- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

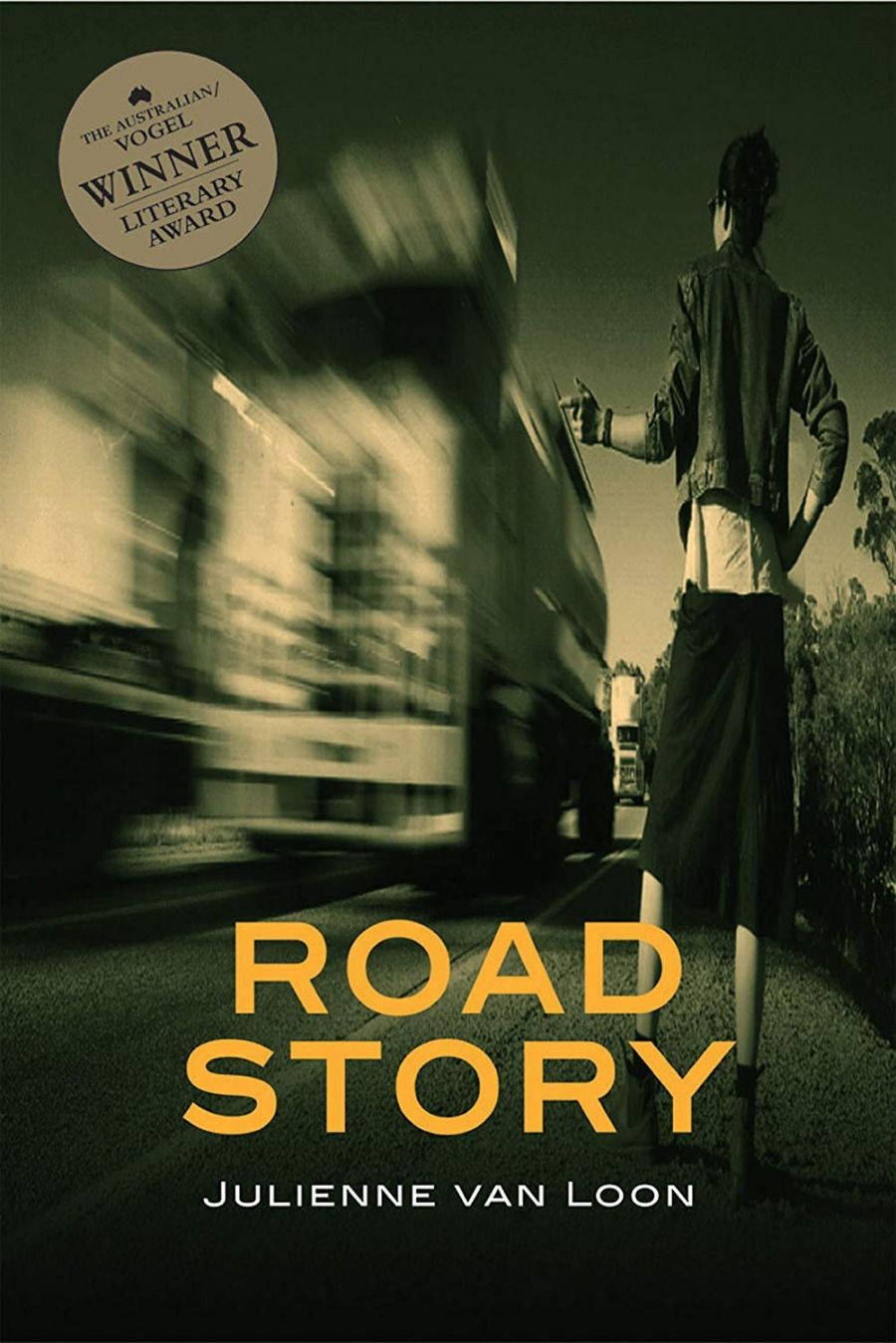

The Vogel Prize shares a reputation with the rest of the company’s products: nutritious, worthy, a little dull. But the prize’s earnest image is unfair. Any glance at the roll-call of winners over the last twenty-five years would show that the makers of soggy bread and soya cereals have done more than anyone to introduce fresh literary DNA into Australia’s tiny gene pool of published novelists. But reviewers, mostly, and the public, generally, don’t get excited when the new Vogel is published. This year they should. Julienne van Loon’s desperate joyride, Road Story, is the best Vogel winner to come along since 1990, when Gillian Mears’s The Mint Lawn, equally confident but very different, won first place.

- Book 1 Title: Road Story

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $21.95 pb, 168 pp, 1741146216

- Book 2 Title: Everyman’s Rules for Scientific Living

- Book 2 Biblio: Picador, $22 pb, 256 pp, 0330421913

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/1_Meta/November_2019/9780330421911.jpg

Van Loon gives us a story that rockets along like a vicious version of Puberty Blues, but it is written with the kind of steely control and respect for ambiguity that invites comparison with the better films of Ken Loach. All too often, novels set in rural Australia rely on pantomime flourishes that echo the kitschy fables of 1990s Australian cinema: disapproving matrons, reckless beauties, droll tradesmen. Road Story doesn’t seek to explain or to exoticise its characters; it just captures them head on. When the roadhouse’s battling owner Bob tells a hoary blue joke, ‘the drivers laugh with detachment, jiggling their bellies a little, or smirking sideways as they inhale on their ciggies. One of them gives off a shrill, wheezy chuckle that sounds like a diesel engine not quite firing. Diana doesn’t have the energy to laugh, but she feigns a smile. Somehow it feels safer to smile.’

Diana is a prickly woman, and, in short flashbacks that don’t overdo the exposition, we begin to understand why: the drunken mother, the many schools, the decision (aged fourteen) to bolt to the coast with her wild girlfriend Nicole. Van Loon explores the dynamics of this desperate friend- ship with sensitivity and daring. There’s a scene where the two girls, working on a fishing trawler off the coast of Ulladulla, dare each other to play along with a sexually charged card game that threatens to turn into a gangbang. Van Loon is also taking a risky gamble here, but she pulls it off. The tension never really slackens, even if Diana is allowed a couple of juicy sex scenes with a young trucker and a night at the rodeo. It doesn’t take much to make the reader uneasy. At night, rabbits edge towards a patch of grass under a leaky tap. A trucker’s hands shake violently from the effect of uppers. Diana stacks the fridge and thinks back to the girl in the car. ‘She is going to fit as many cans on the one shelf as is physically possible. “Dead, alive, dead, alive, dead, alive.” She tries to fit the very last can (“dead”) on the shelf with the others, but can’t.’

Dr Alfred Vogel might have enjoyed Carrie Tiffany’s début, Everyman’s Rules for Scientific Living, although it isn’t one of his prizewinners. The Swiss nutritionist, who published his own guides for better living, might have warmed to Tiffany’s awkward hero, Robert Pettergree, an agronomist determined to follow evidence-based scientific practice in every area of his life.

Summaries of Tiffany’s genuinely charming novel may trigger red flags for the wary reader: the storyline skates so very close to those damn rural fables mentioned earlier. It has even got one of those dressmakers that have plagued the collective literary consciousness for the last decade. But Tiffany is clever enough to incorporate these elements into her story without turning it into a cartoon. Most of the time, anyway.

In Tiffany’s enjoyable outback romance, we first meet Pettergree on the ‘Better Farming Train’, a locomotive government campaign bringing scientific enlightenment to rural Australia. Our narrator is Jean Finnegan, the seamstress from the women’s carriage who is attracted to both Pettergree and the shy Japanese chicken-sexer Mr Ohno. Both Pettergree and Finnegan suffer from unfortunate childhood flashbacks that Explain Much About Their Character, but these pass quickly and do not recur. The novel has many incidental pleasures, including black-and-white photographs: the nests of Mallee fowl, a plump ginger moggy, a sturdy blonde toddler, all slipped into the text as if pasted between a scrap book’s pages.

Tiffany is a comic writer with a delicate touch. On the Better Farming Train, beasts and experts are all on display. We meet the folly cow, a rangy scrub beast that serves as a contrast to the breeds the government prefers. There’s Sister Crock, an unsmiling supernanny determined to bring domestic sciences to the wretched women of the wheatlands. Even Pettergree is on show after-hours as a man who can tell where a soil sample comes from just by tasting it. In one of the sweeter scenes, he teaches Jean the principles of experimentation by testing if she really can taste if someone’s added the milk before they pour the tea.

The second half of the book takes place on Pettergree’s model farm, staked out, in calculated defiance of the odds, in the salt-scrub of the Mallee. I spent my early childhood there, and many of Tiffany’s details echo my own faded memories: children smashing mice on the ground during a plague or running out to dance during a rare sunshower; or flies thumping angrily against window panes and dirty orange clouds rolling across the afternoons.

The fierce sexual attraction between stuffy Pettergree and his lively bride is nicely realised, especially when they first have sex in the dark, moist apiary carriage of the train, surrounded by smoke-doped bees. They’re still at it like rabbits on the farm, but they’re also into more sober experimentation, baking test loaves to assess the annual wheat harvest.

The novel’s thematic parameters widen dramatically on that Mallee farm, as Tiffany plays with the perennial dramas of the man on the land. Pettergree is just one in a long line of proselytisers who believes they could turn the desert into a garden, if only farmers used superphosphate, or ploughed the correct furrows, or bred the right strain of wheat. But in the auctions and arguments, Tiffany shows how hope erodes, slower than topsoil, but just as surely.

Meanwhile, I can only feel optimistic. The Australian fiction crop has produced a thin harvest over the last few years, but this year we are seeing some really impressive yields, especially from débuts. To read two terrific first novels for one review feels little short of miraculous.

I can’t prove it empirically, but my gut feeling is that the Oz Lit crop of 2005 will be just fine.

Comments powered by CComment