponents pass off ID as science. ID emerged as a direct response to the United States Supreme Court’s ruling in 1987 that creationism, as religious belief, not scientific theory, could not be taught in schools. One critical purpose of ID, then, is that it should be a legitimate scientific challenge to the theory of evolution. But in 2005, Judge Jones, of the United States District Court, ruled against attempts to teach ID in a Year Nine biology class in Dover, Pennsylvania. The judge declined to offer an opinion on whether ID was right, but concluded that it was definitely not science.

At times, Unintelligent Design – half-primer, half-polemic – showcases Williams in fine form. Present in abundance is his ability to explain complex scientific theories to non-specialists without resorting to oversimplification. He achieves this with precision of language, liberal use of anecdote, an infectious delight in the natural world, and a personalisation of the development of scientific theories. Although overheated, he unleashes his caustic wit to reasonably good effect. Present, too, although awkwardly tacked on to the end, is Williams in more reflective mood, writing with depth about his own upbringing in a household in which communism was the religion of choice.

Ultimately, though, this disjointed book is a missed opportunity. The problem is partly organisational. It is not until Chapter 7 that the fundamentals of ID, and its crucial political and legal contexts, are adequately presented. Similarly, the chapter on ‘ID in Australia’ is cursory, and all the more disappointing because Williams offers insightful comments both on the different political and legal issues surrounding ID in Australia, and on the role and reputation of science: ‘It has been short of funds, depleted of students and worrying about pressures to increase its contacts with commercial interests. As a result, in its attempts to be noticed, Australian science has sometimes sounded strident or defensive.’ Williams states that Unintelligent Design is ‘more of a primer than a text, its aim to send you in search of the full opuses’, but he does not always properly identify the texts he discusses. And notwithstanding Robert T. Pennock’s point that critics of ID ‘typically find too much that is wrong with [ID] writings to cover in any given article’, a more detailed discussion of the theoretical underpinnings of ID would have been welcome. What’s there is rushed, its principal purpose seemingly to allow Williams and his readers to sneer.

I am not arguing that Williams should have been more generous towards ID. Despite the limitations of this book, his denunciation is persuasive, his fear well founded. Ultimately, though, the discursive partisanship of Unintelligent Design indicates that this is a debate about world views. Williams argues that science can show how but not why life exists; religion, he grudgingly accepts, might have a legitimate role in the ‘why’ debate. While he wittily debunks some of ID’s alleged science, he is less adept at reflecting on the implications of Barbara Forrest’s description of ID advocates: ‘[they] are not attempting to change the way science is currently done by introducing a better methodology or more viable hypotheses. … Rather, they are trying to change the way the public and influential policy-makers perceive science through their aggressive program of public relations activities.’ As Williams says, this strategy is known as ‘the wedge’. He correctly identifies an overt and precise PR campaign, evident most clearly in the manufacturing of a ‘controversy’ over evolutionary Darwinism and, more generally, a seemingly deliberate misrepresentation of the principles of scientific theorising. But if ID advocates are pursuing a multi-pronged agenda – theological, moral, social, political and economic, passed off as scientific – this suggests that the core issue is not about tactics but about principles. After all, why should creationists be barred from employing the marketing tools so influential throughout Western public policy?

In between atheism and creationism lies a huge grey area. The ID campaign in the United States is clearly underpinned by a neo-conservative agenda but that does not mean that anybody who cannot comprehend the ‘Big Bang’ theory or who flirts with ID is a Reaganite conspirator. The fact that ID has gained decent traction does reflect, as Williams insists, ‘proud ignorance’; but it also predicts the tone of debate we can expect to engage in if scientific advances continue to outstrip society’s ability to judge those outcomes.

Comments powered by CComment