- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

When the shiny new word ‘Surrealism’ was first minted, it was easy to find a shower of retrospective applications for it. The congested canvases of Hieronymus Bosch, for one, still spring to mind, though we need retrace our steps no further than that cauldron of economic and philosophical instability – the period between the two world wars – to pinpoint its official beginnings. In 1917, one year before a combat wound despatched him, Guillaume Apollinaire used the term to describe the ‘unleashing of zany creativity’ in the ballet Parade.

There were many players. Some were unsuspecting recruits; others signed up with alacrity. One of the former was Sigmund Freud, whose exploration of the subconscious mind and how it underwrote the inclinations of humanity at large gave a boost to those painters whose strange conjunctions of imagery had been prompted by free association and a dragging of the subconscious seabed to snare the detritus of dreams and nightmares.

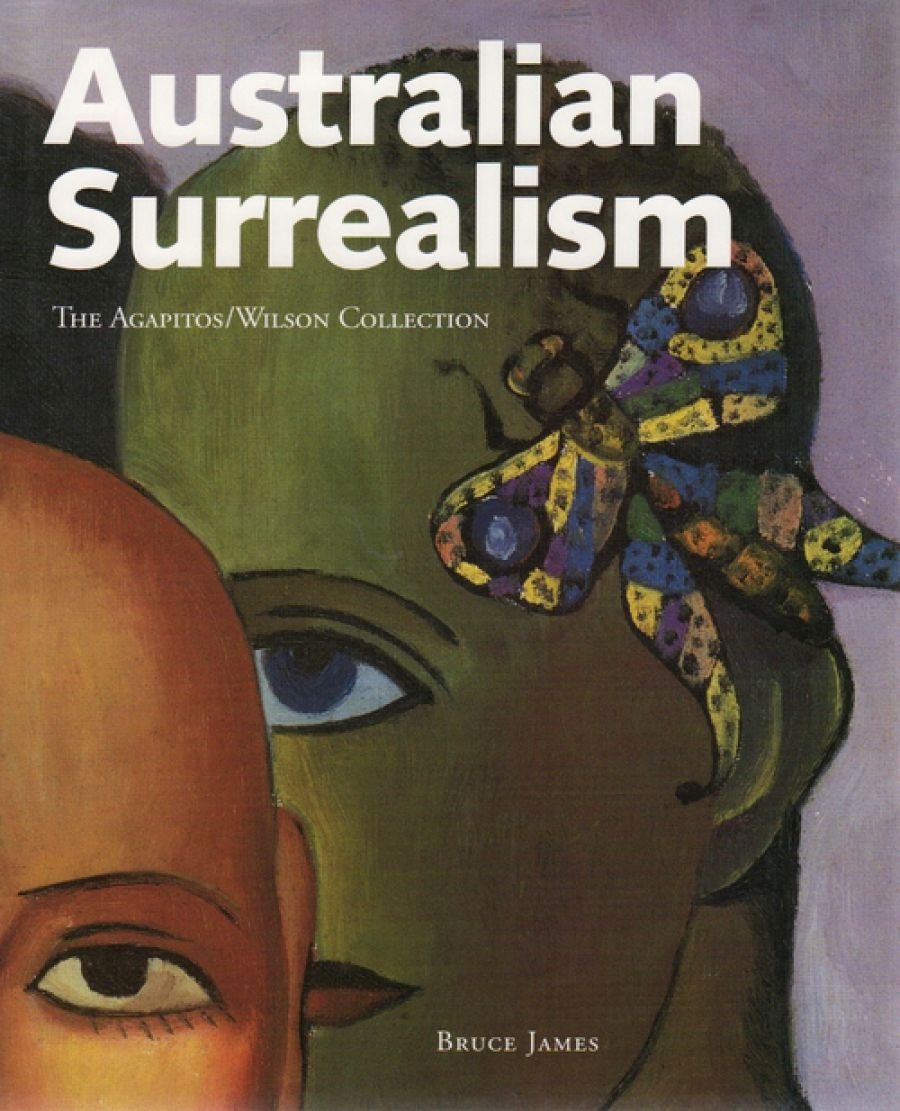

- Book 1 Title: Australian Surrealism

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Agapitos/Wilson Collection

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Surrealism had its roots in Dadaism, an accidental language – a nonsense language – and its platform, the ‘theatre of the absurd’. The repudiation of reason or rationality was precisely, it was argued, what had driven a stake through the heart of European civilisation in 1914. If the world had gone mad, then artists would give verbal and visual expression to this madness.

What had all this to do with Australia, miles from the maelstrom and still shaking its head with disapproval at the Post-Impressionists and Cubists? Surrealism proved to be a sturdy traveller and a stayer. If Europe had André Breton, Marcel Duchamp, Max Ernst and Surrealism’s most histrionic exponent, Salvador Dali, then Australia had James Gleeson.

Bruce James convinces us that, while Gleeson was its sturdiest practitioner, he was the tip of the iceberg. Surrealism in Australia touched, in passing, the works of such painters as Russell Drysdale, Albert Tucker and Sidney Nolan, and fixated a surprisingly diverse group: James Cant, Herbert McClintock (Max Ebert), Dusan Marek, Adrian Feint, Peter Purves Smith and Erik Thake, to name a few.

A fair spectrum of Surrealist imperatives found expression here: from Ebert, who said ‘I myself incline towards that aspect which expresses a free fantasy rather than a heavy concern with pathological states of mind’; to Gleeson, who wrote in his diary of the ‘the bringing together of a distortion verging on horror with a delicacy of colour … Refined destruction! Dainty Horror! A Pretty Truth!’

Drawn into Australia’s Surrealist ambit are the twisted animal carcases of the drought that Nolan was commissioned to paint in 1953, and Robert Klippel’s whimsical filaments of line and colour. There is even a work of Elwyn Lynn’s with enough oppressive imagery to make us reach for Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams.

One question remains. Would all the artists included in James’s book have recognised the Surrealist impulse in themselves, and would they have willingly attached this tag to their works, without the curatorial finger being pointed in their direction? One suspects not.

In 1937 Surrealism may have been given a boost by Robert Menzies, who launched the Royal Australian Academy of Art to defend the concerns of ‘real’ artists; that is to say, those heroes of the British eighteenth-century drawing rooms – Thomas Gainsborough and Joshua Reynolds. One of the more hilarious elements in this venture was the perceived, but flimsy, nexus of Freud’s theories of the subconscious and Surrealism (which were of growing interest to writers and artists in Australia) with Bolshevism. As many painters at this time had gravitated to the political left, along with Australian writers and assorted intellectuals, the list of miscreants Menzies wished to leave out in the cold was a lengthening one.

James’s adventure (one of writing and advising) has taken him into some esoteric corners, and his efforts are to be admired. His prose style – gyroscopic and occasionally melodramatic – seems entirely appropriate to his subject.

For Surrealists, there are stage sets, wastelands and, naturally, a few dead ends. One might quibble with some of the images (not the quality of their reproduction, which is unassailable, or the design and production of the book, which will place it amongst the most appealing offerings in recent times), but with the works themselves. There are some signally inept paintings in this collection, and their presence can only be justified by the forensic nature of the task the collectors set themselves – a virtual catalogue of Surrealist offerings in this country. Where to start? Where to stop? How far to cast the net? And what of aesthetics? Where Surrealism is concerned, like a bad dream, all aesthetic bets are off.

Aesthetics aside, this book will put to right the oversights of Gérard Durozoi’s History of the Surrealist Movement (1997), which failed to mention Australia. In 1949 even Anthony Blunt had twigged to us, saying to Bernard Smith ‘Oh,[supercilious tone] I see you even have neo-Surrealist developments in Australia.’

Comments powered by CComment