- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Custom Article Title: David McCooey reviews 'Hoi Polloi' by Craig Sherborne

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

A laughing man, according to Flaubert, is stronger than a suffering one. But as Craig Sherborne’s extraordinary new memoir of childhood and youth shows, the distinction isn’t that simple. There is much to laugh at in Hoi Polloi, but this is also a book suffused with pain and suffering ...

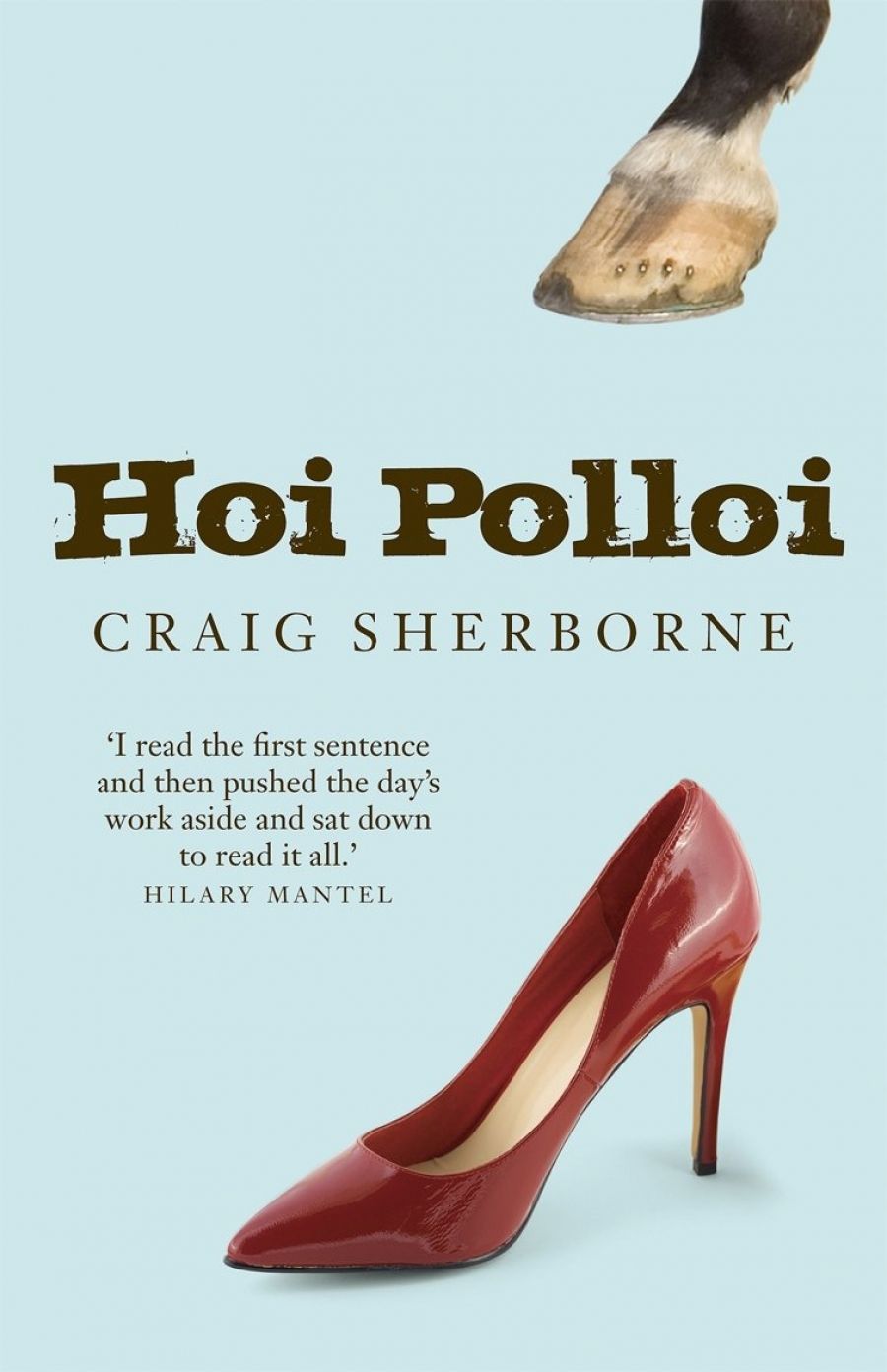

- Book 1 Title: Hoi Polloi

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $27.95 pb, 197 pp, 1863952217

This is all the more noteworthy given that the events of this narrative are outwardly undramatic: the family returns to the author’s birthplace, Sydney (‘of course, my son was born in Sydney,’ the narrator’s mother likes to tell the provincial New Zealanders); the narrator undergoes a religious phase; the narrator’s father buys a race horse; the family begins to frequent the racing world; the narrator attends a private school; and the narrator has a number of sexual experiences. But it is the treatment of these events that make this work so extraordinary.

The world depicted in Hoi Polloi is an extreme one. The l960s are far from swinging, and the 1970s not really super. Indeed, the book hardly seems to inhabit these decades as we conventionally think of them. This is one of the book’s strengths. It presents the past as radically different from the present, as a world that requires more than clichés for us to be able to inhabit it imaginatively. Sherborne’s imaginative inhabitation of these times and places is strikingly negative. Australia and New Zealand are places rent by classism, sexism, sectarianism, bigotry, and more physical forms of violence. Both places are defined especially by racism. Maoris, for instance, are called ‘horis’ by the white population, and the narrator struggles to match his experiences with the models of race presented to him by adults. The narrator’s parents are the key adults here as elsewhere, and they are presented with a deeply satirical approach. The father is referred to as ‘Winks’, the mother as ‘Heels’. The mother, in particular, is concerned with the niceties of class, with the need to be ‘nice’.

Language is important in this regard. As per the ‘hotel’, the family lives in an ‘apartment’, not a ‘flat’. Appearances count. The narrator’s mother ‘know what’s in and what’s out. In for a lady is to have your hair swept up, the whole works, into a bun and tinted peach or apricot and sprayed stiff till it’s 100 per cent wind-proof.’ As the reference to ‘the whole works’ shows, Sherborne is attuned to the linguistic markers of character and class.

In this respect, and in the generally satirical tone of his work, Sherborne could be seen as working in the tradition of Barry Humphries or Clive James. But Sherborne is, if anything, more of a stylist than these two. A more accurate antecedent is that stylist of stylists and hater of bourgeois provincialism, Gustave Flaubert. The technique pioneered by Flaubert known as ‘free indirect discourse’ (in which the views and language of characters are presented ironically through the narrator’s voice) is one of the key techniques used by Sherborne. And like Flaubert, Sherborne is sensitive to the hypocrisies of class and the self-serving way in which people can engage our emotions and sympathy. (One thinks here of the narrator being told untruthfully that his father has a heart condition and only five years to live.) Like Flaubert, Sherborne is a master of sliding from the tragic into the farcical. This is seen in a set piece in which a drunken Maori is apparently killed by Winks. When the narrator’s parents debate what to do (tell the police that the man was a robber? that he tripped?), they find that the man has disappeared. The episode degenerates into farce when the Sherbornes discover that the man is alive and urinating nearby, allowing Sherborne to show his skill in delivering punch lines.

But while the comedy is real, so is the suffering. Understanding of suffering comes from the sensitivity of the narrator, a shy only child with a stutter (magically cured by a blow to the head), who witnesses numerous violent and shameful events. These range from drunken violence in the hotel, to violent schoolboy ‘pranks’, to the way horses are treated on the race track, to the absurdly tragic death of a boy who falls off a cliff while running after his dog (which was running after a ball).

Sherborne avoids presenting his younger self as merely an innocent by showing his passivity in the face of things he knows he should respond to. A recurring figure is the narrator’s inability to act. He is unable to stop his father from being attacked, unable to reciprocate fully in sexual encounters, unable to stop his peers from abusing a drunk man lying in a street (in a scene reminiscent of A Clockwork Orange) and so on. The narrator is also far from innocent when it comes to his own emotional hypocrisy. A key moment in Hoi Polloi is when the narrator pretends to be paralysed after receiving a beating from his father.

As such episodes suggest, this is an uncompromising work. It is darkly hilarious, a condition that is also related to the narrator’s parents. Faced with a crying woman at a party, the narrator’s mother asks the woman to tell everyone what is upsetting her: ‘“Tell us about it by all means,” Heels reassures her half-heartedly. “You’re among friends. I’m sure there’s a laugh in the story somewhere.”’ This is the tonic note of the work as a whole. There are laughs found in the most singularly unexpected of places.

This is probably because the narrator, like the author, is so singular a figure. He stands apart from others and observes life with a preternatural intensity (seen, for instance, in the way he describes a baptism). This singularity stems from the narrator’s position of not fully belonging. As a sensitive only child to unsympathetic parents, and as a member of a private school whose class pretensions he can’t aspire to, the narrator stands alone. The issue of class, as the title of the work suggests, is a defining feature of identity. The narrator’s mother uses the term ‘hoi polloi’ incorrectly, thinking that it refers to the upper crust rather than to the general mass of people. Caught between these two meanings of the word, Sherborne belongs to neither world. From this outsider position, he has fashioned a unique vision. He looks from the bend in the stairs in horror and amusement at what the hoi polloi enact, indifferent to – or ignorant of – his presence. Hoi Polloi is a brilliant, searing memoir and a major new work of life writing. It is both brutal and tender, and it reveals, as Flaubert might have said, the grotesque and the tragic that cover the empty longing of life.

Comments powered by CComment