- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Most of a lifetime ago, I read of an exhibit at the Bell Telephone headquarters. It consisted of a box from which, at the turning of a switch, a hand emerged. The hand turned off the switch and returned to its box. If this struck me as sinister, it was because the gambit seemed emblematic of human perversity – of a proneness to self-annulment ...

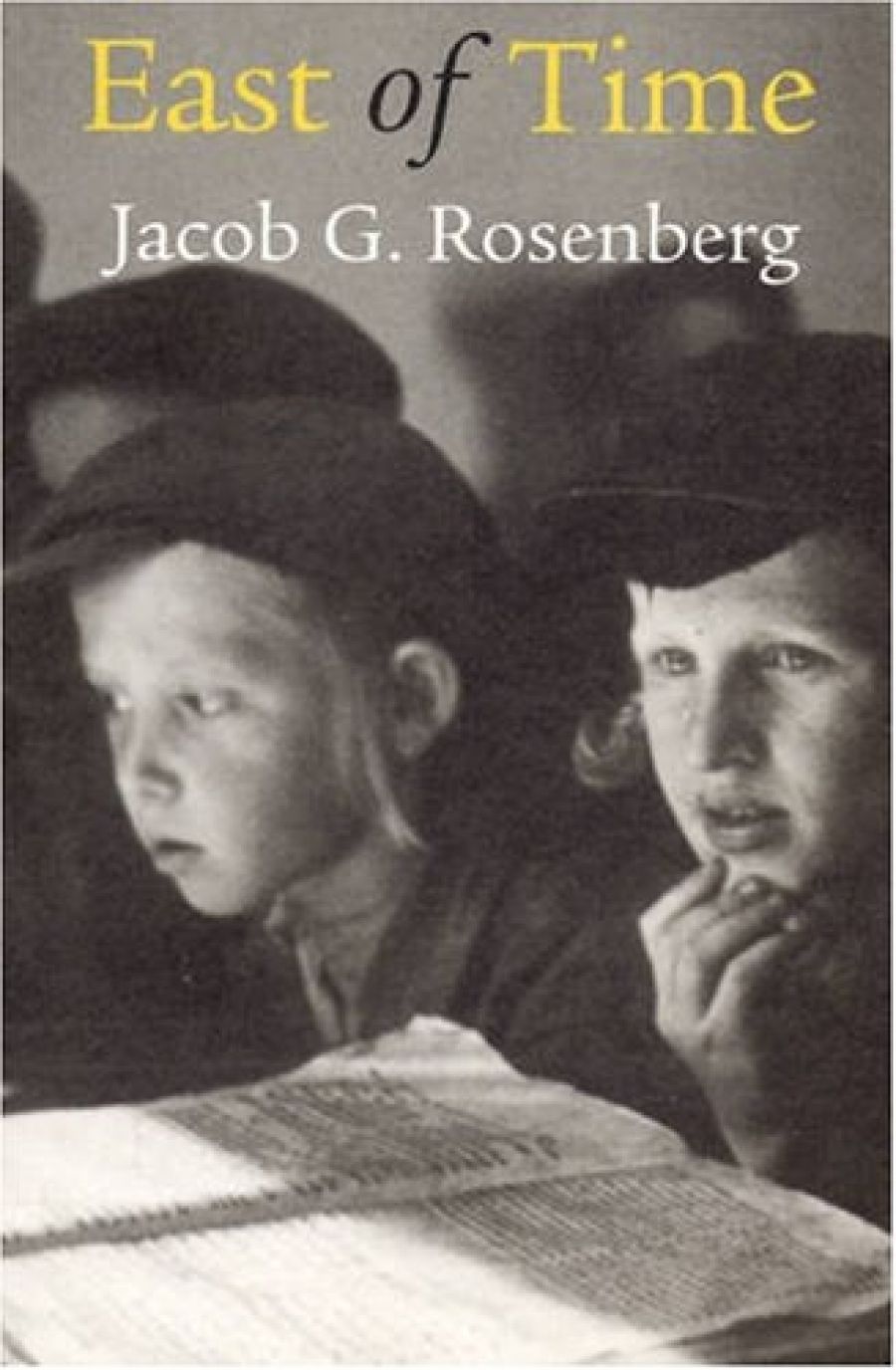

- Book 1 Title: East of Time

- Book 1 Biblio: Brandl & Schlesinger, $26.95 pb, 220 pp, 1876040661

One of its tasks is to do justice both to life’s plenitude and to its privations. So Rosenberg can write:

My neighbourhood had good reason to be proud. Though famous for its poverty, it was inhabited by hundreds of gifted artists, singers, musicians and thinkers who had never had the chance to display their skills, along with scores of religious and secular messianic redeemers. I lived in the heart of an iridescent kaleidoscope, a veritable bazaar of diverse people and ideas – the kind of place you would expect to experience only in a storybook. A local wit put it another way: out of the nine thousand denizens of our precinct, at least ten thousand were poets.

He can also write: ‘We arrived at our destination on a hot August day of barking dogs. There, beneath an unblemished sky, dressed in black and with gloves of white, stood a man called Mengele who was convinced that he was God’s deputy.’ We are indeed back with the poet, a cherisher of life’s possibilities and of the verbal resources for their naming: and also with the poet who knows how much may be delivered by understatement, by the organisation of the unsaid. In fact, the first of these passages occurs more than halfway through the book, and the second passage near its beginning: but East of Time turns its meditative wheel through the desperate and the endowed alike, garnering what is indeed available, and incising what has been lost.

‘Jews,’ Rosenberg says, ‘are forever carrying on a love-affair with hope – if there were an Olympiad of hoping, my people would invariably take out all the gold. Consequently, we quickly become accustomed to our permanently ephemeral existence.’ His book is of such a temper that reflections of this kind seem natural – experience crystal- lising into insight – but I have no sense that Rosenberg needs recourse to generalisation as a shelter from the intolerable. He has something of an aphorist’s flair, but here aphorism is a way of drilling deeper rather than a way of stepping back. I was from time to time reminded, while reading this book, of the mentality of Czeslaw Milosz, another émigré, in different circumstances, from Poland. For both men, whether it is a matter of poetry or of prose, language is a distillation rather than an effusion, and the pressure of event tells.

What I have said so far might suggest that East of Time is the work of a natural solitary, a consulter by instinct of personal sensibility as warrant for the writing: but, apart from the degree to which that must always be the case when reflection is at issue, it is not the truth at all. The preface, once again, says that the book ‘is a rendezvous of history and imagination, of realities and dreams, of hopes and disenchantments’: and the participants in that rendezvous are the young and the old, the familiar and the alien, the donors of love and the votaries of death. Perhaps it is true that any thoughtfully conceived memoir will be testing the terms on which we choose, or are constrained, to live together as human beings, and certainly that is true of this book. Rosenberg writes with a blend of acuity, ruefulness, tenderness and stark-eyed appraisal of those who have come his way and who have, for good or ill, attempted to take him along their ways.

‘Sometimes’, he says, ‘hope can be strongest when lying on its deathbed’, which I take to be a saying as hard-won as it is challenging: one does not easily take issue with a refugee from hell. And indeed, whether writing to report first-hand experience or to relay that of another, Rosenberg goes on testing the terms of hope, and its nearness to the deathbed. He tells of a man, about to be hanged by the men in black, who asks to touch the officer in charge, ‘to ascertain if this man, too, has been created in God’s image’. The book can give no answer: but it is haunted by the question.

Comments powered by CComment