- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Contemporary Australian fiction continues to lean on the national past. Perhaps that’s a comment on the present, or the future, for that matter. It seems to be not so much a matter of the past being experientially ‘another country’, but a more engaging version of the literal one ...

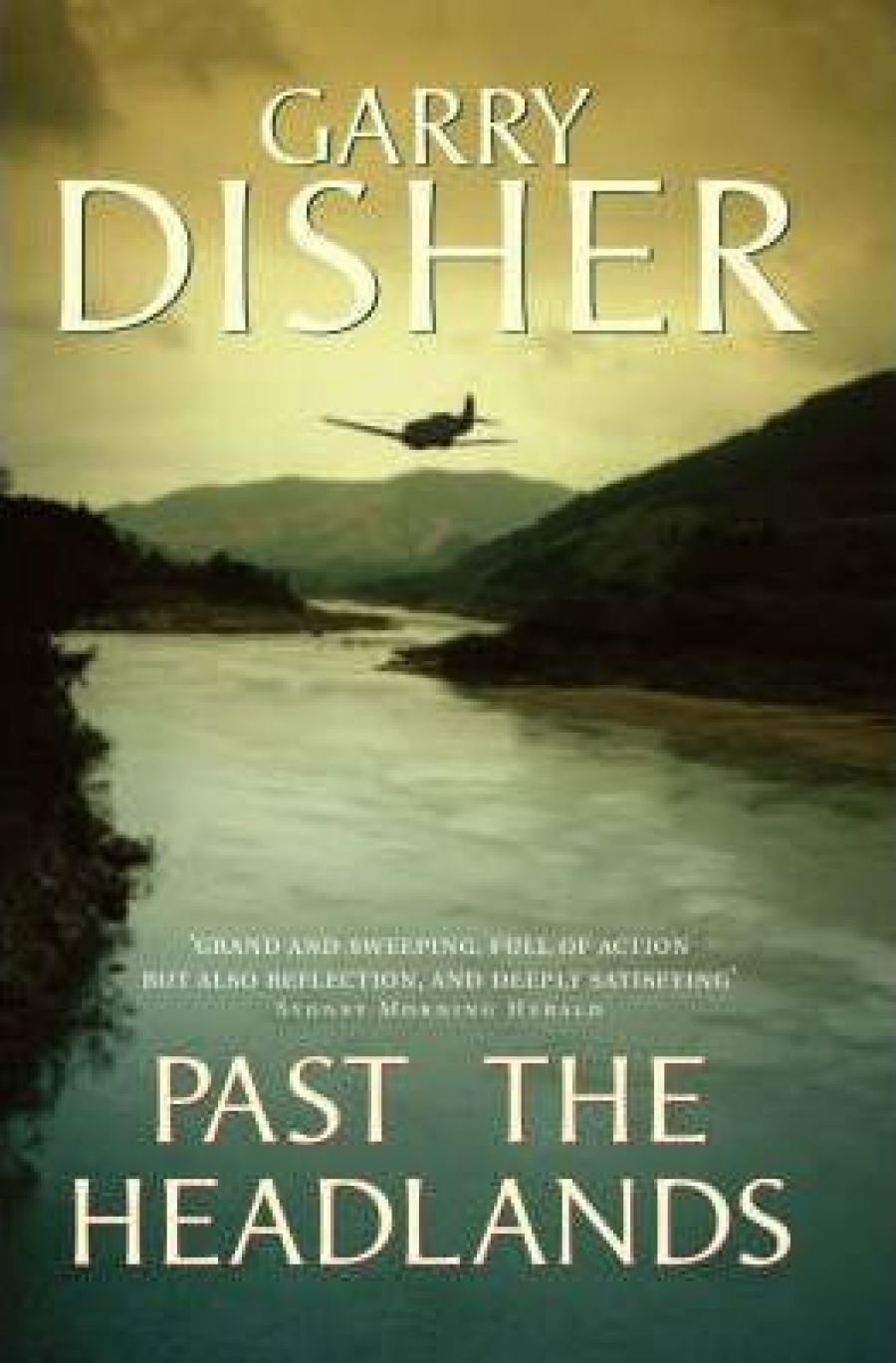

- Book 1 Title: Past the Headlands

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $24.95 pb, 352 pp, 1865085391

But the Japanese are not his only enemy. In a Singapore morally, militarily, and in every other way collapsing before the advancing Japanese, Quiller becomes entangled in the machinations of his craven cousin Cameron, one of the all-time great bastards of Australian war fiction. Meanwhile, back at the ranch in Western Australia, Cameron’s wife, Jeannie, is forced to accommodate more war refugees washed up on Australia’s shores than Philip Ruddock could poke a stick at. This is a self-consciously ‘big’ novel, a Kiplingesque saga of war and spying across frontiers, of cultural allegiance and exile, human treachery and loyalty.

Garry Disher is a versatile novelist. He has just about written it all, from bracingly bloody (and utterly contemporary) crime fiction, to children’s literature. But in Past the Headlands he may have overreached. This is more a matter of style than structure, for the novel is expertly plotted. This reader, at least, found the book overly, and sometimes redundantly, descriptive. In Malaya, Quiller comes across a local girl described as ‘small, shy, vividly smiling’ – can one be both shy and vividly smiling? Later, in a Sumatran warehouse, an exhausted Quiller, ‘racked’ by yawns, beds down for the night, which does not stop him identifying floors and walls ‘redolent of rubber, fish and rotted food, old colonial odours caught forever and baked every day in airless heat’. Moreover, clichés abound. An English spy utters things like ‘I say, steady on’ and ‘pull yourself together, man’, and letters home are edited by ‘the censor’s heavy hand’.

Colonial Singapore is given the full Orientalist treatment – a pungent (you can smell it before you see it, ‘even in an aeroplane’) seething mess of humanity, ‘trading, praying, cooking, eating, socialising, voiding their wastes’. Why is it that only the Asian characters in Western fiction set in ‘the East’ do number twos? The city is also dangerous and (naturally) sexy. Quiller feels his ‘sexual longing’ stirring ‘like a bear coming out of hibernation’, a strange metaphor to apply to tropical Singapore. After an aborted relationship with an amiable but determinedly virginal Australian nurse called Dorothy Barrowman, Quiller flourishes under the practised hands of Lee Lin, the proverbial Oriental whore with a Heart of Gold. But other than the woman he ends up with – I won’t spoil it by letting on – Quiller’s most important female relationship is with a young English orphan called Maisie, whom he first encounters during his escape-by-sea from the fallen city. ‘I want you to be my Dad’, she tells him later.

But in Neil Quiller, Disher has created an undeniably compelling and complex character. Quiller’s indefatigable decency contrasts sharply with the general run of demoralised Australian soldiers in the book, who are racist and gutless almost to a man. So much for the national myth of our betrayal at Singapore by the self-interested, weak-kneed Poms. The sauve qui peut in the face of the Japanese advance provides a welcome corrective to the sentimental picture of Australian soldiery so common in retrospective war fiction. Finally, it might be said of Past the Headlands that it fulfils two of the major functions of any narrative. It inhabits a believable imagined world, and it makes you want to read on. It may end up ranking with A Town Like Alice and My Brother Jack as one of the great Australian fictional melodramas of love, war and divided allegiance. We await the television mini-series.

Comments powered by CComment