- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Society

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

If it is the case that we can no longer avoid the effects of living under conditions of globalisation, then increasingly that spatial dimension governs our lives. Look not, therefore, deep into the history of our individual nations or localities to explain what is going on, but lift your eyes to the horizon, and beyond, where a devastated city may be smouldering. Within minutes, a local politician will be warning us that we may be next.

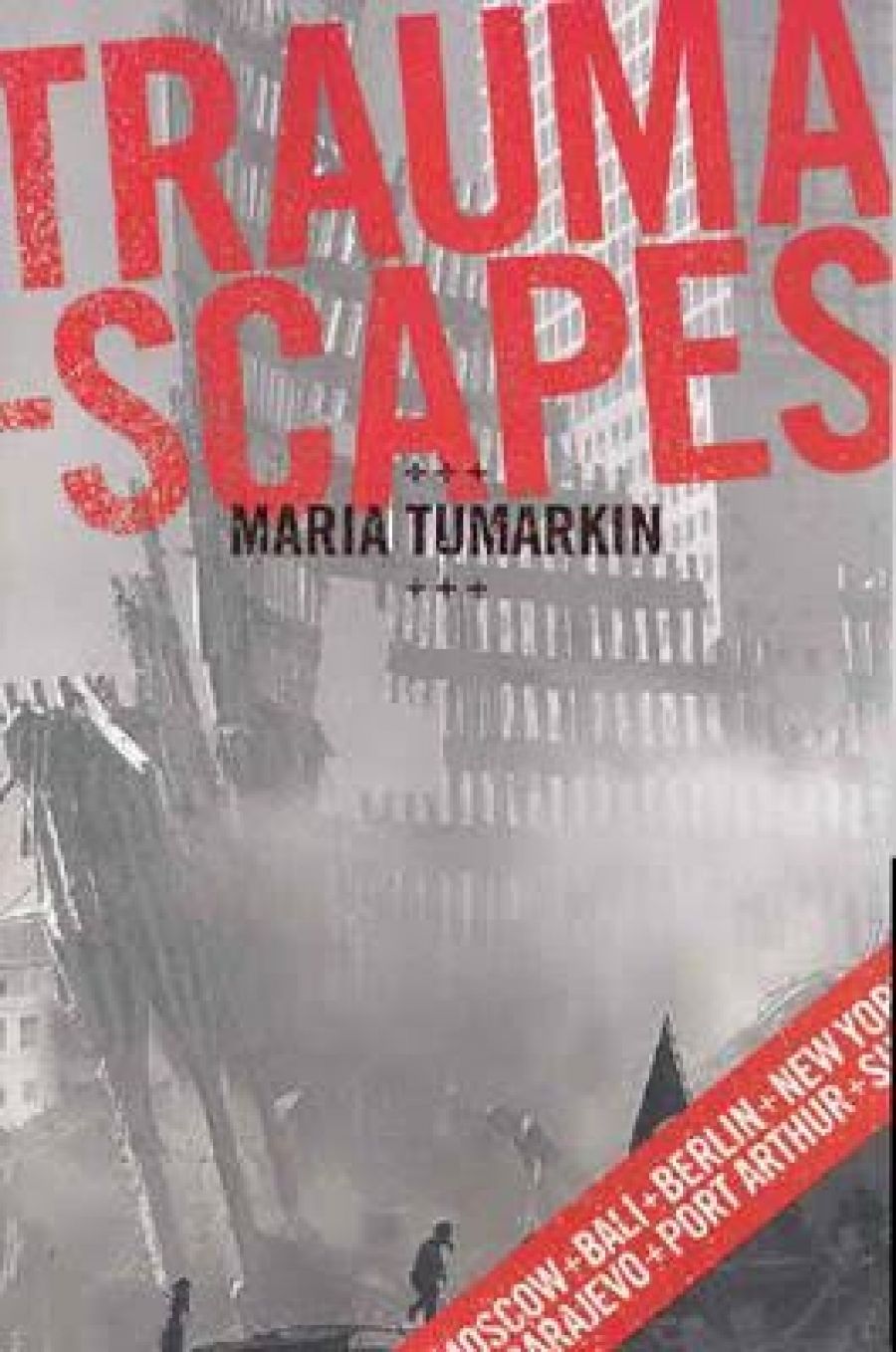

- Book 1 Title: Traumascapes

- Book 1 Subtitle: The power and fate of places transformed by tragedy

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne University Press, $34.95 pb, 279 pp, 0522851770

Sarajevo was besieged between 1992 and 1996 by Bosnian Serb forces determined to ethnically cleanse this beautiful multicultural city. The courage and solidarity of the Sarajevans is documented in detail here. A few months later, Martin Bryant shot thirty-five people at Port Arthur: Australia’s worst massacre by an individual, at our most notorious convict site. The historical resonances ran deep, transforming a premier picturesque site into a ‘dark tourism’ attraction.

While Tumarkin does discuss New York’s Ground Zero, the US site she chose to visit was Shanksville, the tiny town in rural Pennsylvania where United Flight 93 was put down, probably by the passengers who are now the heroes of 9/11. Unlike Ground Zero, where George W. Bush mounted the rubble with a megaphone to launch his terror-inspired presidency, Shanksville is remote and unspectacular, yet it attracts hundreds of thousands of tourists.

Bali, where eighty-eight out of the two hundred killed by Jemmaah Islamiah were Australians partying in the two clubs at Kuta Beach, is the closest the so-called ‘war on terror’ has got to Australia. What the aftermath of this event brings out most strongly is the cultural differences between the Hindu Balinese and the Westerners, each with their own ideas about how the sites should be remembered. Moscow, finally, in Tumarkin’s country of origin, was where Chechen terrorists held hostage the audience in a popular musical theatre, in October 2002. One hundred and twenty-nine innocent people lost their lives during the siege and the bungled rescue attempt.

As she was going about researching this book, Tumarkin found that ‘people would instantly support my attempts to connect things’. So while the events were not all of the same type or scale, she thought that ‘to write, case study by case study, of suffering and trauma [would be] a way of deepening despair and reinforcing isolation’. She goes on: ‘It is only in connections and resonances between places, histories and experiences that we can recognise that life is not irreversibly ruptured by suffering …’ This way of writing trauma with a spatial method carries through into the formal structure of the book. There are three major parts: ‘Going to Ground’, about the urge to make the pilgrimage; ‘Face to Face with a Traumascape’, about living through the events; and ‘The Fate of Traumascapes’, dealing with aftershocks and memory. This layering structure, visiting all six places in different sections, has the effect of creating the connections she wanted and avoiding the obsessive impacting effect that would have resulted if she had dealt with each in turn.

Speaking of each in turn, that individualisation is precisely how the main method of dealing with trauma – psychological counselling – works. I’m no expert, but I think trauma counselling is a one-on-one activity, with psychologist and ‘patient’ working through a predetermined method. Already the tendency to pathologise the individual is there, leading eventually to the administration of anti-depressants.

In a clear exposition of the meaning of the term trauma, Tumarkin creates a space for her collective and spatial configuration of the concept, and this involves some critique of the tendency to isolate and medicalise. Precisely because she wants to deal with ‘shared human suffering’, she has to point out the limitations of the psychological vocabulary. Indeed, the administration of that expertise is hardly one that all countries can afford, nor is it in any way linked to the social and political causes that can give rise to catastrophic events.

So it is not the ill-used concept of political terror that links Port Arthur to Bali; nor are the agents the same. But the experience of the places as traumascapes has something crucial in common, the complex set of feelings and ritualised practices that evolve in an uncanny way among people who visit them, and the same happens to people who can’t get overwhelming events out of their heads: ‘Traumatised people,’ says Tumarkin, ‘do not experience time as linear … [they] have to live with the past that refuses to go away … The past … enters the present as an intruder.’

Tumarkin is well aware of Australia’s extensive traumascape of Aboriginal massacre and oppression, but does not go into the processes of its attempted erasure. Sun-seeking tourists on Rottnest Island, for instance, do not have their tranquillity disturbed by any signs indicating the place was a gulag for Aboriginal prisoners. But collective memory is a persistent thing, and collective remembrance may be a way of healing the ‘scar tissue’ of the world. Maria Tumarkin’s contribution to the understanding of this contemporary phenomenon is outstandingly original and rewarding.

Comments powered by CComment