- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Film

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Ageing with Film

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

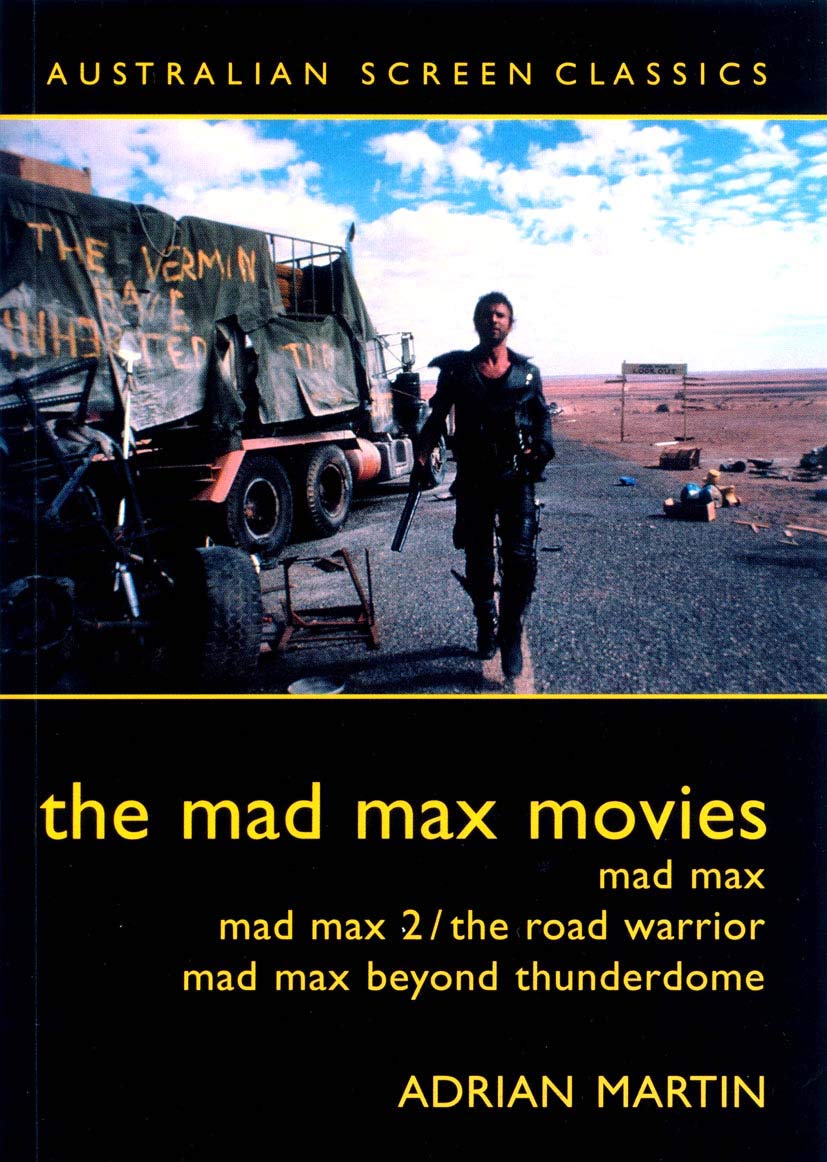

The Currency Press’s series ‘Australian Screen Classics’ is off to a good start. With playwright Louis Nowra’s Walkabout, thorough in its production, analysis and reception mode, novelist Christos Tsiolkas’s The Devil’s Playground, a study in personal enchantment, an Age film reviewer Adrian Martin’s The Mad Max Movies, an action fan’s impassioned response to the trilogy, the series makes clear that it will not be settling for a predictable template.

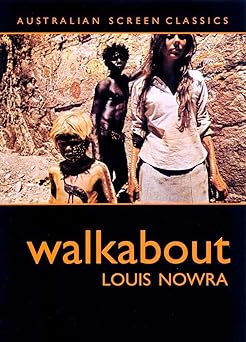

For anyone who has not seen Nicolas Roeg’s Walkabout (1971) for some years, Nowra’s study will evoke it with clarity and, because the book is also at times provocative, make another viewing essential. Nowra makes his intentions clear from the outset: he plans to trace ‘the process from the novel, to the preparation, to the filming and then, reception of the film’, and the structure of the book follows this blueprint. His admiration for the film is palpable, though this doesn’t stop him from criticising effects he finds too obvious.

- Book 1 Title: The Mad Max Movies

- Book 1 Biblio: Currency Press and ScreenSound Australia, $14.95 pb, 96 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Title: Walkabout

- Book 2 Biblio: Currency Press and ScreenSound Australia, $14.95 pb, 93 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 3 Title: The Devil's Playground

- Book 3 Biblio: Currency Press and ScreenSound Australia, $14.95 pb, 92 pp

- Book 3 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 3 Cover (800 x 1200):

Nowra’s first chapter rehearses the pre-1970s Australian film-making drought during which most of the films made were the work of overseas companies, as were Walkabout and its contemporary Wake in Fright, filmed by Canadian Ted Kotcheff. How far Walkabout is an Australian film is a matter to which he will return explicitly in Chapter 4, though the answers are being prepared for in the long preceding chapter devoted to the actual filming. The first chapter also addresses the way in which Roeg’s vision challenged stereotypical views of the outback: ‘Never before had I entertained the notion that our landscape could be so romantic, so glorious both in its potent dangers and beauty.’ By comparison with Roeg’s view of the landscape, and the place of both Aboriginal and European in it, Nowra concludes that James Vance Marshall’s novel offers ‘an Australia imagined for non-Australians by a foreigner with a few field notes at his elbow’.

The film itself is explored with an acute eye for detail, taking the reader into the heart of its strangeness as it unreels its drama of disparate ways of seeing, each precluding alter-native visions and doomed to clash. Nowra, while identifying the film’s affiliations with the ‘logic’ and brutalities of fairy stories, is nevertheless alert to moments when ‘the symbolism grates’ and to ‘clichés comparing the corruption of European civilisation to the innocence of the Noble Savage’s life’. He rightly describes this as a hard film in which to get one’s bearings, and his approach — not imposing himself on the film text, but remaining open to where exploration might take him — rewards the reader with finely sensitive accounts of cultural gulfs and their tragic potential.

Walkabout stirred controversy about its nationality when presented as a British film at Cannes Film Festival. Nowra argues that it offers a ‘critique of England’, showing ‘the British the state of their own society through the lyrical prism of outback Australia’. Not commercially very successful, it subsequently acquired a certain cult status, prefiguring developments in Roeg’s idiosyncratic oeuvre. This was his first solo feature as director; arguably, he never did anything so haunting again. Nowra puts the film before us as well as a verbal account can do, and contextualises it astutely.

Christos Tsiolkas’s The Devil’s Playground, tonally and structurally about as different from Nowra’s approach as could be, is a tender, utterly personal but still rigorous piece of critical analysis. Tsiolkas, whose novel Loaded (1995) was filmed as Head On (1998), retreads some of the same territory in this account of Fred Schepisi’s 1976 feature debut. That is, he tells us what it was like for a gay Greek boy coming to terms with his sexuality and his family’s adoptive country and culture. And how clunking that sounds compared with Tsiolkas’s evocative precision.

His take on the film is organised around three crucial viewings: when, as a boy of thirteen, he first saw it in 1978; then in 1989 when he had developed notions about film, identity and Australianness; and in 2000, when he saw the film restored in a cinema. On first viewing, he hadn’t noticed that it was set in 1953: it spoke so directly to him through its conflict between the insistent, burgeoning demands of the body and the repressive forces at work on keeping them in place. He is seduced by the film’s sexiness, its potent contrasts of light and shade, and the way in which its palette was used to articulate the conflict adumbrated above.

An apparently long digression about Schepisi’s next film, The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith, and Australian cinema, and a passionate attack on ‘dumbing down’ and cultural illiteracy, is really a preparation for his return to the film in 1989. Though his sympathy is with the film’s boy hero, Tom Allen, Tsiolkas is finely attuned to the frustrations of the lives of the Christian Brothers. He observes compassionately their constant war between the demands of the body and the world outside, on the one hand, and the constricted ambience of the brother-hood, on the other. Tom has been right, in Tsiolkas’s reading, to run away, to ‘choose freedom above faith’.

By his third viewing, Tsiolkas is ready for mature formulations about the film, about how ‘We need our national cinema so we don’t forget how and where we live’. His film culture heroes have not been the theorists who seem to him to be always too distant from the films, but the maverick James Agee and the madly opinionated Pauline Kael. Some of their acuity has rubbed off on to Tsiolkas, but what makes his book remarkable is the way he is so insistently there inside this film: he knows and responds to everything in it; he understands how seeing films at certain times can change lives, and how changed lives can subtly alter the film we keep on seeing. His touching last paragraph, following speculation about how the characters might have gone on in their lives, begins: ‘The stories in my head are not in the film; they are there because the film cannot age with me and so I age with it.’

Adrian Martin argues that, among Australian films, no others have ‘influenced world cinema and popular culture as widely and lastingly as George Miller’s Mad Max movies’ (1979, 1981, 1984). He accurately places the films in relation to other Australian films of the period (though Tim Burstall might not consider that he worked ‘predominantly in the horror-thriller forms’), accounting persuasively for the ‘instant cult appreciation’ he claims particularly for Mad Max 2.

If Tsiolkas seems to swim, perhaps a bit self-absorbed, in the current of The Devil’s Playground, Martin is like a watchful dog barking at the edges of the Mad Max movies, making excited forays at particularly choice bones. For instance, he re-creates such a key sequence as Goose’s ride and fall in Mad Max through an eighteen-shot breakdown, then stitches it together again to restore its kinetic effect to the reader. And in such rigorous analyses, of which there are several, he is alert to the contributions of not merely director George Miller but also of the editor, music director and costume designer, characterising these without losing the affective power of the sequence as a whole.

Martin contends that it is the action sequences that count (and few would quarrel with that assessment), rather than any coherence of narrative. The latter he somewhat curiously regards as a ‘literary’ quality: surely ‘coherence’ is a quality narrative may or may not possess in any narrative medium. ‘Literary’ seems to be a concept that troubles him, for else-where he considers that ‘the power and importance of Mad Max reside not in any discernible literary-type themes’ and that ‘abiding literary models of interpretation’ will get one nowhere with these films It’s not clear what these terms mean, except that they are here vaguely pejorative.

The problem with this book is, in fact, in its dealings with language. It stumbles over slackly used terms such as ‘iconic’, ‘organic’, ‘imperialist’ and others; it engages in cryptic formulations such as ‘Australia’s most completely cinematic filmmaker’; and there is too often a sense of overblown, hyperbolic usages (‘breathtaking’ is a favourite) and of a factitious vivacity, when a contemplative pause might enable important insights (and there are plenty of these) to make themselves felt.

However, he discriminates confidently among the three films, flagging the crude power of the first, what he sees as the ‘classicism’ of the second, and positing Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome as ‘George Miller’s one and only art film’. From each movie to the next, he detects ‘a quantum leap’, retaining a special affection for the first — and for the way in which special effects look like effects in that pre-digital age.

In her introduction to the ‘Australian Screen Classics’ series, editor Jane Mills stresses the importance of ‘screen culture’ in ‘stick[ing] … together’ what she sees as the ‘unruly forces’ that threaten to blur the cinema’s ‘vital role in our cultural heritage’. I’m not sure about any of this, but I do applaud her insistence that ‘Above all, screen culture is in-formed by a love of cinema’. These three books, from their divergent standpoints, evince this in spades.

Comments powered by CComment